In RIDE #66 we introduced a series about what it was like to race as part of the Soviet system. Written by Nikolai Razouvaev, it offers a first-hand account of something that is often referenced in commentary but rarely properly understood. The feature is part of an ongoing story that will continue to be told in future issues of our magazine.

As we finish up another edition, here is an excerpt from the opening article by Razouvaev.

(Read the full story in RIDE #66, on sale now – in newsagents, bike shops and as an e-magazine.)

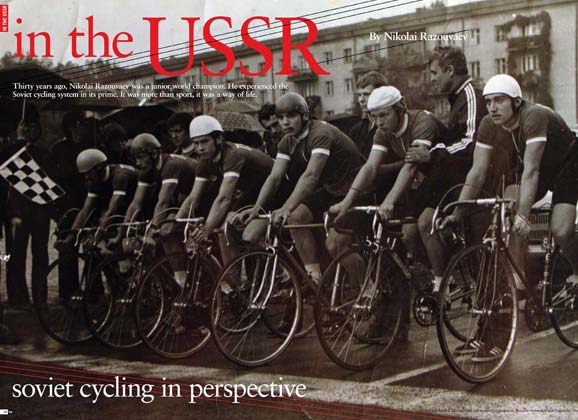

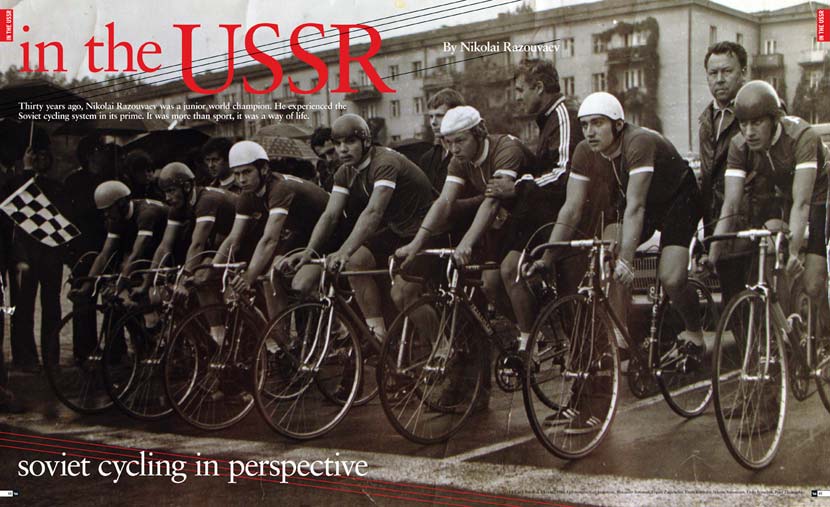

TTT in Uzhhorod, Ukraine, 1984. Left to right: Yuri Arakelyan, Alexander Botzman, Evgeny Zagrebelny, Vitaly Kozinsky, Nikolai Razouvaev, Vitaly Franchuk, Peter Zhukovsky.

In the USSR – Soviet cycling in perspective

– By Nikolai Razouvaev

Thirty years ago, Nikolai Razouvaev was a junior world champion. He experienced the Soviet cycling system in its prime. It was more than sport, it was a way of life.

In this great future, Bob Marley once sang, you can’t forget your past. A good deal of my past is buried in a country you can’t find on a map anymore. Once a mighty, all-conquering powerhouse, it crashed to the ground as violently as it rose to the global stage in 1917, waving a red flag in one hand and shaking a fist at the rest of the world with the other. We stood alone, our teachers taught us. In the sea of capitalism, an inhumane system of exploitation and greed, we were the first nation on earth to stand up from our proletarian knees to start a new era in human history, a new social order of equality, peace and prosperity.

We turned an agrarian, feudal empire into a leading industrial nation in two decades. We laid down 30 million of our fellow men to rid the world of Nazism. We rose from the rubble and ashes of the WWII and launched the first spacecraft in the history of humankind. To safeguard our way of life, we built a nuclear arsenal deadly enough to destroy the planet more than once.

Firmly on our feet and with the world rotting away in its immoral pursuit of riches, by the 1950s we were ready to show socialism’s superiority in the sporting arena.

