He’s an innovator. But Richard Bryne is a bike rider at heart. The evolution of cycling includes input from people like him who consider notions that changed the shape of bikes and parts…

– This feature was originally published in RIDE 47 (February 2010) –

The tale of Richard Bryne and the company he founded, Speedplay pedals, is one about an 18-year-old American who travelled to the 1972 Tour de France, found himself on the front page of a French newspaper with Raymond Poulidor, returned to the States drunk with cycling fever, and spent the next two decades racing his bike and banging his head against the door of a mule-headed cycling establishment that was obstinately resistant to change.

Thinking back over the history of cycling innovators, American pro cyclist Davis Phinney says, “There’s been a few groundbreaking pioneers in this sport and Richard Bryne was clearly one of those.

“He was an innovative thinker who just kept his nose to the grindstone when the industry was not necessarily accepting of his ideas and his designs.”

Phinney knows his subject. Besides being the first American to win a stage of the Tour de France, his two-decade long racing career saw him powering the seminal 7-Eleven cycling team and finishing on the podium everywhere – the Tour, the Olympic Games, the Coors Classic. He is also father of Taylor.

Along with Speedplay pedals, Bryne invented the first aerobars and the first aero bike – a machine that is the father of the time trial bikes used in the modern era.

Jim Elliott on Bryne’s prototype aero bars during the 1985 Race Across America. The handlebars were designed to create a more aerodynamic profile and to relieve upper body strain caused by the steep tubes on new bikes he built.

Today Speedplay is ubiquitous in the pro peloton. Nearly a fifth of the 2009 Tour de France riders were pushing the lollipop-shaped pedals, and Hawaii Ironman winners Chris McCormack and Michellie Jones also use them.

From the regal cycling personalities to local striplings banging elbows in local crits, in the many years since they were first marketed the pedals have been adopted by millions of cyclists worldwide.

Bryne shows off the TurboTrainer he designed in 1981 and licensed to a San Diego manufacturer.

Based in San Diego, California, Speedplay was founded in 1991 by Richard Bryne and his wife Sharon. The affable 56-year-old was born in Venezuela to a British mother who made her way to South America to teach English and an American father who was a Gulf Oil employee.

When his parents moved to Florida, Bryne began tinkering with bicycles and motorcycles.

When he broke his kneecap in a moto wreck in 1971, his doctor encouraged him to continue cycling for rehab. That led to him entering bike races and, in 1972, travelling to France to watch the Tour.

“That was the time I really got interested in following racing,” Bryne recalls, adding that at the time it was so unusual to find an American spectator at the Tour that a French newspaper published his photo.

“They put me on the front page with Raymond Poulidor.”

The experience of viewing the Tour in person – and appearing in print with the legendary Frenchman – deeply inspired the 18-year-old.

“I really got into it once I got back and decided I wanted to pursue life as a bike racer.”

