In May 2002, Cadel Evans became the first Australian to wear the maglia rosa in the Giro d’Italia. He wore it for one day. It was his first Grand Tour. In May 2010, he wore the maglia rosa again – swapping his world championship jersey for a pink one… for one day. He would win the points classification that year. And he would return to the Giro again in 2013 and finish third overall, the first Aussie on the GC podium of the Italian race.

Twelve years ago, RIDE published the following feature on Evans and his first Giro.

Today, as we publish this flashback (18 May 2014) he will wear the maglia rosa for a third day. This time, it seems like his leadership tenure could last longer than one day.

The story below is from RIDE #17, published in June 2002…

(For another perspective of that most interesting day for Australian cycling, see our interview with Dario Cioni one of Evans’ key domestiques during the 2002 Giro d’Italia.)

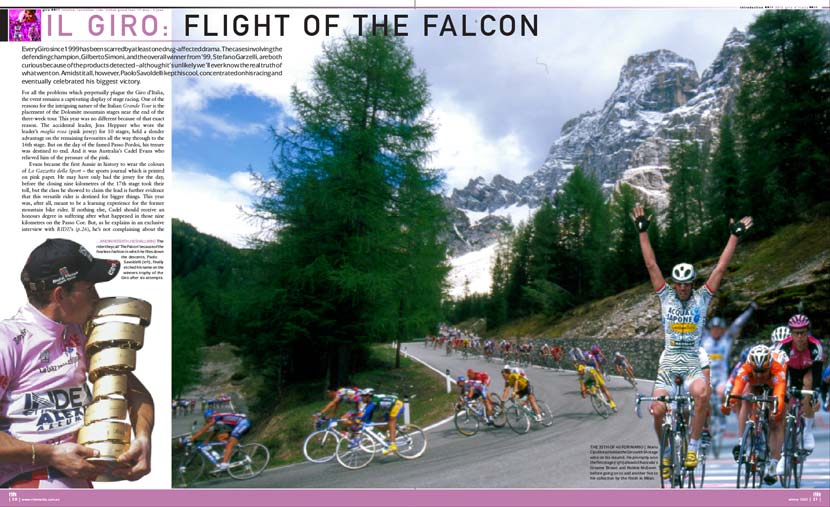

Every Giro since 1999 has been scarred by at least one drug-affected drama. The cases involving the defending champion, Gilberto Simoni, and the overall winner from 1999, Stefano Garzelli, are both curious because of the products detected – although it’s unlikely we’ll ever know the real truth of what went on. Amidst it all, however, Paolo Savoldelli kept his cool, concentrated on his racing and eventually celebrated his biggest victory.

For all the problems which perpetually plague the Giro d’Italia, the event remains a captivating display of stage racing. One of the reasons for the intriguing nature of the Italian Grande Tour is the placement of the Dolomite mountain stages near the end of the three-week tour. This year was no different because of that exact reason. The accidental leader, Jens Heppner who wore the leader’s maglia rosa (pink jersey) for 10 stages, held a slender advantage on the remaining favourites all the way through to the 16th stage. But on the day of the famed Passo Pordoi, his tenure was destined to end. And it was Australia’s Cadel Evans who relieved him of the pressure of the pink.

Evans became the first Aussie in history to wear the colours of La Gazzetta della Sport – the sports journal which is printed on pink paper. He may have only had the jersey for the day, before the closing nine kilometres of the 17th stage took their toll, but the class he showed to claim the lead is further evidence that this versatile rider is destined for bigger things. This year was, after all, meant to be a learning experience for the former mountain bike rider. If nothing else, Cadel should receive an honours degree in suffering after what happened in those nine kilometres on the Passo Coe. But, as he explains in an exclusive interview with RIDE, he’s not complaining about the experience.

