[et_pb_section bb_built=”1″ admin_label=”section”][et_pb_row admin_label=”Row”][et_pb_column type=”1_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

The final part of our story of cycling’s influence on Spanish culture by Mark Johnson and James Stout…

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][et_pb_column type=”3_4″][et_pb_text admin_label=”Text” background_layout=”light” text_orientation=”left” use_border_color=”off” border_color=”#ffffff” border_style=”solid”]

How bike races were used as a political tool in a time of dramatic change.

(A flashback to RIDE #46, published October 2009.)

• Part 01 • Part 02 • Part 03 •

Volta a Catalunya – Age, beauty & politics

Only the Tour de France and Giro d’Italia predate the Volta a Catalunya. The week-long stage race was founded in 1911 and takes place in the fiercely independent Catalan region of north-eastern Spain, an area bounded by the Pyrenees to the north and the Mediterranean Sea to the east.

The first Volta a Catalunya was a three-day affair in January 1911 designed to rally disparate social classes behind the idea of Catalan nationhood.

Its route was mapped to geographically delineate the boundaries and features of Catalonia – that is, inscribe where Catalonia ends and Spain begins.

Beginning in 1922 the race was supported by the Unió Esportiva de Sants, a social and sporting club funded by Catalan unions in a working-class Barcelona neighbourhood. The club brought together cycling and football aficionados from the many factories that made Catalonia one of the most economically vibrant regions of Spain.

The combination of this working-class organisation and patronal sponsorship shows that the Volta was born as more than a bike race; it was (and remains) social and nationalistic glue meant to unite classes behind the idea of a single Catalan national identity.

Catalonia had been distinct from Spain for centuries, with its own language and a vibrant culture centred in Barcelona.

Although the region possesses its own renowned architecture (Antonio Gaudi’s famous Pedrera and Sagrada Familia are both in the city) and art (Picasso spent his early years in Catalonia), at the turn of the 20th century Catalan identity had failed to permeate the working classes.

This was largely due to the fact that many were immigrants from the less developed areas of Spain, often pejoratively called xarnegos. They felt stronger connections with the places they came from than Catalonia, which was often adopted out of economic necessity rather than personal or cultural affinity.

It had always been an aim of Catalan nationalists to create a cross-class national alliance that would grant their cause deeper, presumably more durable support. They found associational activity to be the best way to incorporate all the people of Catalonia into the Catalan nationalist ideology.

In the early 1900s the Volta provided an opportunity to unite capital and labour behind a nationalist project.

Because hard bike racing summarily ejects riders lacking perseverance, discipline and focus, the sport had appeal to Catalans. This industrial, scientific part of Iberia has long prided itself for its work ethic and seny (common sense), which Catalans feel distinguishes them from, in the Catalan point of view, the lazy and impulsive Spaniards lounging away to the south.

By the Spanish Civil War cross-class Catalan nationalism had begun to take hold. Mariano Cañardo placed second at the 1935 Vuelta a España. Before this he was already a Catalan cycling star.

After suffering a knee injury in the 1932 Volta he soldiered on for days in excruciating pain. When he could no longer continue, he wrote a letter to the people of Catalonia explaining his decision and apologising for letting them down.

After placing second to Belgian Gustaaf Deloor in the first edition of the Vuelta, Cañardo was presented with a trophy for being the first Spanish finisher. Cañardo promptly delivered the trophy to Lluís Companys, the president of Catalonia who had been jailed by the Second Republic for leading an uprising and declaring a free Catalonia. (Companys was ultimately executed in 1940 atop Barcelona’s Montjuic, some 500 metres from where Thor Hushovd took stage six of the 2009 Tour de France.)

Cañardo’s jail visit was politically loaded and multiplied the Volta’s already portentous nationalistic significance.

The Second Republic had violently put down an early attempt by Companys to foment a separatist revolt, and the skittish young Spanish government was anything but open to his ideas or those who supported them.

Visitors to the Olympic museum in Barcelona today will see a tribute to Cañardo – who eventually won seven editions of the Volta.

Along with his 1935 Vuelta bike and the trophy he presented to Companys is a book he received in return which bears the dedication: “To my friend and great sportsman, from between bars. Luis Companys”.

