Cycling isn’t complicated. It’s about you and what you choose to do with your bike. Where you ride, how you ride, and with whom you ride all influence your enjoyment from the act of cycling. When it comes to The Bunch, there are a few fundamental rules that should be adhered to – some are spoken, others assumed. In the first feature of RIDE #63, James Stout considers the cycling bunch and what it has to offer.

This is a most poignant story at a time when bunch riding is more prevalent on our roads than it has been for a long time. If you’ve ridden all your life or are new to the sport, this is a reminder of how important etiquette is in the cycling bunch. Please share this story with anyone you know who rides.

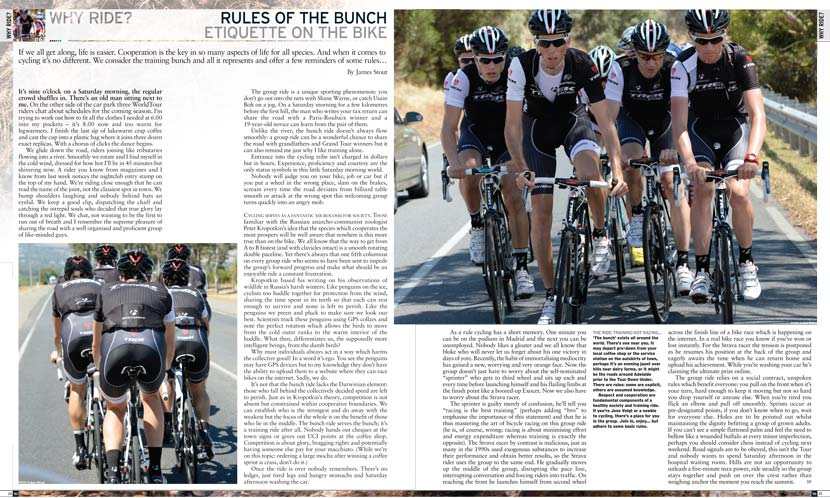

The Trek Factory Racing team formed a training bunch of its own in the days leading up to the Tour Down Under this January.

Photo: Graham Watson.

“We all benefit from all of us getting better…”

– By James Stout

If we all get along, life is easier. Cooperation is the key in so many aspects of life for all species. And when it comes to cycling it’s no different. We consider the training bunch and all it represents and offer a few reminders of some rules…

It’s nine o’clock on a Saturday morning, the regular crowd shuffles in. There’s an old man sitting next to me. On the other side of the car park three WorldTour riders chat about schedules for the coming season. I’m trying to work out how to fit all the clothes I needed at 6.00 into my pockets – it’s 8.00 now and too warm for legwarmers. I finish the last sip of lukewarm crap coffee and cast the cup into a plastic bag where it joins three dozen exact replicas. With a chorus of clicks the dance begins.

We glide down the road, riders joining like tributaries flowing into a river. Smoothly we rotate and I find myself in the cold wind, dressed for how hot I’ll be in 45 minutes but shivering now. A rider you know from magazines and I know from last week notices the nightclub entry stamp on the top of my hand. We’re riding close enough that he can read the name of the joint, not the classiest spot in town. We bump shoulders laughing and nobody behind bats an eyelid. We keep a good clip, dispatching the chaff and catching the intrepid souls who decided that true glory lay through a red light. We chat, not wanting to be the first to run out of breath and I remember the supreme pleasure of sharing the road with a well organised and proficient group of like-minded guys.

The group ride is a unique sporting phenomenon: you don’t go out into the nets with Shane Warne, or catch Usain Bolt on a jog. On a Saturday morning for a few kilometres before the first hill, the man who writes your tax return can share the road with a Paris-Roubaix winner and a 19-year-old novice can learn from the pair of them.

Unlike the river, the bunch ride doesn’t always flow smoothly: a group ride can be a wonderful chance to share the road with grandfathers and Grand Tour winners but it can also remind me just why I like training alone.

Entrance into the cycling tribe isn’t charged in dollars but in hours. Experience, proficiency and courtesy are the only status symbols in this little Saturday morning world.