Interview – Cadel Evans: pink for a day

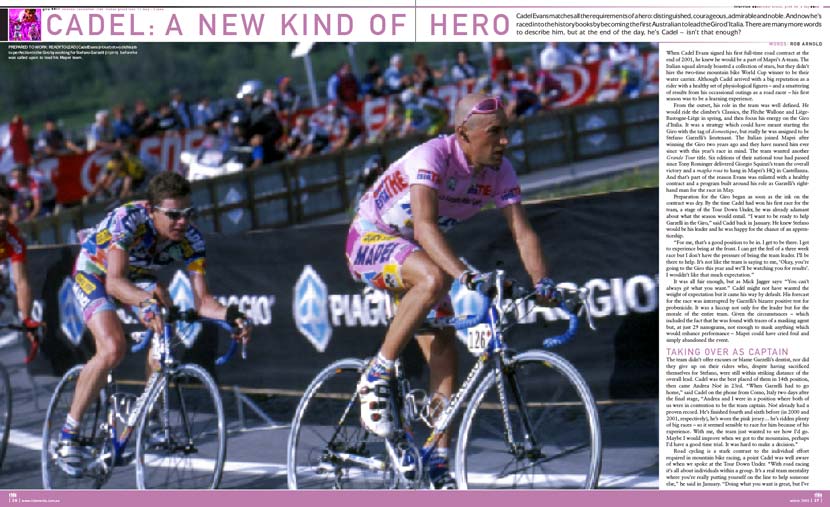

Cadel Evans matches all the requirements of a hero: distinguished, courageous, admirable and noble. And now he’s raced into the history books by becoming the first Australian to lead the Giro d’Italia. There are many more words to describe him, but at the end of the day, he’s Cadel – isn’t that enough?

When Cadel Evans signed his first full-time road contract at the end of 2001, he knew he would be a part of Mapei’s A-team. The Italian squad already boasted a collection of stars, but they didn’t hire the two-time mountain bike World Cup winner to be their water carrier. Although Cadel arrived with a big reputation as a rider with a healthy set of physiological figures – and a smattering of results from his occassional outings as a road racer – his first season was to be a learning experience.

From the outset, his role in the team was well defined. He would ride the climber’s Classics, the Flèche Wallonne and Liège-Bastogne-Liège in spring, and then focus his energy on the Giro d’Italia. It was a strategy which could have meant starting the Giro with the tag of domestique, but really he was assigned to be Stefano Garzelli’s lieutenant. The Italian joined Mapei after winning the Giro two years ago [2000] and they have nursed him ever since with this year’s race in mind. The team wanted another Grande Tour title. Six editions of their national tour had passed since Tony Rominger delivered Giorgio Squinzi’s team the overall victory and a maglia rosa to hang in Mapei’s HQ in Castellanza. And that’s part of the reason Evans was enlisted with a healthy contract and a program built around his role as Garzelli’s right-hand man for the race in May.

Preparation for the Giro began as soon as the ink on the contract was dry. By the time Cadel had won his first race for the team, a stage of the Tour Down Under, he was already adamant about what the season would entail. “I want to be ready to help Garzelli in the Giro,” said Cadel back in January. He knew Stefano would be his leader and he was happy for the chance of an apprenticeship.

“For me, that’s a good position to be in. I get to be there. I get to experience being at the front. I can get the feel of a three week race but I don’t have the pressure of being the team leader. I’ll be there to help. It’s not like the team is saying to me, ‘Okay, you’re going to the Giro this year and we’ll be watching you for results’. I wouldn’t like that much expectation.”

… Cadel might not have wanted the weight of expectation but it came his way by default. His forecast for the race was interrupted by Garzelli’s bizarre positive test for probenicide. It was a hiccup not only for the leader but for the morale of the entire team. Given the circumstances – which included the fact that he was found with traces of a masking agent but, at just 29 nanograms, not enough to mask anything which would enhance performance – Mapei could have cried foul and simply abandoned the event.

Taking Over As Captain

The team didn’t offer excuses or blame Garzelli’s dentist, nor did they give up on their riders who, despite having sacrificed themselves for Stefano, were still within striking distance of the overall lead. Cadel was the best placed of them in 14th position, then came Andrea Noé in 23rd. “When Garzelli had to go home,” said Cadel on the phone from Como, Italy two days after the final stage, “Andrea and I were in a position where both of us were in contention to be the team captain. Noé already had a proven record. He’s finished fourth and sixth before (in 2000 and 2001, respectively), he’s worn the pink jersey… he’s ridden plenty of big races – so it seemed sensible to race for him because of his experience. With me, the team just wanted to see how I’d go. Maybe I would improve when we got to the mountains, perhaps I’d have a good time trial. It was hard to make a decision.”

Road cycling is a stark contrast to the individual effort required in mountain bike racing, a point Cadel was well aware of when we spoke at the Tour Down Under. “With road racing it’s all about individuals within a group. It’s a real team mentality where you’re really putting yourself on the line to help someone else,” he said in January. “Doing what you want is great, but I’ve been in a situation like that for seven years.”

After the 10th stage, however, Mapei decided they would ride for both Cadel and Noé up until the time trial and determine the leader after that. “The time trial went well but stage 13 was the turning point,” explained Cadel of the moment he was christened team captain. “That day in the mountains confirmed I was riding a bit better than Andrea. After that it was a case of, ‘Okay, Cadel’s going a little better, he can take over the team leadership’. But, at Mapei, it’s not as though we were fighting for the role of leader. We both rode through to the mountains knowing that the best rider would get the support of the team.”