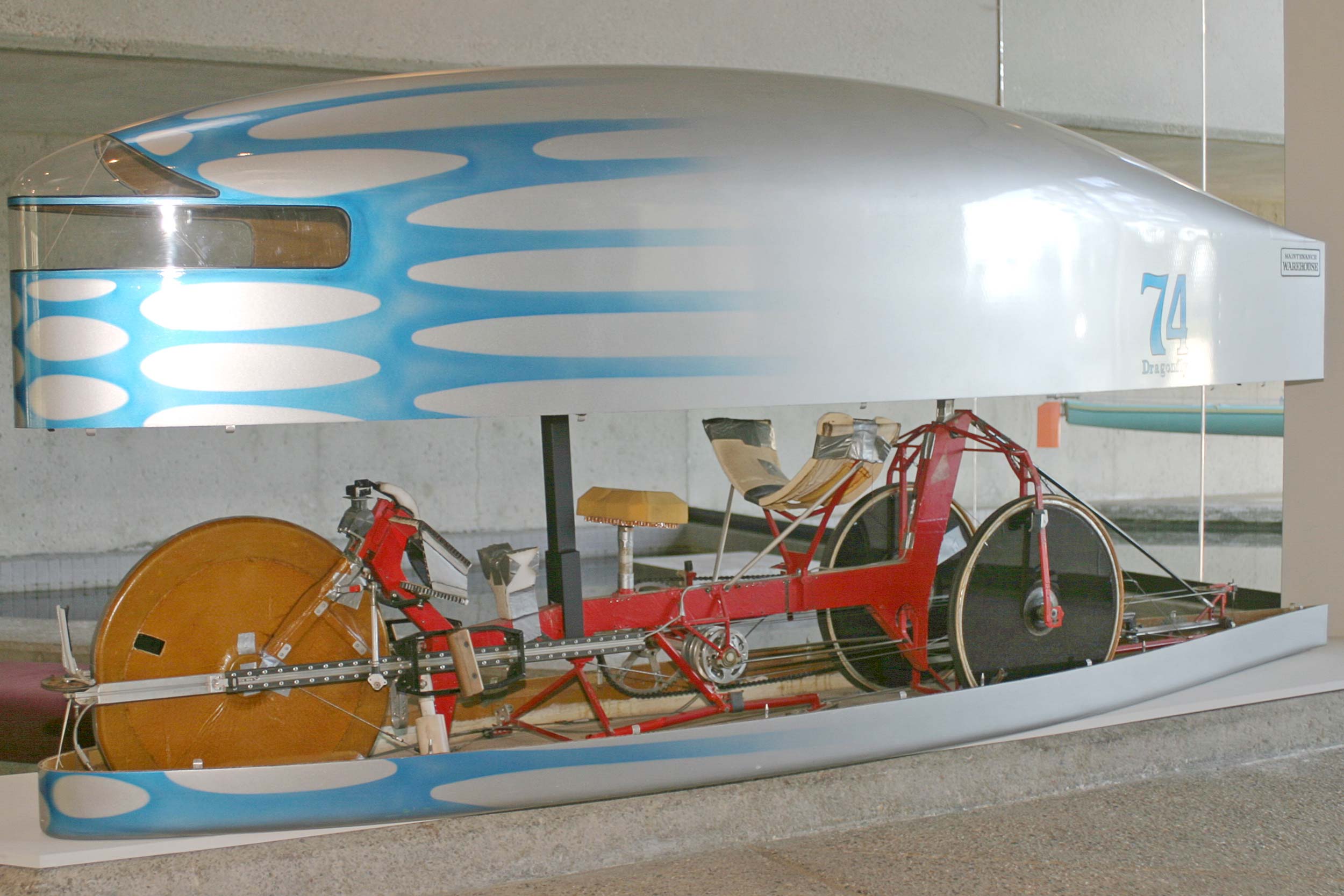

This articulated frame sizing machine was designed and built by Bryne around 1983. He called it the Ouija bike. At the time, the notion of putting a rider in a position that maximises both aerodynamic efficiency and power and then building a bike to fit that ideal position was wholly radical.

In 1975, Bryne worked his way from the east coast to California for its active racing scene. A fortuitous meeting at San Diego’s velodrome started the chain of events that led to the birth of Speedplay some 15 years later.

“I met this guy one night who had brought a human powered vehicle (HPV) to the velodrome and he was looking for a motor to race it.”

These aerodynamic vehicles used to break human-powered land speed and distance records.

Steve Ball held a rider try-out at his house and Bryne won the spot through smart thinking rather than brute force.

“He had this HPV mounted on a set of custom-made rollers with an ergometer attached to it. It had a huge flywheel on it. I think I outsmarted everybody by starting a little slower. The fastest person before me had gone 45 miles an hour on the ergometer; I ended up going 55.”

It wasn’t the last time that tactical thinking would serve Bryne well.

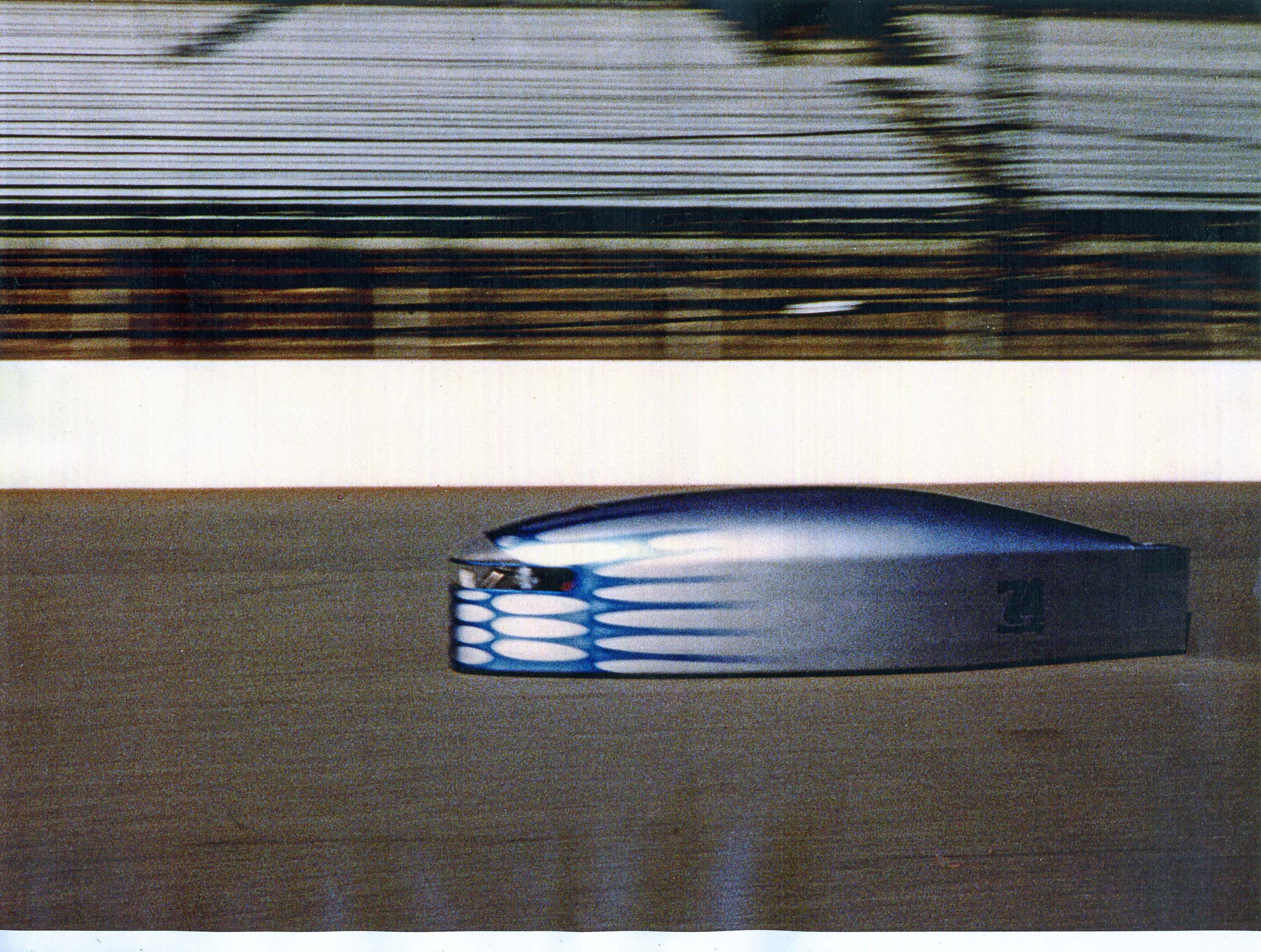

Human powered vehicles like the one that was designed by Steve Ball inspired Bryne to try new things, both on the bike and in the drawing room. In 1983 he set a speed record of 88.34km/h on the Indianapolis speedway track on the machine dubbed the ‘Dragonfly’.