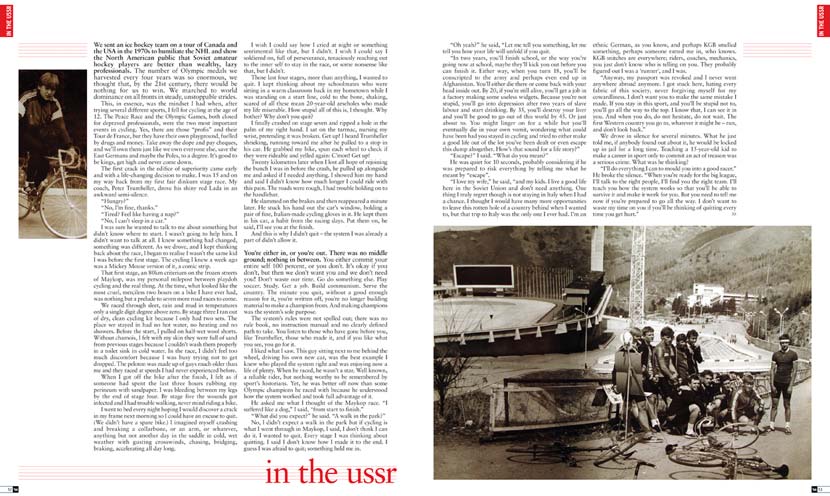

We sent an ice hockey team on a tour of Canada and the USA in the 1970s to humiliate the NHL and show the North American public that Soviet amateur hockey players are better than wealthy, lazy professionals. The number of Olympic medals we harvested every four years was so enormous, we thought that, by the 21st century, there would be nothing for us to win. We marched to world dominance on all fronts in steady, unstoppable strides.

This, in essence, was the mindset I had when, after trying several different sports, I fell for cycling at the age of 12. The Peace Race and the Olympic Games, both closed for depraved professionals, were the two most important events in cycling. Yes, there are those “profis” and their Tour de France, but they have their own playground, fuelled by drugs and money. Take away the dope and pay cheques, and we’ll own them just like we own everyone else, save the East Germans and maybe the Poles, to a degree. It’s good to be kings, get high and never come down.

The first crack in the edifice of superiority came early and with a life-changing decision to make. I was 15 and on my way back from my first fair dinkum stage race. My coach, Peter Trumheller, drove his shiny red Lada in an awkward semi-silence.

“Hungry?”

“No, I’m fine, thanks.”

“Tired? Feel like having a nap?”

“No, I can’t sleep in a car.”

I was sure he wanted to talk to me about something but didn’t know where to start. I wasn’t going to help him. I didn’t want to talk at all. I knew something had changed, something was different. As we drove, and I kept thinking back about the race, I began to realise I wasn’t the same kid I was before the first stage. The cycling I knew a week ago was a Mickey Mouse version of it, a comic strip.

That first stage, an 80km criterium on the frozen streets of Maykop, was my personal milepost between playdoh cycling and the real thing. At the time, what looked like the most cruel, merciless two hours on a bike I have ever had, was nothing but a prelude to seven more road races to come.

We raced through sleet, rain and mud in temperatures only a single digit degree above zero. By stage three I ran out of dry, clean cycling kit because I only had two sets. The place we stayed in had no hot water, no heating and no showers. Before the start, I pulled on half-wet wool shorts. Without chamois, I felt with my skin they were full of sand from previous stages because I couldn’t wash them properly in a toilet sink in cold water. In the race, I didn’t feel too much discomfort because I was busy trying not to get dropped. The peloton was made up of guys much older than me and they raced at speeds I had never experienced before.

When I got off the bike after the finish, I felt as if someone had spent the last three hours rubbing my perineum with sandpaper. I was bleeding between my legs by the end of stage four. By stage five the wounds got infected and I had trouble walking, never mind riding a bike.

I went to bed every night hoping I would discover a crack in my frame next morning so I could have an excuse to quit. (We didn’t have a spare bike.) I imagined myself crashing and breaking a collarbone, or an arm, or whatever, anything but not another day in the saddle in cold, wet weather with gusting crosswinds, chasing, bridging, braking, accelerating all day long.

I wish I could say how I cried at night or something sentimental like that, but I didn’t. I wish I could say I soldiered on, full of perseverance, tenaciously reaching out to the inner self to stay in the race, or some nonsense like that, but I didn’t.

Those last four stages, more than anything, I wanted to quit. I kept thinking about my schoolmates who were sitting in a warm classroom back in my hometown while I was standing on a start line, cold to the bone, shaking, scared of all these mean 20-year-old arseholes who made my life miserable. How stupid all of this is, I thought. Why bother? Why don’t you quit?

