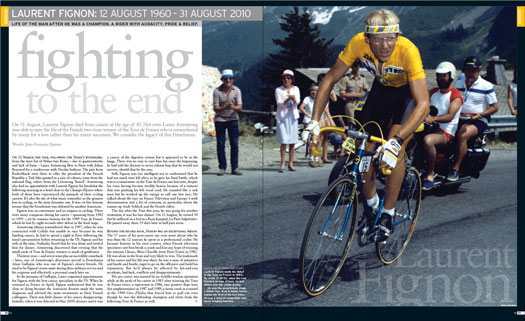

Laurent Fignon: 12 August 1960 – 31 August 2010

Life of the man after he was a champion. A rider with audacity, Pride & belief.

On 31 August, Laurent Fignon died from cancer at the age of 50. Not even Lance Armstrong was able to save the life of the French two-time winner of the Tour de France who is remembered by many for a loss rather than his many successes. We consider the legacy of this Frenchman.

On 22 March this year, following the Texan’s withdrawal from the start list of Milan-San Remo – due to gastroenteritis and lack of form – Lance Armstrong flew to Paris with Johan Bruyneel for a rendezvous with Nicolas Sarkozy. The pair from RadioShack were there to offer the president of the French Republic a Trek bike painted in a mix of colours, some from the national flag, others from the Livestrong ‘brand’. Armstrong also had an appointment with Laurent Fignon for breakfast the following morning in a hotel close to the Champs-Elysées where both of them have experienced the pinnacle of their cycling careers. It’s also the site of what many remember as the greatest loss in cycling, or the most dramatic one. It was on this famous avenue that the Frenchman was defeated by another American.

Fignon was an entertainer and an enigma in cycling. There were many conquests during his career – spanning from 1982 to 1993 – yet he remains famous for the 1989 Tour de France which he lost by eight seconds after defeat in the final stage.

Armstrong always remembered that in 1997, when he was contracted with Cofidis but unable to race because he was battling cancer, he had to spend a night in Paris following the team’s presentation before returning to the US. Fignon and his wife at the time, Nathalie, heard that he was alone and invited him for dinner. Armstrong discovered that evening that the small circle of Tour de France winners is made of gentlemen.

Thirteen years – and seven wins plus an incredible comeback – later, one of Armstrong’s directeurs sportif is Frenchman Alain Gallopin who was one of Fignon’s closest friends. He used to be Fignon’s team-mate during their military service and his soigneur and effectively a personal coach later on.

In the presence of Gallopin, Lance organised appointments for Fignon with the best cancer specialists in the US. When he returned to France in April, Fignon understood that he was close to dying because the American doctors made the same diagnosis and advised the same treatments as their French colleagues. There was little chance of his cancer disappearing. Initially, when it was detected in May 2009, doctors said it was a cancer of the digestive system but it appeared to be in the lungs. There was no way to cure him but since the beginning, he had told the doctors to never inform him that he would not survive, should that be the case.

Still, Fignon was too intelligent not to understand that he had not much time left alive, so he gave his final battle, which was to commentate on the Tour de France one last time, despite his voice having become terribly hoarse because of a tumour that was pushing his left vocal cord. He sounded like a sick man but he worked up the energy to call one last race. He talked about the race on France Television and Europe 1 with determination and a lot of criticism, in particular about the runner-up Andy Schleck and the French riders.

The day after the Tour this year, he was going for another treatment; it was his last chance. On 12 August, he turned 50 but he suffered on a bed at a Paris hospital, La Pitié-Salpêtrière. He passed away there 19 days later at half past noon.

Beyond the record book, Fignon was an exceptional person. The 17 years of his post-career say even more about who he was than the 12 seasons he spent as a professional cyclist. He became famous in his own country when French television spectators saw him break a crank and lose any hope of winning the autumn Classic, Blois-Chaville (now Paris-Tours) in 1982. He was alone in the front and very likely to win. The trademark of his career and his life was there: he was a man of initiatives and hustle and bustle, eager to go on the offensive and build his reputation. But he’d always be affected by hit-and-run accidents, bad luck, conflicts and disappointments.