Bryne raced Ball’s HPVs for six years, eventually setting a human-powered speed championship record on the Indianapolis Motor Speedway (home of the Indy 500) in 1983.

Bryne spent time hanging out where Ball made his products. That’s where he caught the bug for designing modifications that made bikes sleeker and lighter and riders more efficient.

“It was the first time I’d ever been really close to a machine and fabrication shop and seen how things were actually made,” Bryne recalls.

“I started making a few tidbits to help me with my cycling and racing. Eventually I came up with the idea for an indoor trainer so I could train at night.”

Ready to go up to full speed… The Dragonfly HPV (on the Indy track, above) was driven by both arms and legs and Byrne lay prone inside it while riding. He says he trained an hour at a time on this machine. Bryne demonstrates the training device he built to develop motion-specific fitness for his speed record ride in 1983 (below).

It’s hard to believe now, when a visit to a bike shop confronts you with a bewildering array of stationary trainer options, but at the time cyclists pretty much only used resistance-free rollers to stay supple indoors. Bryne wanted something that would allow him to concentrate on building strength and power.

He patented his invention as the TurboTrainer in 1981 and sold the concept. And thus Bryne’s career as a man who creates things that solve cycling-specific problems was born.

By attaching a fan to the base of the trainer and locking the fork to a vertical bar, Bryne introduced resistance to his indoor training regime and also solved the problem of staying upright on rollers.

“I needed something that I could just close my eyes and time trial into.”

Bryne says his device was neither the first portable trainer nor the first to use wind resistance. What made it unique was that it allowed riders to use their own bike. “It was very popular and we sold a lot of them.”

Henk Vogels was part of the Mercury team that was one of the first to use Speedplay pedals. (Photo: Graham Watson)

At this time Bryne learned the importance of lending a product credibility by getting it into the hands of experienced, respected cyclists – a lesson that would serve him later when he first got the Mercury team to use Speedplay pedals. His sponsorship coup with CSC would come later.

“I gave quite a few TurboTrainers away to my friends who were good riders. Guys like Davis Phinney and Eric Heiden and Mark Whitehead.”

When they set up their TurboTrainer at velodromes all over the US, the product was suddenly on the radar of discerning cyclists.

Bryne was getting invaluable market exposure. Soon he was cashing royalty cheques from Skid-Lid Manufacturing Company which had licensed and made the product. The cash flow allowed Bryne freedom to spend even more time riding.