Racing into History

In the 13th stage, Cadel finished second behind the diminutive Mexican climber, Julio Perez, and jumped to fifth overall. In the time trial the next day, Cadel was third. Not only did he prove that his body could recover from the pain caused by the climbs, he also moved up to second on GC. That’s when things really got interesting – but also frustrating because it was clear there were two distinct objectives for the strong riders still in the race: the quest for stage success and the battle for the overall title. Cadel’s interests lay with the latter. “The 13th stage was a little disappointing,” said Cadel of the day he came closest to a stage win.

“I was in a position where I had to ride for GC, but Perez was only riding for the stage. As soon as I got away with him, he didn’t want to work. When that became apparent, I was frustrated with his lack of professionalism. He’s a great rider and the way he climbs is amazing but his tactics were annoying. He was only thinking about the stage win and I had to think about gaining time. I would have been happy to have worked harder with him because, at that point in time, the main thing to get out of that stage was to take as much time as possible out of Casagrande and Frigo.”

Indeed, Francesco Casagrande and Dario Frigo seemed the two riders who were most likely to upset Cadel’s quest for the pink jersey. That was until Casagrande put himself out of contention when he was DQ-ed in stage 15 for causing a crash which netted Fredy Garcia 30 stitches to his face and retirement from the race.

Frigo, on the other hand, not only stayed in the race, he also led home Cadel’s select group to finish third behind Perez and Savoldelli. That stage crossed the fearsome 2,239m Passo Pordoi. From there it was a dangerous seven kilometre descent, one more climb (the 1,875m Passo di Campolongo) and a downhill rush to the finish.

“I was actually quite nervous that morning,” said Cadel about the start of stage 16. “That’s because I knew Heppner couldn’t last another day. I was anxious but only because things were looking good for me.” At the finish, things looked better than good. Mapei’s new team leader was seventh in the stage, but the best rider overall – therefore becoming the first Australian to ever lead the Giro.

“At the particular moment I got the jersey, it was a bit surreal,” explained Cadel. “I’ll probably look back on that in a few weeks or a few years and think, ‘Oh wow, that was amazing!’ But there was so much going on that it was all a little confusing. It was like, ‘Hang on, where am I going? Oh, I’m going to the podium? You want me to stand up there… oh, look what I’ve got, I don’t have to wear my Mapei jersey, I’ve got another one.”

Goodbye Rosa!

At the start of the 220km 17th stage, Cadel seemed in control. He sat comfortably behind his team-mates for the early phase of his day in pink. On paper, the main riders to watch were Frigo and the American hope, Tyler Hamilton. But there were still five riders within 48 seconds of his lead. What he had to do was simple in theory: ride tempo, cover the dangerous attacks, finish in the lead group… and hope that he had a leading margin big enough to ensure that he enjoyed the finishing parade into Milan.

It’s easy to say while watching the coverage from the comfort of your home in Australia, and as we followed RAI International’s pictures through the valley which led to the Passo Coe (the final real mountain of the race) it seemed as though Cadel was doing just that. He was up front and in control. He followed the wheel of Dario Cioni, another former mountain bike star who was now setting the pace for his Mapei team-mate. Then Noé took charge and his pace on the early parts of the climb dropped Frigo.

“I think I was climbing a little bit better than Frigo was,” said Cadel of the rider who pipped him for the win on the Col d’Eze stage of Paris-Nice in March. “He got some time on me when I was working for Garzelli, but otherwise I was just a little way ahead of him each step of the way. I lost a bit of time when I won the jersey, but then I was riding for time not a stage placing. In the time trials and the hilltop finishes I was riding just a little better than him.”

Not even a last-minute gulp of a Red Bull energy drink could save the bleached-blonde Italian. He blew with 12km to race. In our lounge room, Frigo was scratched off the list. Gone! But there were other victims of that final climb. Cadel explains: “I was on the wheel of Andrea. He was setting a really good pace. Frigo had just been shelled and everything was going along rather well… but, um, after 211km of racing in the mountains it was starting to hurt. Noé was upping the pace – pushing harder and harder to stop any attacks – and I left a bit of a gap. I wouldn’t say I was feeling really tired, I was just talking on the radio and lost a little bit of concentration. Hamilton saw the gap and he went on the attack… then, all of sudden, bang! My lights went out.