Nobody will judge you on your bike, job or car but if you put a wheel in the wrong place, slam on the brakes, scream every time the road deviates from billiard table smooth or attack at the wrong spot this welcoming group turns quickly into an angry mob.

Cycling serves as a fantastic microcosm for society. Those familiar with the Russian anarcho-communist zoologist Peter Kropotkin’s idea that the species which cooperates the most prospers will be well aware that nowhere is this more true than on the bike. We all know that the way to get from A to B fastest (and with clavicles intact) is a smooth rotating double paceline. Yet there’s always that one fifth columnist on every group ride who seems to have been sent to impede the group’s forward progress and make what should be an enjoyable ride a constant frustration.

Kropotkin based his writing on his observations of wildlife in Russia’s harsh winters. Like penguins on the ice, cyclists too huddle together for protection from the wind, sharing the time spent in its teeth so that each can rest enough to survive and none is left to perish. Like the penguins we preen and pluck to make sure we look our best. Scientists track these penguins using GPS collars and note the perfect rotation which allows the birds to move from the cold outer ranks to the warm interior of the huddle. What then, differentiates us, the supposedly more intelligent beings, from the dumb birds?

Why must individuals always act in a way which harms the collective good? In a word it’s ego. You see the penguins may have GPS devices but to my knowledge they don’t have the ability to upload them to a website where they can race bikes on the internet. Sadly, we do.

It’s not that the bunch ride lacks the Darwinian element: those who fall behind the collectively decided speed are left to perish. Just as in Kropotkin’s theory, competition is not absent but constrained within cooperative boundaries. We can establish who is the strongest and do away with the weakest but the focus of the whole is on the benefit of those who lie in the middle. The bunch ride serves the bunch; it’s a training ride after all. Nobody hands out cheques at the town signs or gives out UCI points at the coffee shop. Competition is about glory, bragging rights and potentially having someone else pay for your macchiato. (While we’re on this topic: ordering a large mocha after winning a coffee sprint is crass, don’t do it.)

Once the ride is over nobody remembers. There’s no ledger, just tired legs and hungry stomachs and Saturday afternoon washing the car.

As a rule cycling has a short memory. One minute you can be on the podium in Madrid and the next you can be unemployed. Nobody likes a gloater and we all know that bloke who will never let us forget about his one victory in days of yore. Recently, the habit of immortalising mediocrity has gained a new, worrying and very orange face. Now the group doesn’t just have to worry about the self-nominated “sprinter” who gets to third wheel and sits up each and every time before launching himself and his flailing limbs at the finish point like a boozed-up Exocet. Now we also have to worry about the Strava racer.

The sprinter is guilty merely of confusion, he’ll tell you “racing is the best training” (perhaps adding “bro” to emphasise the importance of this statement) and that he is thus mastering the art of bicycle racing on this group ride (he is, of course, wrong: racing is about minimising effort and energy expenditure whereas training is exactly the opposite). The Strava racer by contrast is malicious, just as many in the 1990s used exogenous substances to increase their performance and obtain better results, so the Strava rider uses the group to the same end. He gradually moves up the middle of the group, disrupting the pace line, interrupting conversation and forcing riders into traffic. On reaching the front he launches himself from second wheel across the finish line of a bike race which is happening on the internet. In a real bike race you know if you’ve won or lost instantly. For the Strava racer the tension is postponed as he resumes his position at the back of the group and eagerly awaits the time when he can return home and upload his achievement. While you’re washing your car he’s claiming the ultimate prize online.

The group ride relies on a social contract, unspoken rules which benefit everyone: you pull on the front when it’s your turn, hard enough to keep it moving but not so hard you drop yourself or anyone else. When you’re tired you flick an elbow and pull off smoothly. Sprints occur at pre-designated points, if you don’t know when to go, wait for everyone else. Holes are to be pointed out whilst maintaining the dignity befitting a group of grown adults. If you can’t see a simple flattened palm and feel the need to bellow like a wounded buffalo at every minor imperfection, perhaps you should consider chess instead of cycling next weekend. Road signals are to be obeyed, this isn’t the Tour and nobody wants to spend Saturday afternoon in the hospital waiting room. Hills are not an opportunity to unleash a five-minute max power, ride steadily so the group stays together and push on over the crest rather than weighing anchor the moment you reach the summit.