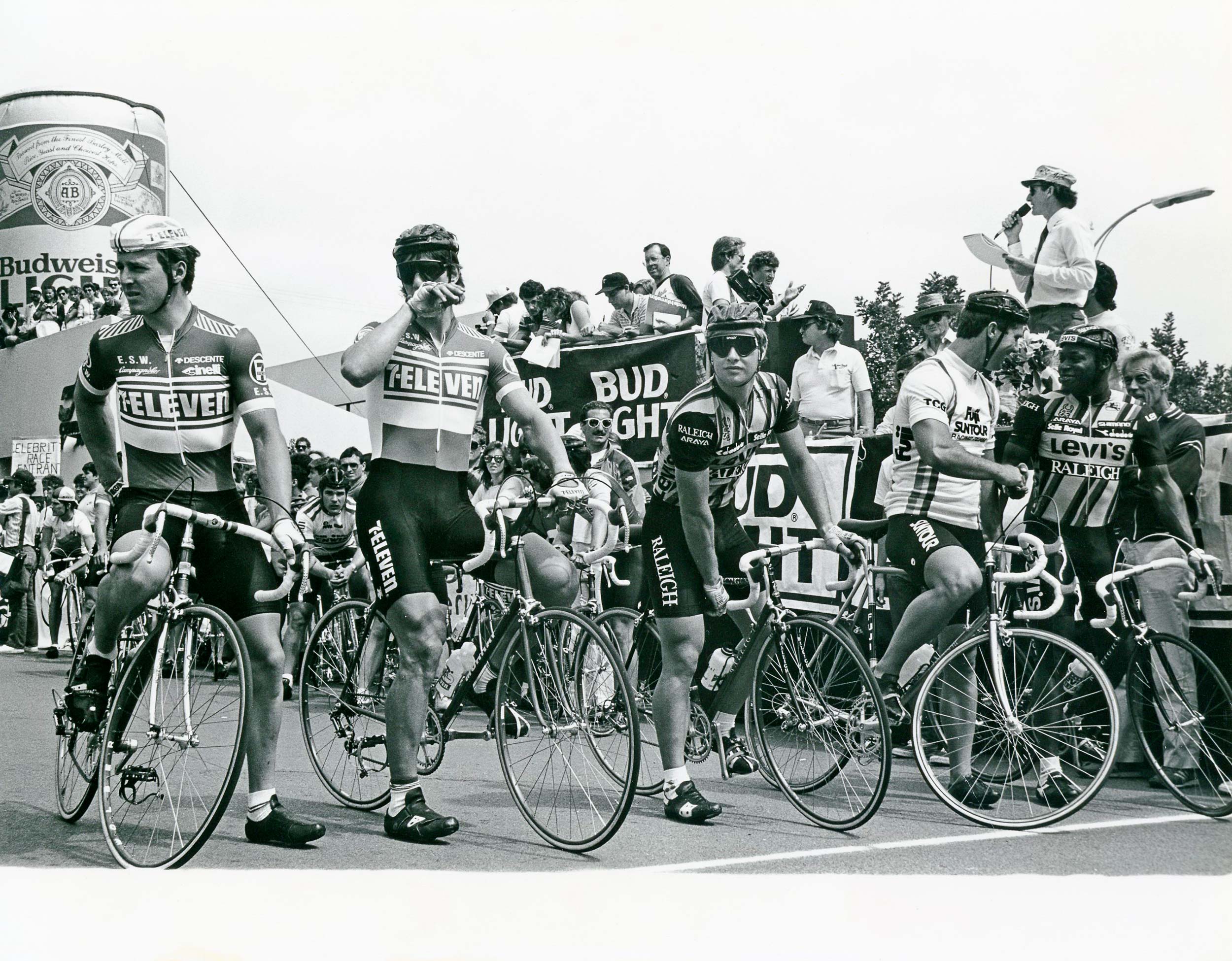

In the mid-1980s, Bryne became a race organiser and actively tried to promote the events, rather than just run them to a crowd of family and friends of the competitors. The inaugural edition of the La Jolla GP in 1985 included Olympic stars like Davis Phinney and Nelson Vails.

While Bryne is an avowed aficionado of design, he says he has only been interested in developing products that solve problems. He derives as much satisfaction out of the functional end results of a good design as the aesthetics of a beautifully crafted artefact.

Phinney’s two-generation use of the first TurboTrainer Bryne gave him is testament to the utility of the invention. “I used it a lot,” Phinney recalls. “It was my primary source of indoor training for the bulk of my career.”  Other trainers came onto the market but Phinney stuck with Bryne’s product because it worked. In fact, Phinney adds, years later he started his son Taylor out on the same trainer he used.

Other trainers came onto the market but Phinney stuck with Bryne’s product because it worked. In fact, Phinney adds, years later he started his son Taylor out on the same trainer he used.

“Richard was one of the true pioneers and visionaries when it came to giving you the ability to have a really good work-out in a really simple way. He designed it incredibly well.”

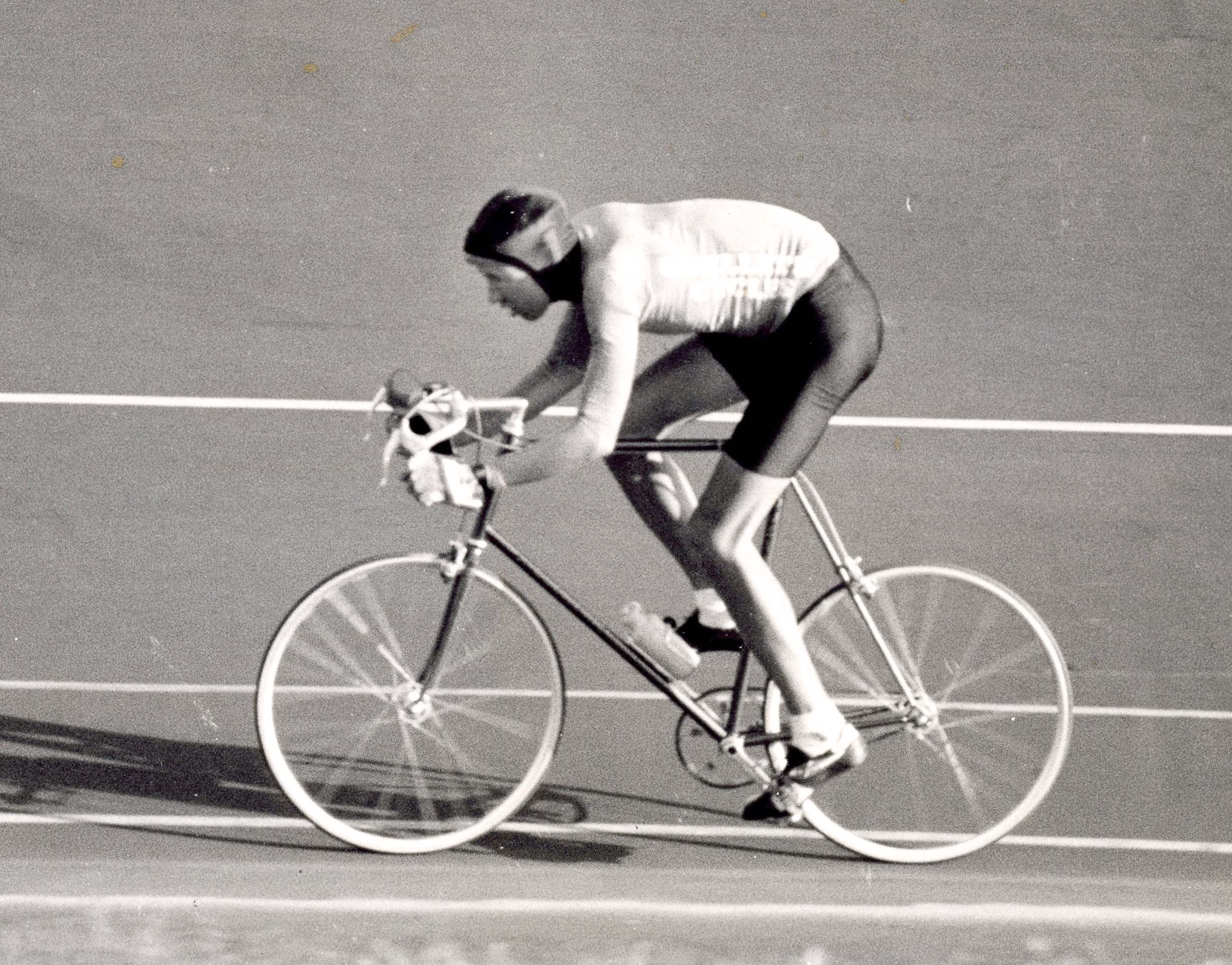

Jim Elliott on the San Diego velodrome in 1983 on his way to riding 808.3km in 24 hours on a Bryne-designed aero bike.