“When Hamilton attacked, I had to make another surge and that was the very last drop of fuel. I was just completely empty. I wasn’t the only one. I spoke to Frigo and Hamilton later and they agreed that it wasn’t so much the 17th stage which was bad; it was that it came after the 16th – which was also a long, hard day.

“Just to start such a long stage in the mountains is daunting, but to have to defend the lead makes it even harder. We spent most of the stage at the front trying to control the race and that took a little bit of extra energy.”

There was plenty of time to discuss what went wrong as we watched Cadel crawl up the mountain. The publisher of cyclingnews.com, Gerard Knapp had come over to watch what we hoped would be a celebration. Once Cadel blew, however, we whispered possible problems to each other and waited for Cadel to get to the line. “Perhaps he didn’t eat,” I suggested. “It’s a hard eight-hour day,” said Gerard. But it was my girlfriend, Nicola, who offered the logical explanation: “He’s only young. He’s in his first three week race. He’s only been with Mapei since January. Put it down to experience, he’s still learning.” Exactly!

“You would not believe how much food I ate that day,” said Cadel when I later searched for confirmation of the reason for his explosion. “Eating wasn’t the problem – it was a combination of many things. It was my first big tour, we’d been racing hard for 17 days, I had the pressure of the pink jersey… and 17 days isn’t very long compared to Tonkov’s seven years of preparation or Savoldelli’s lessons from five previous Giros.”

Indeed it was the eventual champion who pointed out that talent can make you a great bike rider, but experience is what will win a race like the Giro. And Cadel was happy that the jersey he held briefly went to someone of Paolo’s stature. “I gained a lot of respect for Savoldelli because of his comments and the high regard that he has for his competitors,” said Cadel. “He also showed that he’s learnt from his previous efforts in the Giro. At the end of a three week tour when it’s a high pressure situation, your mental strength comes into play – and the situation played perfectly into the hands of Savoldelli.”

[Read Dario Cioni’s take on the 17th stage…]

Evans, his first day in the pink jersey at the Giro d’Italia. Stage 17, 2002.

Photo: Graham Watson

The future of Cadel

He may have blown before the summit and lost the lead, but Cadel learned a lot from those painful nine kilometres of climbing. He’s shown his potential and bigger things await him. The Tour de France, however, is still likely to be a few years away [remember, this is from 2002, he’d make his Tour debut in 2005]. He’s happy to listen to Mapei’s advice, and it’s likely they’ll suggest another crack at the Italian race. “I think they’d like to keep me focused on the Giro,” said Cadel about his plans for next year. “Garzelli has probably had enough of the Giro and that’s pretty reasonable. Of course I want to ride the Tour de France, but another year of riding the Giro would be another year I can gain experience and maintain the progressive approach Mapei are interested in. I’m happy to take it that way.

“Maybe I am missing a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity by not riding the Tour this year, but I think I’ve got time and I’ll ride it when I’m ready. The Giro is a race I like. I’m in an Italian team and it’s a race that’s important to us. And the Italians don’t mind cheering on a little Aussie guy.”

The cheers of the fans is one way to motivate a “little Aussie guy” to return, but the pressure of being a leader of an Italian team in the Italian race would be enough to stress anyone. Cadel isn’t a stranger to dealing with high expectations. He experienced the weight of being the perpetual favourite during his time as a mountain biker, so did that serve him well when he was faced with the intensity of leading the Giro this year? “Absolutely! For me to go to the Olympics in Australia as one of the favourites was a real pressure situation. To lead the Giro was easier to handle,” said Cadel without hesitation. “Maybe there was more pressure, but there are also many more people to help carry the burden. The riders, the staff, the directors – there was always someone around to help me out and make sure I had time for myself. The Mapei team is amazing. It’s a really positive experience for me to be with a team like this. I can help share the good and the bad with other riders. I never had that sort of feeling with mountain biking.

When asked if there was anything he wanted to add to this interview Cadel was quick to reply. “I think a lot of people get the impression I made a mistake when I ran out of gas. The problem was that I’ve only been road racing for six months and the human body takes a bit of time to adapt to these different workloads. That is the only thing that went wrong.”

And so it seems, Nicola’s summation of Cadel’s dire situation was accurate. She has learned a lot about cycling in the past few years. She’s met most of Australia’s pros and enjoys hearing of their trials and tribulations. Her brief encounter with Cadel a few years ago left a positive impression. When asked to summarise her thoughts on him, she responded quickly and concisely. “Quiet. Strong. Determined. Driven. Dedicated. He’s not a party boy. He’s not frivolous. He knows what he wants and seems prepared to work hard for it. He’s Cadel.” All true…

– By Rob Arnold

(first published, RIDE Cycling Review #17 2002)