Under Franco, Catalonia’s Volta implicitly rejected the national identity constructed by the dictator and communicated through the Vuelta. Often the parcours included sites that were pillars of the Catalan sense of self, such as the Montserrat monastery, a significant religious retreat and home to monks who sheltered Catalan dissidents.

By routing the course to historic sites, Catalonia’s regional race perpetuated the idea of a distinct Catalan history quite apart from the rest of Spain.

The Volta also helped followers imagine themselves as part of a larger Catalan community.

Even the most remote Catalan villages participated in the Volta; when it passed through their village citizens could step outside and become part of the moving spectacle.

They would then return to the bars and cafes to listen to radio broadcasts and read newspaper reports of other citizens sharing the same festival of cycling elsewhere in the nation. In other words, the Tour of Catalonia helped foster a concrete sense of a shared, common community in the minds of all who witnessed it, no matter how disinterestedly.

As Tour de France director Jean Marie Leblanc once noted of his big race, “The Tour is social cement.”

With loyal supporters following via newspaper and radio reports at home, Catalan riders had always performed well at an international level. But it was not until Catalan José Pesarrodona took a Vuelta victory as part of the KAS team in 1976 that Catalans had a victor in Spain’s national tour.

As in 1977, the 1976 Vuelta was riven by protests and violence in the Basque country. Illustrating their prized characteristics of common sense and measured judgement, the Catalans walked away with the Vuelta while the Basques were busy burning buses or, in the case of Spanish strongman and 1970 Tour de France victor Luis Ocaña, losing the Vuelta by forgetting to eat properly. Showing the Catalan’s proud tradition of using quiet persistency and good sense over explosive shows of emotional strength, Pesarrodona won the 1976 Vuelta title without taking a single stage.

After the transition to modern democratic Spain, the Volta a Catalunya was one way Catalans were able to uncork the free public expression and perpetuation of their suppressed Catalan nationality – a passionate exhibition through cycling that endures a century after the race was founded.

* * * * *

Spain’s Sporting Siglo de Oro

The Spanish traditions of using national tours to reinforce national character underpin Spain’s current ascension as one of the preeminent players in world sport.

In 1985 Spain signed a Treaty of Accession with the European Union. This marked a formal entrance into the European community, and a symbolic ending of the popular notion that Europe stops at the Pyrenees.

Spain had overcome fascism and a failed coup d’état in 1981, asserted a commitment to democracy and been accepted into modern Europe. A concerted global marketing effort made Spain a wildly popular tourist destination for travellers from throughout Europe and the rest of the world – visitors who today spend over 100 million euros annually in Spain.

For the first time in years one could be proud to be a Spaniard.

At the same time new stars entered cycling in the form of stick-thin Lejarreta, 1988 Tour de France winner Pedro Delgado and five-time Tour champion Miguel Indurain.

Affectionately known as ‘Perico’, Delgado was the first star of the new Spain. He is also the forefather of Spain’s current sporting golden age. Up until this time Spanish cyclists had a deserved reputation for racing as lone wolves who worked for individual glory, but rarely rode in concert with team-mates.

Delgado tacked away from this anarchic racing style and approached his sport with scientific methodology. As a result of a more formulaic approach to training, Delgado prospered in the time trials, a skill which had thus far eluded his compatriots but would characterise Miguel Indurain’s prime years.

Only 16 years old when Franco died, Perico was neither tainted by franquismo nor by regionalist violence. In the 1980s Delgado – more than Real Madrid or FC Barcelona – came to represent the sporting renaissance Spain enjoyed as it cast off the shackles of dictatorship and low self-esteem.

At the 1985 Vuelta, thanks to a stunningly remarkable instance of cross-Spanish team national alliances, a rival Spanish team, Zor-Gemeaz, sacrificed its excellent chance of putting its Colombian rider Francisco ‘Pacho’ Rodriquez into first place. It colluded with Delgado’s Orbea team, allowing Perico to make up a six-minute time deficit on the Scot Robert Millar who held the gold jersey.