Bryne also branched out into coaching. His riders included 1988 and 1992 US Olympian Ken Carpenter and Mark Gorski, whom he helped to a US sprint championship in 1979 and an Olympic team spot. But the US boycotted the Games in Moscow so he never got to race in 1980, but four years later Gorski won the ‘kilo’ at the Los Angeles Olympics and went on to direct the US Postal team during Lance Armstrong’s early years of winning the Tour de France.

Bryne admits that his coaching was as much a labour of love as a source of income and that the royalty cheques from his TurboTrainer gave him a degree of financial freedom required to help others. Unlike today, few riders at the time had such support and even fewer could afford to pay for it.

Bryne’s tutoring helped him build a network with cyclists who would become instrumental in pushing the US onto the world stage during the Greg LeMond and Armstrong eras.

In the early 1980s, Bryne fell into race promotion. He found himself organising the Lemon Grove Criterium in San Diego.

“Somebody volunteered me to take over,” he recalls with a laugh. “I had about seven projects going on at the same time.”

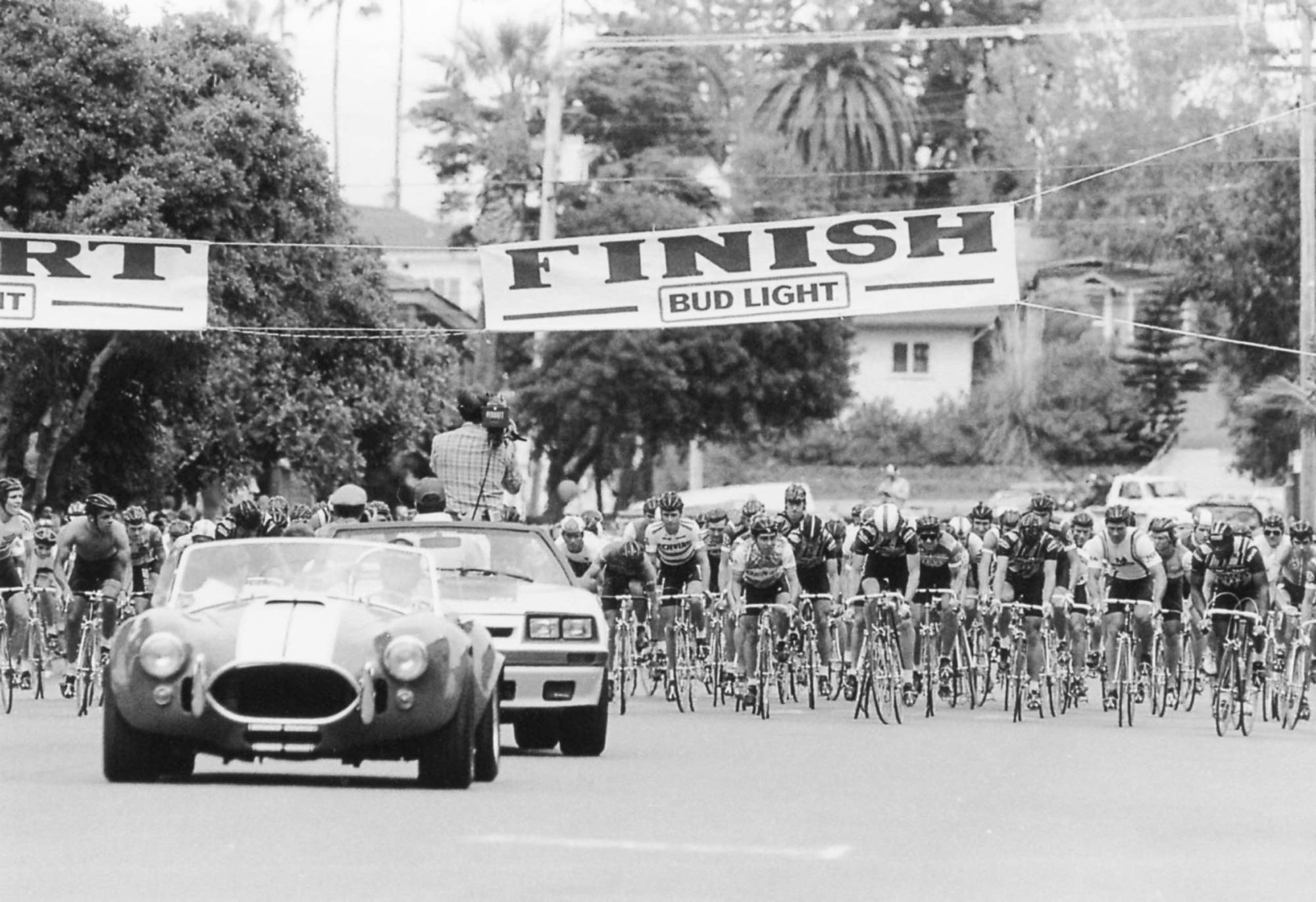

Showing his appetite for new challenges Bryne organised the La Jolla GP in 1985; this was a criterium in a wealthy seaside San Diego enclave. Perhaps more than anyone gives him credit for, that race created the template for festival-like events like the Tour of California and Tour Down Under.