His pro career was marred by an Achilles tendon operation while at the peak of his career in 1985 after winning the Tour de France twice, a tapeworm in 1986, two positive dope tests (for amphetamines) in 1987 and 1989, a nasty crash in a tunnel at the 1990 Giro d’Italia that forced him to pull out even though he was the defending champion and retire from the following Tour de France as well.

When he concluded his career at the end of 1993, he was sick of cycling. Although he didn’t mind taking the available drugs of his time in the 1980s, once upon a time, as he explained in his biography ‘We Were Young and Carefree’, he had refused the EPO he was offered at his Gatorade-sponsored team in the last two years of his career. During his time on the Italian squad he realised this sport was badly affected by a new form of cheating: blood doping.

He was sick of the narrow-minded members of the cycling community as well. Recently retired, he decided to travel, to take part in the adventure of the Raid Gauloises in South America and he found a new passion: playing golf. Quickly, he got bored of all that and wondered, “What could I do that would drive me with the same level of passion as competitive cycling at the highest level?” He was not a man who would accept invitations for being the guest of honour at cycling events, or gather with the old greats at banquets to remember the good old times. He was a man of action! A natural fighter, he was destined to become an event organiser. He was never afraid of handling responsibilities.

As early as in 1995, he had the idea to take over from Josette Leulliot as the director of Paris-Nice. A fight against the monopoly of the biggest promoter, ASO, was a natural fit for Fignon but the daughter of the founder of ‘the race to the sun’ wasn’t yet keen to sell her business. Therefore, Fignon set his sight on fun rides, xpredominantly for wealthy cyclists.

He was full of ideas to develop cycling in general. He wasn’t short of cash but wouldn’t mind earning some extra money as he realised mass cycling could eventually be a lucrative proposition. With Gallopin and a couple of associates, he placed barricades along roadsides and drew routes in the region of Ile-de-France, the department that has Paris at its core. But the double winner of the Tour de France was definitely not in his normal universe with leisure cyclists.

“Me! To be insulted because I didn’t sweep the ground? No thanks,” he said when he gave up after two years of organising these rides in prestigious venues. “I wasn’t gonna work all my life for guys who just don’t want to respect the highway codes while riding their bikes!”

Professional cyclists also didn’t respect all the codes as they doped so much in the 1990s – the EPO years – so the timing wasn’t exactly the most favourable when Leulliot eventually accepted an offer for Paris-Nice. It was in 1999, just one year after the Festina Affair struck – a time when sponsors were reluctant to invest in cycling. To become a race organiser, Fignon was prepared to pay from his own pocket. “Do you know many cycling champions who invest the money they won on the bike to help make the next generation race?”

It was typical Fignon: harsh, honest, and caustic with sarcasm. He added more insults with his appraisal. “There are plenty of former riders who ask for a job as a chauffeur!”

Fignon organising the 57th edition of Paris-Nice in 2000 was like the rekindling of a tradition. As he commentated bike races for Eurosport in the 1990s – something he’d do again for the Belgian broadcaster RTBF in 2004 and, eventually, for France Television from 2006 until a month before his death – he conceived ‘the race to the sun’ so that it would be good to watch and talk about during the coverage on television.

The legendary promoter and director of the Tour de France from 1936 to 1986, Jacques Goddet, designed his race routes in order to make the race compelling and interesting enough to write about in newspapers. Similarly, the current Tour director Christian Prudhomme found that he used to get a little bored doing his previous job, commentating on bike races for television. He now looks for routes that are likely to create movements in the race.

The 2000 Paris-Nice provided a relaunch of the career of Laurent Brochard after the Festina Affair. The Frenchman won the prologue and finished second overall behind a young revelation – and future runner-up to Armstrong at the Tour de France – Andreas Klöden. The course was full of subtleties, like the feedzone sometimes located at the bottom of a hill to give incentive to the riders eager to forsake their musette and attack instead of opting to take on food.