I finally crashed on stage seven and ripped a hole in the palm of my right hand. I sat on the tarmac, nursing my wrist, pretending it was broken. Get up! I heard Trumheller shrieking, running toward me after he pulled to a stop in his car. He grabbed my bike, spun each wheel to check if they were rideable and yelled again: C’mon! Get up!

Twenty kilometres later when I lost all hope of rejoining the bunch I was in before the crash, he pulled up alongside me and asked if I needed anything. I showed him my hand and said I didn’t know how much longer I could ride with this pain. The roads were rough, I had trouble holding on to the handlebar.

He slammed on the brakes and then reappeared a minute later. He stuck his hand out the car’s window, holding a pair of fine, Italian-made cycling gloves in it. He kept them in his car, a habit from the racing days. Put them on, he said, I’ll see you at the finish.

And this is why I didn’t quit – the system I was already a part of didn’t allow it.

You’re either in, or you’re out. There was no middle ground; nothing in between. You either commit your entire self 100 percent, or you don’t. It’s okay if you don’t, but then we don’t want you and we don’t need you! Don’t waste our time. Go do something else. Play soccer. Study. Get a job. Build communism. Serve the country. The minute you quit, without a good enough reason for it, you’re written off, you’re no longer building material to make a champion from. And making champions was the system’s sole purpose.

The system’s rules were not spelled out; there was no rule book, no instruction manual and no clearly defined path to take. You listen to those who have gone before you, like Trumheller, those who made it, and if you like what you see, you go for it.

I liked what I saw. This guy sitting next to me behind the wheel, driving his own new car, was the best example I knew who played the system right and was enjoying now a life of plenty. When he raced, he wasn’t a star. Well known, a reliable rider, but nothing worthy to be remembered by sport’s historians. Yet, he was better off now than some Olympic champions he raced with because he understood how the system worked and took full advantage of it.

He asked me what I thought of the Maykop race. “I suffered like a dog,” I said, “from start to finish.”

“What did you expect?” he said. “A walk in the park?”

No, I didn’t expect a walk in the park but if cycling is what I went through in Maykop, I said, I don’t think I can do it. I wanted to quit. Every stage I was thinking about quitting. I said I don’t know how I made it to the end. I guess I was afraid to quit; something held me in.

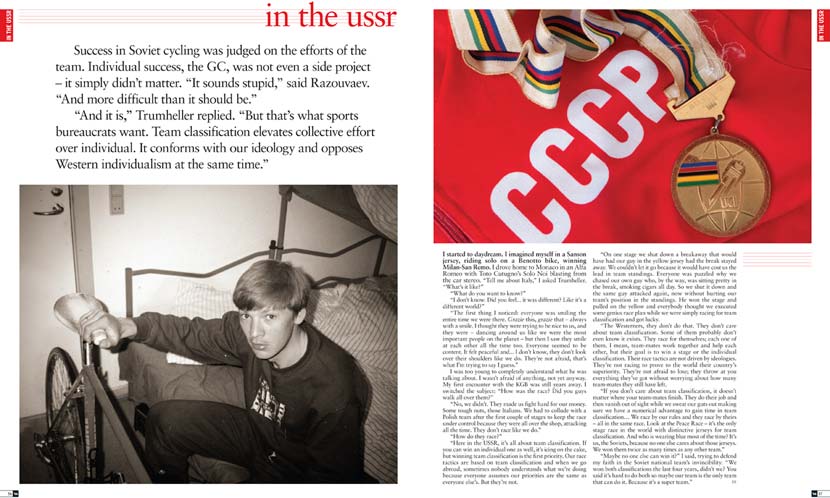

“Oh yeah?” he said, “Let me tell you something, let me tell you how your life will unfold if you quit.

“In two years, you’ll finish school, or the way you’re going now at school, maybe they’ll kick you out before you can finish it. Either way, when you turn 18, you’ll be conscripted to the army and perhaps even end up in Afghanistan. You’ll either die there or come back with your head inside out. By 20, if you’re still alive, you’ll get a job in a factory making some useless widgets. Because you’re not stupid, you’ll go into depression after two years of slave labour and start drinking. By 35, you’ll destroy your liver and you’ll be good to go out of this world by 45. Or just about to. You might linger on for a while but you’ll eventually die in your own vomit, wondering what could have been had you stayed in cycling and tried to either make a good life out of the lot you’ve been dealt or even escape this dump altogether. How’s that sound for a life story?”

“Escape?” I said. “What do you mean?”

He was quiet for 10 seconds, probably considering if he was prepared to risk everything by telling me what he meant by “escape”.

– By Nikolai Razouvaev

(Find the full feature in RIDE #66.)