When a race sponsor told Bryne he could get more people to show up to a race if he held it in La Jolla, which bristles with restaurants and designer shops, Bryne went for it. After a year of cajoling he secured permits from the hoary town fathers and the inaugural Bud Light La Jolla GP was staged.

“We had 30,000 people there the first year. We closed downtown La Jolla for the day and ran a big bike race. What was different was that traditionally races were held in industrial parks or remote areas. This one took over the town. To my knowledge, it was also the first event in the US that was completely wired for sound. I brought in a sound technician who put on rock concerts and we put a speaker system all the way around the course.”  While it seems standard for races to create a festival-like atmosphere today, in the 1970s and early 1980s promoters thought only in terms of racers, not spectators. Bryne focused on creating an event that delivered both good racing and good entertainment value.

While it seems standard for races to create a festival-like atmosphere today, in the 1970s and early 1980s promoters thought only in terms of racers, not spectators. Bryne focused on creating an event that delivered both good racing and good entertainment value.

Along with the pro race, the event featured an exotic auto show, a BMX stunt show, races for HPVs, roller bladers, and wheelchair athletes. There was a bicycle product expo, and a footrace around the crit course with triathlete star Scott Tinley and Kiwi running legend Rod Dixon.

Bob Babbitt is a San Diego-based sports promoter and publisher. He has been either participating in or reporting on endurance sports events since he raced the second Ironman triathlon in 1980. He helped Bryne organise the La Jolla GP and recalls that the racer/inventor/promoter’s cunning on the bike also translated to his business sense.

“Richard was always a tactician on the bike. He had a great reputation as a guy who knew how to win. He was always 10 steps ahead of everybody.”

Of his approach to both race promotion and his inventions, Babbitt says: “It’s not like he was doing variations on a theme. He’s the guy who is saying let’s do something that’s never been done before.”

With the La Jolla race, Babbitt feels Bryne was the first promoter to bring cycling to the masses in the States.

With the La Jolla race, Babbitt feels Bryne was the first promoter to bring cycling to the masses in the States.

In 1985, at the typical race, “you got bike racers coming out to watch bike racers, which means you have nobody. ‘So, what if I take this thing and add a little pizzazz to it and drop it in a place where people are anyway?’ He made cycling sexy.”

After seeing the seaside La Jolla race, the mayor of Redlands, California asked Bryne to help get a race going in her downtown – a stage race that carries on today. Perhaps the biggest bike festival going, California’s Woodstock-like Sea Otter Classic was set in motion when its founder, Rick Sutton, attended a La Jolla GP and saw the future of bike race promotion.

“He told me he was inspired,” Bryne recalls. “There was something for everyone.”

All of Bryne’s energies at the time were not just going into race promotion. Thanks to the aerodynamics engineers he communed with while riding the HPV, Bryne had also become fascinated by how to reduce drag on a bike. This curiosity led him to build both the first aero bike and the first aero handlebars.

“I realised that if you could make a rider more aerodynamic, you could get more speed out of them,” he recalls.

“So I started to look at ways to change the bicycle to see if I could make it more aerodynamic.”

Taking on conventional ideas… Bryne with his steeply angled Scepter bike at his San Diego, California offices. Built with frame builder Bill Holland, this was the first production aerodynamic frame and effectively the ancestor to today’s time trial bikes.

Bryne built something he called the Ouija bike. The device was an articulated bike frame that allowed him to fit a bike to a rider in an aerodynamic position. Hence the name; you could move it around like hands on a Ouija board.

In typical Bryne fashion, he scrapped unquestionable European tradition – begin with a standard road frame and make component adjustments to fit it to a rider – and started with a more practical proposition: pretzel a rider into the ideal position to reduce drag and increase power, then build a frame to fit that human form.

It’s hard to emphasise enough how upside down this idea seemed at the time.

“My idea was to forget the bicycle, put the rider in the most aerodynamic, most powerful position that I could get them in, and then build the bike so I could keep them in that position.” In the early 1980s Bryne was coaching Jim Elliot, a cyclist training for the 24-hour distance record on the velodrome. At 193cm tall, Elliot pushed a lot of air in his normal riding position.

In the early 1980s Bryne was coaching Jim Elliot, a cyclist training for the 24-hour distance record on the velodrome. At 193cm tall, Elliot pushed a lot of air in his normal riding position.

From his HPV experiences, Bryne knew that small aerodynamic changes could yield large results especially over a 24-hour period. Using the Ouija bike, Bryne found that by pushing the bottom bracket further back, he could flatten Elliot’s profile and put him into a more powerful position.

But creating a bike with a 86 to 89 degree seat tube angle wasn’t easy in steel frame days.

Lugs came in limited angles that were generally about 72 degrees – not even remotely close to the nearly vertical configuration Bryne needed.

“I had to hand-make the lugs by cutting the old-style lugs in half, changing the angle, re-welding them, filing them to fit the tubes in and then brazing it together.”

After making a bike with an 86 degree seat tube angle for himself, Bryne was astounded by the improvement in his time trial performance. He had a frame builder make a version of the aero bike for Elliott. The machine “looked crazy compared to a regular bike,” but initial tests saw a dramatic improvement in Elliot’s times.  In 1983, American Lon Haldeman was the undisputed king of ultra-distance cycling, and Haldeman owned the velodrome record of 453 miles (729km) in 24 hours.

In 1983, American Lon Haldeman was the undisputed king of ultra-distance cycling, and Haldeman owned the velodrome record of 453 miles (729km) in 24 hours.

Bryne calculated that Elliot could go 500 miles in 24 hours.