The atmostphere surrounding cycling was not one of enthusiasm after the Festina Affair. But Fignon gave the true cycling lovers something to help them believe in their sport again. Unfortunately, the 2000 Paris-Nice was organised without sponsors. And it was not only because cycling was not attractive in the publicity stakes: Fignon’s personality was another reason why sponsors didn’t come on board. “Some company directors accepted to meet me but although they knew they’d never sponsor my race, they took the opportunity to get to know me in person as a celebrity,” he realised.

One of his apparent potential sponsors welcomed him saying, “I recognised you! You’re the guy who lost the Tour de France for eight seconds!”

Fignon’s response was frosty. “You’re totally wrong. I’m the guy who won it twice.”

*****

Laurent Fignon was so proud of his achievements as a champion cyclist that he hardly accepted the idea that big companies wouldn’t necessarily adhere to his projects as a race organiser. When he had an appointment, he got pissed off if he had to wait. During his days of glory as a racer, he amazed the people with his punctuality. While journalists, for example, normally had to wait for riders to have finished their dinner or their massage, Fignon was always ready for the interview at the exact time agreed.

In public Fignon was often cranky, but in a small circle he was talkative, creative, interesting and even friendly when he described his races and his cycling world. However, he remained puzzling because anyone who thought they had broken the ice with Fignon would discover a block of ice had reformed a day later. His friends say that was a result of him being shy.

“I’ve understood that looking for money wasn’t my forte, but organising… I like that for sure,” he admitted after a couple of failures. But he always persisted. He was full of ideas. He loved the roads of the Limousin region in the centre of France and launched a short stage race called Paris-Corrèze in 2001. That was during the time Jacques Chirac was the French president, when many decisions for the country were taken in the Corrèze province where he used to be elected by the farmers. It’s a very traditional, rural area and quite different from Fignon’s Parisian origins.

In Corrèze, he teamed up with Max Mamers, a former race car driver, a record holder for a lap at the 24 Hours of Le Mans, and now an organiser of different events. Had Fignon met Mamers earlier, he might not have failed in the organisation of Paris-Nice, but after only two editions of the week-long event contested in March each year, he was forced to sell the race to ASO. He regretfully did this and cashed in 300,000 euros less than what he had paid for it but, in typical style, he didn’t just do the business. He also threatened to not sell any more and publicly accused ASO representatives of being dishonest, something he later apologised for after he eventually met Patrice Clerc, the ASO president at the time.

But in reality, he took some revenge as he had a personal issue with Daniel Baal, the former president of the French Cycling Federation. Baal was the director of cycling at ASO prior to being replaced by Prudhomme while general director of ASO and now retired Jean-Marie Leblanc opted not to conduct any negotiation directly with Fignon. Both Baal and Prudhomme did not respect each other. The reason for this is complex but some of it stemmed from Fignon’s time as a rider when Leblanc – as a journalist – suggested in L’Equipe that the knee operation he needed was a consequence of doping substances he abused.

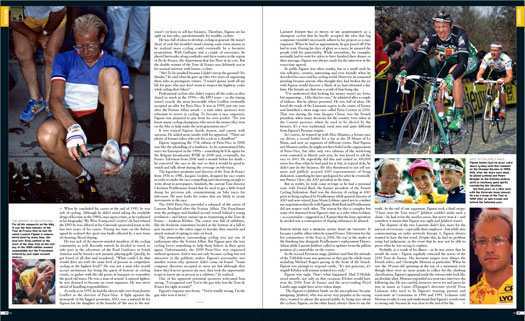

Fignon never had a problem saying what he thought. It became a public affair when he joined France Television for the live commentary of the Tour in 2006. He was in the studio at the finishing line alongside Prudhomme’s replacement Thierry Adam while Laurent Jalabert called in updates from the pillion position of a motorbike on the course.

In the second Pyrenean stage, Jalabert said that the attitude of the T-Mobile team was generous as they got the whole team including Michael Rogers pacing at the front of the bunch. Fignon was prompt to respond curtly, “It’s not generous, it’s stupid! Klöden will remain isolated too early.”

Fignon was right. That’s what happened. Had T-Mobile raced smartly, not only on that occasion, Klöden would have won the 2006 Tour de France and the never-ending Floyd Landis saga might have never taken shape.

