Since 2004, RIDE Cycling Review has published the ‘Retro Review’ feature in every issue of the magazine. We have published features about the bikes of famous riders from the past and offered insight into the development of products over the years by looking at some of cycling’s finest machines. With another edition of Paris-Roubaix coming up on the weekend, we thought it as good a time as ever to revisit Warren Meade’s overview of Andrea Tafi’s Colnago C40 from 1999. This Flashback from RIDE #33 is yet another reminder that 15 years is a long time!

– Photos by Yuzuru Sunada

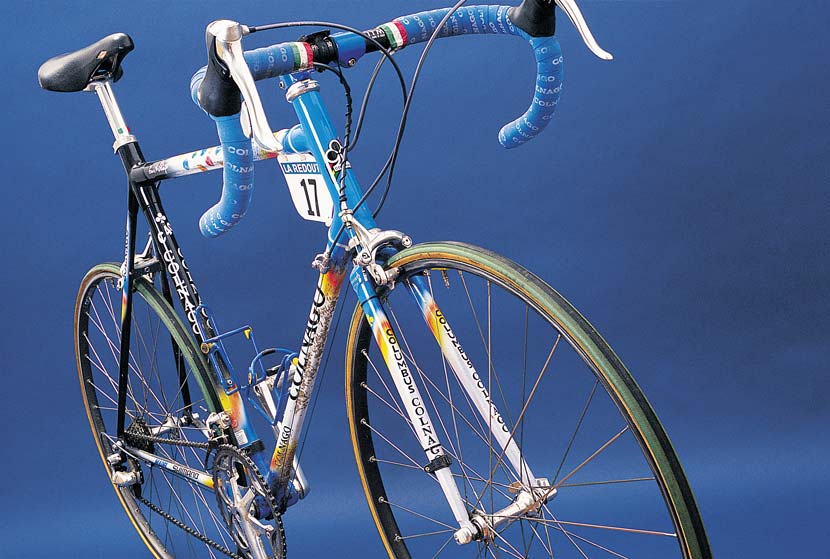

A carbon collectable… The instantly recognisable Colnago C40 in the famous Mapei team colours, proudly displaying the number 17 dossard of Andrea Tafi, winner of the 1999 Paris-Roubaix.

Photo: Yuzuru Sunada

Colnago: a Paris-Roubaix winner (a Retro Review from RIDE #33, published in July 2006)

During the years of the Mapei team three of its riders rode Colnago bikes to win Paris-Roubaix five times. We look at the machine Andrea Tafi used in 1999, the season of his success.

– By Warren Meade

This is the Colnago that Andrea Tafi rode to victory in the 1999 edition of Paris-Roubaix. The frame is the Colnago C40 of that year, equipped with Shimano Dura-Ace. Regular readers of this series may recall the story about Francesco Moser’s 1983 bike (RIDE #31) and the fact that he was the first Italian superstar to use Japanese components. He caused a scandal in Italy for using anything other than parts made in his homeland, and returned to the Campagnolo fold to equip his namesake Moser bikes the following year.

Things changed a lot between the uproar of 1983 and the 1999 season. The fact that this Colnago, arguably the most successful of the Italian race frame manufacturers, was equipped with Dura-Ace did not even cause a ripple, with Shimano having infiltrated the peloton to such an extent that it was now the majority shareholder.

There is a connection to Moser but it has nothing to do with equipment. When he won Paris-Roubaix for the third time, in 1980, he had done so wearing the jersey of the Italian champion. Tafi wore the equivalent top in 1999. He stated after the race that he wanted to repeat his childhood idol’s feat and it had given him great satisfaction to have done so.

Andrea Tafi was determined to win Paris-Roubaix. After podium places in the previous two editions, he was one of the short priced favourites on the morning of the race. But this event is more than just another race, it is a lottery. Roubaix is a rough ride for competitors and exceptionally hard on their equipment. It’s 273km of torture. This Spring Classic has sections of pavé that turn an otherwise normal point to point bike race into a spectacle of chaos, destruction and courage.

The aluminium ITM stem doubled up as a dashboard displaying all the sectors of pavé for the 97th edition (above).

Photo: Yuzuru Sunada

Technology had been developing for 120 years when Tafi mounted his Colnago on 11 April 1999. The attributes of successful riders hadn’t changed much during the 96 previous editions of the Hell of the North but the latest bikes bore absolutely no resemblance to the machines of the 1890s.

From the very first edition good equipment and a bit of luck played a role in the result. As the decades passed by, other courses were cleaned up and modernised but Paris-Roubaix continued to be a reminder of how bad roads used to be. This is probably a good thing for the development of equipment.