“He went on to attempt the record and, after 23 hours, he was on schedule to go exactly 500 miles. He was able to up his pace and ended up going 502.3 miles (808.4km) in 24 hours.”

With both a world record and a smashing validation of his new aero bike in hand, Bryne was inspired. “I knew I was onto something.” He called Eddy Borysewicz, a Polish coach who guided US cyclists to nine medals at the 1984 Olympics.

Borysewicz promptly dismissed the new bike design; it was to be one of many times in Bryne’s career as an inventor that cycling traditionalism trumped discoveries that made quantifiable improvements to rider performance.

Undaunted by rejection from the towering figure in US cycling, in 1984 Bryne teamed up with San Diego frame builder Bill Holland and set about making a production model of the aero bike. They sold it under the name Scepter Bicycles. Even though Bryne’s data demonstrated that his custom-fit bicycles were dramatically faster than race bikes of the time, Scepters did not sell.

Even though Bryne’s data demonstrated that his custom-fit bicycles were dramatically faster than race bikes of the time, Scepters did not sell.

“It was very difficult to sell them because they were so different than what people perceived a racing bicycle should look like. It was really an uphill battle. People just thought we were kooks.”

Phinney concurs that when it came to design evolution, the bike industry would have made a lugubrious Galapagos tortoise look nimble. “We as the road bike industry were a pretty conservative bunch.”

As an example, Phinney recalls the founder of Giro helmets Jim Gentes trying to generate interest in his new hard-shell helmet at a trade show in the mid-1980s. Phinney recounts the episode in a tone that drips with astonishment at the narrow-mindedness of the times: “We were just like, ‘What do we need that for? We’ve already got hair nets. That looks dorky.’”

Phinney (with Andy Hampsten and Raul Alcala in the 1988 Giro d’Italia, below) was one of Bryne’s original supporters. The father of 2009 individual pursuit world champion used the TurboTrainer when it was first released in 1981 and even passed it on to his son, Taylor, when he started his racing career…

Even today – when Giro’s products are de rigueur, making helmetless riders the dorks, and you can drop $15,000 on a time trial bike that is a direct descendant of the Scepter – Bryne feels cycling is still resistant to change.

“Being an inventor in the road bike world is probably the biggest challenge ever.”

What saved the sport from its inherent conservatism, Bryne holds, is triathlon. “Traditional cycling people want things to be the way they were when their grandfather rode.

“Triathletes were not tied to tradition at all. All they wanted was speed. They wanted things that were lighter. They wanted things that were faster. Almost all the innovations that came into cycling came in through triathlon.”

Bryne also faced challenges when he introduced the world to the first aerodynamic handlebars.

While Boone Lennon is usually cited as the father of aero bars, he was, in fact, the first person to patent them – doing so in 1987 and licensing them through Scott bicycles. Yet Bryne had already introduced the world to the idea in 1984, when his 24-hour record cyclist Jim Elliot had a go at the Race Across America.

One of the things that the team learned during Eliott’s 24-hour effort was that because it shifted the rider’s weight forward over the front wheel, the aerodynamic design was both uncomfortable and stressful on the arms and hands.

“My goal was to make something special for the Race Across America which is essentially a 3,000-mile time trial.”

Eventual 1984 Race Across America winner Pete Penseyres catches a glimpse of Jim Elliott’s newfangled aero bars during their first RAAM use.

Working with a Massachusetts frame builder, Bryne designed a bike that used both the Scepter’s frame geometry and narrow aero bars that had never been seen in public. Because he had not patented the bars, he was paranoid about showing them at the RAAM start in Los Angeles.

Elliot started the race on a traditional racing bike. After keeping a short leash on perennial winner Lon Haldeman for the first few hours of the race, Elliot swapped mounts in the desolate high desert north-east of Los Angeles.

“When we got out to Baker, California we switched bikes and put Jim on the new secret weapon, and it was the first bike to use aero bars.

“We cruised right past Haldeman and we were the first to reach Las Vegas. It was the first time anyone had beaten Haldeman out of California, so we knew we were off to a great start.”

Alas, Elliott suffered several epileptic episodes during that race and the team eventually finished fourth.

Asked why Boone Lennon gets credit for aero bars, Bryne says he made the mistake of trying to sell them before he patented them. A full five years before LeMond vaulted aero bars into the public consciousness by using them to dramatically win the 1989 Tour de France in the final time trial, Bryne’s bars had been tried and proven in competition.

“I tried to sell them and no one would buy them,” Bryne recalls.

Bryne holds no grudge against Lennon for filing his patent first. The experience did not make him bitter, but wiser. “The only claim I can make is that I used the bars in competition before anybody.” Along with that, he takes satisfaction in knowing he “was able to make fundamental improvements to the bicycle that it’s taken 20 years before they became adopted by the greater cycling community.”

With two certifiably groundbreaking products rejected by the industry, one would think Bryne would have said to hell with continuing as a bike inventor. His grit and drive didn’t allow that to happen. As the 1980s were coming to a close Bryne was busy promoting races. “But,” he says, “I longed to get back into the bike business. I kept thinking there’s got to be something I can improve on. ”  Bryne had ridden clipless pedals since the 1970s when Cinelli released the M71. In 1983, Keywin clipless pedals came out of New Zealand but it wasn’t until 1984 that Look’s ski binding-inspired pedal had widespread commercial success.

Bryne had ridden clipless pedals since the 1970s when Cinelli released the M71. In 1983, Keywin clipless pedals came out of New Zealand but it wasn’t until 1984 that Look’s ski binding-inspired pedal had widespread commercial success.

Bryne is a dedicated collector of historical cycling artefacts and has a fascinating pedal history photo exhibit on the Speedplay website.