The Fignon-vs-Jalabert battle on the microphones became intriguing. Jalabert, who was never very popular in his racing days, wanted to please the general public by being nice about the cyclists. Fignon, on the other hand, always chose to say the truth. At the end of one argument, Fignon took a final swipe: “I have won the Tour twice!” Jalabert couldn’t make such a claim – he had worn the maillot jaune, but never won it – and somehow it meant that Fignon was right and Jalabert wasn’t.

The disputes of the two Laurents didn’t last, more for the interest of everyone – especially their employer – but while also commentating on radio network Europe 1, Fignon always wanted to have the last word. Despite this, he had no problem using bad judgement, in the event that he may not be able to prove what he was trying to explain.

Probably as a result of his illness – as he was aware that he would die soon – Fignon regularly criticised the actors of the 2010 Tour de France. His favourite targets were always the French riders, and Christophe Moreau in particular. When he saw the 39-year-old sprinting at the top of a mountain even though there were no more points to collect for the climbing classification, Fignon’s appraisal made the veteran rider look like an absolute idiot. Moreau responded in a post-race interview the following day. He was careful, however, not to try and prove he was as smart as Caisse d’Epargne’s directeur sportif Yvon Ledanois who used to be Fignon’s training partner and team-mate at Castorama in 1990 and 1991. Ledanois told Moreau to take it easy and understand that Fignon’s words were so strong only because he was close to the end of his life.

As a fighter himself, one who never exchanged any gift with Bernard Hinault or Greg LeMond, Fignon did not appreciate Andy Schleck and Alberto Contador being so polite to each other. He was terribly critical of Schleck when, as the wearer of the yellow jersey, he went back to his team car to collect bidons for himself and his team-mates. Fignon was adamant that it was a loss of energy and he’d pay for it later. Others in the convoy noted that the race was going very slow at that time, suggesting that it wouldn’t harm the race leader who had found a way to look friendly in doing what he did. He illustrated that he never took the role of team captain too seriously.

After the microphones were switched off, Thierry Adam told Fignon he was maybe a bit harsh with his criticisms. The former Tour de France champion answered him, “Oh Titi, it’s okay! Possibly in one month from now, I’ll be dead.”

One month, that’s the remaining time he had to be alive after giving his final fight: the 2010 Tour de France. Laurent Fignon knew the cancer was unlike any cycling champion he rode against: it was unbeatable.

– Jean-François Quenet

Fignon’s racing record…

Nine months after he broke a crank in front of a huge number of television viewers in the finale of Blois-Chaville that he was probably going to win in 1982, Laurent Fignon was not named as a favourite for the 1983 Tour de France despite the absence of his team captain from Renault-Elf, Bernard Hinault.

His debut as a pro was quite exceptional though, with a win at the Criterium National (now International) and a 15th place overall plus second in stage three at the Giro d’Italia which he rode at the service of Hinault. In 1983, he was again learning his job at Hinault’s side at the Vuelta a España – won for the second time by ‘The Badger’. Fignon finished seventh overall in Spain, won stage four and got two second and third places.

On the day of Fignon’s death, the first images that appeared on Spanish television – without any commentary – were those of the early days of his glory in Spain. It’s not only in Italy that he was remembered with respect although it’s in Italy that he was first given the nickname Il Professore – The Professor.

Seventh in the Vuelta (contested in April at the time) was still not enough for Fignon to be ranked among the favourites of the Tour, for the Peugeot team was considered the one to beat. It had an Anglo-Saxon contingent made up of Phil Anderson, Robert Millar, Allan Peiper and Sean Yates but it was their French team-mate Pascal Simon who took the yellow jersey that he later had to surrender because of a broken shoulder. This episode was an emotional one and in the eyes of the public, Fignon ‘received’ his first yellow jersey rather than ‘earned’ it. However, he didn’t lose against the best climbers and won the final TT in Dijon the day before celebrating his first Tour de France overall victory in Paris.