I’m sure the designers of exotic parts will have considered that whatever they create – no matter how light, aerodynamic and aesthetically pleasing – it must be able to stand up to the rigours of the world’s toughest race. If a vital part made by a major manufacturer fails en route to Roubaix, television viewers around the world witness it. If a part or groupset can survive Paris Roubaix, it provides a solid endorsement.

In 1896 the riders made do with a sturdy bike with two wheels, two pedals and not much else. The average speed for the first race was 30.16kph. A few years later the stopping power of the first rim brakes was a sign of progress. Just before World War One were other developments including a choice of two gear ratios that required the rider to dismount and change the wheel around to effect a change.

The 1930s saw the introduction of rudimentary three-speed derailleurs. In the 1940s came the advent of two chainrings and four cogs on the rear, giving a total of eight gears.

On a machine built to last the distance on the roughest surfaces a road bike is ever likely to encounter, the ITM Pro 260 bars were superlight at the top (weighing just 260g). They might have been an optimistic choice but obviously passed what many consider to be the ultimate test.

Photo: Yuzuru Sunada

In 1985, following 30 years of relatively minor upgrades in equipment, Shimano successfully introduced indexed gears. This came after a failed attempt with the Positron system in 1977. By now there were six cogs on the back. The indexing innovation eventually led to the possibility of incorporating the gear controls into the brake levers, which the component manufacturer succeeded in doing in 1990.

Dual control – or STI, Shimano Total Integration – levers revolutionised road racing. They allowed cyclists to shift under load and whilst riding out of the saddle or sprinting.

I remember the first time I saw someone use STI levers. On a hilly course I was in a two-man escape with the rider who was so equipped. Like most of the rest of the peloton, I had downtube levers. Going up a long and steep hill, both of us climbing out of the saddle for most of it, my opponent was constantly shifting gears and altering the pace. Every time he changed gears I would have to sit down, shift and then stand up again. This meant each time he shifted, I’d lose two bike lengths. I ordered a STI groupset a few days later.

The 1999 incarnation of Dura-Ace is displayed on Tafi’s iconic Colnago. The STI system had grown to 18 ratios by 1997 and the cranks were now hollow aluminium. The C40 frame is lugged carbon with the tubing cross-section following the Gilco form as used by Colnago in its Master series of frames from the late 1970s onwards. You may notice that the frame tubes have a ‘crimped’ look. This unique profile was said to increase stiffness; whether it did or not is arbitrary but it certainly added to the Colnago-ness of the C40 package.

The lightweight but robust hollow Shimano Dura-Ace cranks, with the standard 53-tooth nickel plated outer chainring, and an aftermarket unbranded 46-tooth inside ring. A big ratio for a powerful man…!

Photo: Yuzuru Sunada

Several aspects of this bike differ from the normal team issue. The inside chainring has been swapped from the usual 39-tooth nickel plated Dura-Ace item to an unbranded 46-tooth plain aluminium one. A simple plastic clip has been clamped around the seat tube just below the front derailleur. This is a chain catcher, placed there to prevent the chain from jumping off and getting jammed at the bottom bracket. Accidental unshippings of the chain are an occupational hazard at Paris-Roubaix.

The rims are beefed-up Ambrosio Durex items, heavier than those used in other races, and the tyres are Vittoria tubulars with a larger than normal section. (Tafi was luckier than most, he only punctured once during the 1999 race.) The tops of the bars have been padded prior to the tape being applied, and the Rolls seat is a special model with extra padding.

Shimano may have infiltrated the pro peloton by 1999 but one major result had eluded them. That record was soon to be amended; only 15 weeks after Paris-Roubaix, a revitalised Lance Armstrong broke through to win his first Tour de France. He rode a Trek equipped with Dura-Ace, and the start of his reign at the Tour heralded the end of the 50-year domination of the event by Campagnolo-equipped bikes.

In 1999, Andrea Tafi won Paris-Roubaix by over two minutes. The rider performed well, the bike survived in tact save for the one puncture. He rode his last Paris-Roubaix in 2005 at the age of 39 and retired shortly afterwards. He finished in a credible 42nd place, just four minutes and 52 seconds behind the winner, that man Tom Boonen.

2. Extra padding has been added to the top of Tafi’s bars beneath the Colnago-branded cork tape. Down near the bottom bracket you can see the low-tech yet very sensible plastic chain catcher on the seat tube. The Columbus steel fork and the authentic mud collected during the 97th edition of Paris-Roubaix can all be seen in this shot.

Photo: Yuzuru Sunada