We all want to show how strong we are, especially the week before a local race. The group ride has socially acceptable ways of doing that: take longer turns, push the old bloke, win the sprint, ride to the start, ride home.

Just because you were recently crowned C-grade world champion and bought a set of carbon hoops to celebrate doesn’t give you the right to disrupt the age-old rhythm of the bunch. So don’t run that red (don’t even accelerate for an orange light if you’re on the front), don’t chop wheels or half-wheel on the front, don’t pull out halfway up the bunch when you’re too tired, don’t alter the pace because you’re not in “the zone” or slam on the brakes when you get scared and please, never use a social ride in an attempt to increase your profile on social media.

Just as those penguins peck and flap to establish seniority, so the bunch ride has its own pecking order. This social hierarchy might not award little crowns you can post on Facebook but it does serve an important purpose.

Where racing concentrates ability and experience (and lack thereof) in the different grades, the wide range of abilities on a group ride allows the novice to benefit from the experience of the elite.

A well-structured bunch allows the older riders, with thousands of kilometres (and perhaps a bit less speed) in the legs to pass on that experience to the fit beginners (or, God forbid, triathletes) who think they can make up for a lack of experience with power meters and the internet. Watch the experienced riders on your next group ride and observe how they move up safely and slot in at the front (not halfway up the group), how they pull smoothly and flick their elbows to indicate the end of a turn, how they ride bar to bar calmly pointing out obstacles. It’s serene and effortless, like a locomotive running at full steam. Then watch the novices overlap wheels, dive-bomb corners and screech to a halt halfway around or engage the reverse gear on their new 11-speed groupset when standing on a climb, listen to them holler “inside” as if announcing their perilous intentions makes them somehow acceptable. It’s like that same engine only misfiring and tearing itself apart. A good group ride will teach a willing apprentice how to fit in. Sometimes the teaching will be explicit and often it will come simply from watching, and copying, those who know better.

Stronger riders could’ve ridden as hard or harder alone, they dictate the pace of the bunch and ride in the wind. They chose to ride with people, to enjoy the social aspect of cycling. It’s easy for us to forget that the bunch ride is, primarily, a social event. A gentle hand on the back, a quiet “hey mate” at the cafe or the offer of a wheel to follow are all it takes to begin the process of osmosis which brings a hairy-legged newbie into the gang.

Cycling is about belonging, about being part of the tribe. We have our rites of passage: your first time shaving your legs, and breaking your clavicle, your first hunger flat, and that first saddle-sore. The bunch ride is where we’re socialised to fit in with this society, where we learn that cyclists shave their legs (although nobody is entirely clear on why), that you have to take your knicks off as soon as you’re finished riding, why and how echelons form and that somehow the holy grail of cycling is to ride in a country where it’s flat, wet, cold, windy and where the roads are made of rocks the size of baby’s heads.

If it wasn’t for the old heads taking the time to ride alongside young guns, to impart knowledge like a master craftsman to an apprentice, then the tribe would die out.

Cycling isn’t a Hobbesian state of nature, it’s the best example of Kropotkin’s theory: we prosper because we cooperate. Sure we get a training benefit but the reason we drive or ride to the meeting point isn’t to maximise our 20-minute normalised power, it’s to share the road and our free time with other people who share our passion.

Cycling is not a zero sum game, we all benefit from all of us getting better; the bunch ride is faster, safer, better looking. A good bunch ride, devoid of screams, surges or the slam of carbon on concrete is a great place to pick up training tips, equipment advice and, of course, the latest gossip. More than that, a good bunch ride is also a place to make and nurture lifelong friendships and to pass on the knowledge which was once passed on to you. To aid in that process of cooperation and help the species prosper.

– James Stout