In 1984, Fignon proved that he didn’t only win the Tour de France because Hinault wasn’t there. He should have won the Giro d’Italia that year but a combination of Italian forces made Francesco Moser a winner. It was a fiasco with mountain stages being cancelled by race organiser Vincenzo Torriani and a helicopter helping out the world hour record holder at the time in the final time trial to Verona. It didn’t break Fignon’s morale though as he dominated Hinault, who had become his adversary after joining the La Vie Claire team.

The Badger reacted with pure pride and attacked at the base of Alpe d’Huez. “He made me laugh,” Fignon stated right after the stage, and that was the beginning of a misunderstanding between the French public and him. He had tarnished the image of the great Hinault and he would pay for the comment. Never mind that Fignon beat Hinault in that Tour de France by more than 10 minutes! It was absolute domination by the arrogant young Parisian. A blond with glasses who looked like an intellectual had dared to outclass the Breton farmer.

Dark years followed Fignon’s glory. In 1985, he required surgery for an Achilles tendon before mounting a successful comeback in 1986 by winning la Flèche Wallonne but pulled out of the Tour that July in Pau, the same place where Hinault quit in 1980. In 1987, he finished third overall in Paris-Nice and the Vuelta a España and also won the stage to La Plagne at the Tour. He was more remembered, however, for losing nine minutes to Jean-François Bernard in the uphill TT to Mont Ventoux and he was passed in the GP des Nations time trial by his team-mate at Système U, Charly Mottet, who started eight minutes behind and finished four minutes ahead!

In the mid-1980s, when cycling teams became more of a business and Hinault was destined for La Vie Claire, set up by the adventurous French businessman Bernard Tapie, Fignon became the first champ to own his own team, in conjunction with directeur sportif Cyrille Guimard. They sold space on the jerseys to Système U and Castorama but those sponsors didn’t enjoy as much success as Fignon promised.

He won Milan-San Remo twice though (in 1988 and 1989), and that second win signalled another restart for his career. This was arguably his best year. He finally won the Giro and should have won the famous duel against his former team-mate Greg LeMond at the Tour de France. It was the battle of two champions who had returned to peak condition and the yellow jersey kept going from one to the other. In the Alps, Fignon had taken the advantage and enjoyed a lead of 50 seconds prior to the final time trial from Versailles to the Champs-Elysées that celebrated the 200 years of the French Revolution on a 24.5km course. As the Frenchman lost only 56 seconds to the American on the 73km course from Dinan to Rennes on stage five, he thought he was fine… but he had a saddle sore aerobars was used by his rival. Eights seconds went missing and Fignon failed to win his third Tour de France. That made him more famous than anything else he did in his life.

Ironically, later that year, Fignon was denied the start at the GP Eddy Merckx because the aerobars he had subsequently adopted were declared illegal by the commissaires.

But it didn’t take him long to come back from his devastation after losing the Tour. He went on training rides behind Alain Gallopin’s scooter and was fit for the world championships in Chambéry which was contested one month after the Tour. He attacked in the Côte de la Montagnole although his compatriot Thierry Claveyrolat had a good chance to win had his lead group stayed away. Fignon, however, considered that he should not have to share the leadership with anybody else. Ah, then LeMond came across and crucified Fignon once again!

Fignon was never as competitive after that. In 1990, he went to defend his Giro title but crashed in a tunnel and was forced to pull out a few days later because of a micro-fracture above his knee. The same problem made him abandon the Tour de France as well. The next year heralded his separation from Cyrille Guimard, who favoured another Castorama rider, Luc Leblanc, at the Tour de France, where Fignon still finished sixth and proved that he wasn’t definitely done.

He secured his most lucrative contract with Gatorade as a team-mate of 1991 Tour de France runner-up Gianni Bugno. Fignon won stage 11 at the 1992 Tour de France for the Italian squad but his good days were over and EPO made other riders stronger than him. He was sick of cycling when he retired at the GP Plouay in 1993 at the age of 33 after winning three Grand Tours and Milan-San Remo twice.

– Jean-François Quenet

For regular updates from RIDE Cycling Review, be sure to “Like” us on facebook.com/RIDECyclingReview