With Delgado up the road and Millar and Rodriquez caught out, the Zor and Orbea riders rode themselves into the ground to put time into the Scottish climbing specialist.

It is even rumoured that Millar was delayed by a crossing which closed for a train that never came.

Delgado finished sufficiently ahead to take over the lead of GC and win the title. On the podium Delgado proclaimed, “My victory is all of Spain’s.”

Millar lamented: “They would rather see me lose and a Spaniard win.”

The race marked a dramatic change from the days when foreign riders like Maertens dominated the race while Spaniards engaged in internecine self-destruction.

* * * * *

For the first time since its inception almost 50 years before, the Vuelta saw the Spanish nation(s) united. Spain’s new federal model seemed to be working. Basques and Catalans, along with other regional riders, had come together on the roads of Spain to beat a Scot.

Like the new federal system, the cycling alliances allowed both the assertion of regional identities and the ability to be singularly ‘Spanish’ when it mattered.

Unlike any political efforts before it, this one remarkable day in pro cycling had genuinely crystallised a version of a unified Spain and foreshadowed the movida: the emergence of a vibrant Spain that would take place late in the 20th century.

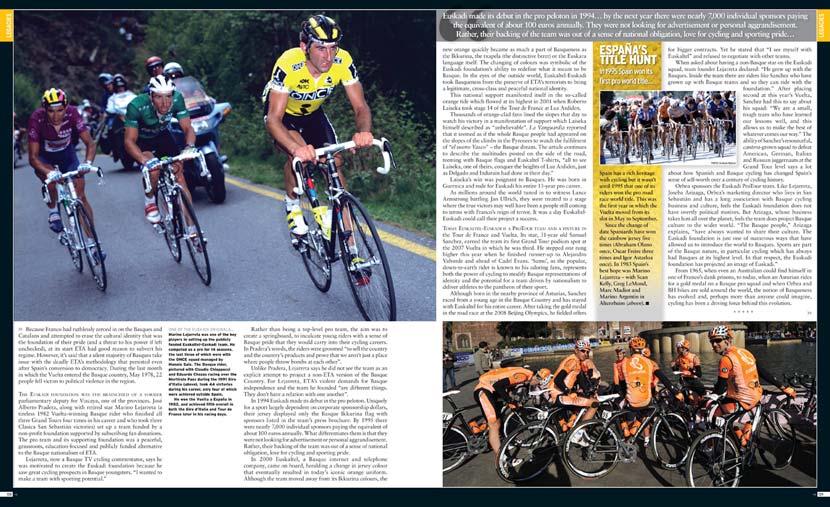

In the 1990s Basque rider Miguel Indurain inherited Perico’s mantle. As his biographer Javier García Sánchez notes, “Saying ‘Indurain’ was another way of saying ‘Spanish’… Miguel became the standard, the shield, the flag, the emblem.”

Although Indurain moved his focus from the Vuelta to domination of the Tour, he was idolised by the Spanish and Basque people. Myths spawned in cafes had him training in the bullring and drinking bull blood to enhance his virility.

Indurain was the embodiment of a new, stronger Spain for worldwide followers who saw him take five Tours de France, the Giro d’Italia title twice plus a gold medal in one of the last time trials of his career, the 1996 Olympics.

Thanks in part to Spain’s heritage of generating pro sports figures and teams as products and symbols of nationalistic pride, the last four Tour de France winners are Spanish.

In soccer, FC Barcelona was last year’s European Champion and this year’s Champions’ League victor. Rafael Nadal is world number two in tennis, Fernando Alonso was the Formula One champion twice, Samuel Sanchez took a gold medal in the cycling road race in Beijing and moved up a step on the 2009 Vuelta podium behind compatriot Alejandro Valverde, and Spain is the current international basketball federation world champion.

As for the future of Spain’s Grand Tour and Spain’s most passionate cycling heartland, the Pais Vasco, perhaps Orbea’s Arizaga puts it best: “Cycling fans live with passion. We don’t understand borders.

If the Tour goes through Italy, the Giro through Slovenia, and the Vuelta through Holland, why shouldn’t it pass through the Basque Country?”

[/et_pb_text][/et_pb_column][/et_pb_row][/et_pb_section]