“They were all big and thick and sort of clunky and some were hard to get into,” said Bryne of these first-generation pedals.

“I just thought there’s got to be a better way to do it.”

As a racer he had always been looking for ways to make bikes lighter. Babbitt recalls Bryne spending hours drilling holes in his bikes and components to trim every possible gram. In 2000, a Popular Mechanics magazine article describes Bryne’s assembly of the world’s then-lightest 11.3 pound bike.

It came to Bryne that the best way to solve these problems of weight and usability was to make the pedal double-sided “so you wouldn’t have to look down to clip in”.

The result of his brainstorming and prototyping is today’s Speedplay pedal. “When I came up with the lollipop idea I thought, someone has got to have thought of this. But nobody had. I was lucky. It was really a simple thing, but sometimes it’s the simple things that people don’t think of first.”

“When I came up with the lollipop idea I thought, someone has got to have thought of this. But nobody had. I was lucky. It was really a simple thing, but sometimes it’s the simple things that people don’t think of first.”

Bryne filed for a patent and prototyped the pedal. With palpable delight, he recalls his first time riding the prototype: “I rode it and I know it was the hottest thing around. It was lighter, it had better cornering clearance, had lower stack height, it was twice as easy to get in, you couldn’t pull out in a sprint – it had all of the advantages that I wanted and none of the disadvantages.”

Bryne started shopping the prototype around to manufacturers and got a familiar reception – rejection.

“We took it around to as many people as we could to try and pitch the idea to see if we could license it.”

A total of 22 companies turned down the newfangled pedals.

Rather than falling back to race promoting and coaching again, this time Bryne started a company on his own. He received a patent in 1989, rounded up early investors and the company was officially organised in 1991. The name Speedplay comes from the Swedish interval work-out term fartlek – speed play.

Getting the pedals accepted was an uphill tussle. Bryne reflects on his initial efforts to get the bike industry to warm to his new product: “It was so freaky to most people when they saw it that I was basically in the same world I was in before.

“I just couldn’t get people to wrap their heads around the idea that this was a bicycle pedal because it looked so different from what people had imprinted in their head. It took a long time before people took us seriously.”

Sponsorship of pro teams like Saxo Bank has helped Richard Bryne gain credibility for his company’s products. Triple world champion Fabian Cancellara used Speedplay pedals for years and the system has gained mainstream acceptance.

Bryne learned how association with known cyclists could lend a newfangled product credibility and shift it from the freaky to the cool category. Once he got his TurboTrainer into the hands of riders like Davis Phinney it became an acceptable, if not required, possession among change-wary racing cyclists.

“One of the things that I learned real quickly is that you can’t just have a better product. You have to have a product that’s validated by people that people respect.”

Photo: Graham Watson

To get his weird-looking pedals established with the cycling orthodoxy, Bryne set about getting them beneath the feet of the best racers he could find. Of course, a Yankee doesn’t just square dance into a European pro team’s configuration and get them to start using his product, no matter how great a problem it solves.

“It’s easy to be locked out by bigger companies because they can offer full groupsets,” explains Bryne, “and they can prevent you from getting in. It actually takes a lot longer than you’d imagine to get to the top level. You have to pay your dues.”

Speedplay started out sponsoring small US pro teams. They then had the good fortune to sponsor Mercury which by 1999 and 2000 – the years Floyd Landis and Henk Vogels joined the squad – had grown into a dominant team on the US pro circuit. Next, Speedplay got on board with CSC when they were ranked a lowly 14th in the world.

“We rode that wave,” Bryne notes with pride of his association with the rise of the team from middling to powerhouse. “By the time they were number one, we were flying.”

He adds that CSC’s success lifted all the sponsor boats. “The other marketing partners who had started with us were all doing well, because we were working together to make the best bikes and equipment we could.”

In 2009, Speedplay sponsored four ProTour teams as well as some of the world’s top pro triathletes.

Jumping to 2010, Bryne was optimistic that five Tour de France teams would be using Speedplay pedals – one quarter of the peloton. Reflecting on his ride from promoting dinky criteriums in dusty San Diego county corners to spending his days flying around the world consulting with Saxo Bank, Liquigas, Cervélo TestTeam and other big-time players, Bryne says: “It’s been really fun. We really love racing. It’s in the DNA from the riding, the promoting and the product side.”

In 2010 [when this article was originally published] Speedplay was a tightly held private company with 31 employees that sells its mountain and road pedals in almost every global cycling market.

* * * * *

According to Richard, Sharon also has a better eye for up-and-coming triathlon and cycling talent. This combination of her sense for rising stars and her connections in the industry has helped more than one aspiring young rider land a ProTour contract.

“She pays much closer attention to race results than I do and remembers names a lot better than me,” Bryne admits.

By having Sharon’s ear so close to the ground, Speedplay can approach riders with sponsorship proposals before the rider or their agents come knocking on Speedplay’s door.

As for measures of Speedplay’s profitability and income, Bryne keeps numbers close to the vest. However, he does let on that they are growing at a 10 to 20 per cent rate even in the midst of a recession. “In 2009 we had a fantastic year.”

Perhaps long-time Speedplay observer Bob Babbitt best summarises the story of a determined 18-year-old who returned from the Tour de France in 1972 and turned his passion into a company that continues to grow.

“Richard was always right in everything he looked at and analysed: ‘I wonder if handlebars should be different? What would happen if we put somebody on a steeper seat tube? What would happen if we made the pedals smaller and lighter and round?’ He is pragmatic and he is a problem solver in everything he does.”

– By Mark Johnson

– For more: #CyclingParaphernalia and #BikeGalleryByRIDE –