The #RandomBikeGallery on RIDE Media’s Instagram account continues to grow and occasionally a bike pops up that deserves a little more attention. A fine example is the Clamont track bike built for Martin Vinnicombe by Australian craftsman, Geoff Scott, in 1986.

– This story was first published in #RIDE57 (September 2012) –

With a Columbus steel frame, ‘cow horn’ handlebars, double disc wheels – the front smaller than the rear – and a construction based on a design by Cinelli, the Clamont bike Martin Vinnicombe raced on provides a look back in time.

With a Columbus steel frame, ‘cow horn’ handlebars, double disc wheels – the front smaller than the rear – and a construction based on a design by Cinelli, the Clamont bike Martin Vinnicombe raced on provides a look back in time.

“It’s really quite ridiculous that we thought we could go fast…” — Martin Vinnicombe

There are few people as opinionated and outspoken as the ‘kilo’ world champion from 1987, Martin Vinnicombe. As a 22-year-old, he was the pin-up boy of Australian cycling and he competed in the Seoul Olympics, finishing second in the 1,000m time trial behind Aleksandre Kiritchenko.

There are few people as opinionated and outspoken as the ‘kilo’ world champion from 1987, Martin Vinnicombe. As a 22-year-old, he was the pin-up boy of Australian cycling and he competed in the Seoul Olympics, finishing second in the 1,000m time trial behind Aleksandre Kiritchenko.

Vinnicombe had sponsorships with companies like Lucozade that ran ads on television using his image as the selling tool… at a time when track racing had far more exposure than road cycling in Australia.

But in 1991 his world came tumbling down; a positive result for Stanozolol from an out-of-competition test while he was living in Trexlertown, Pennsylvania ended his career.

He admitted to using the steroid and never raced a bike again.

Twenty-one years later, in 2012 (when this story was originally published) he operated a farm in Tasmania with produce as diverse as saffron, blackwood – “for furniture” – hazelnuts and even truffles.

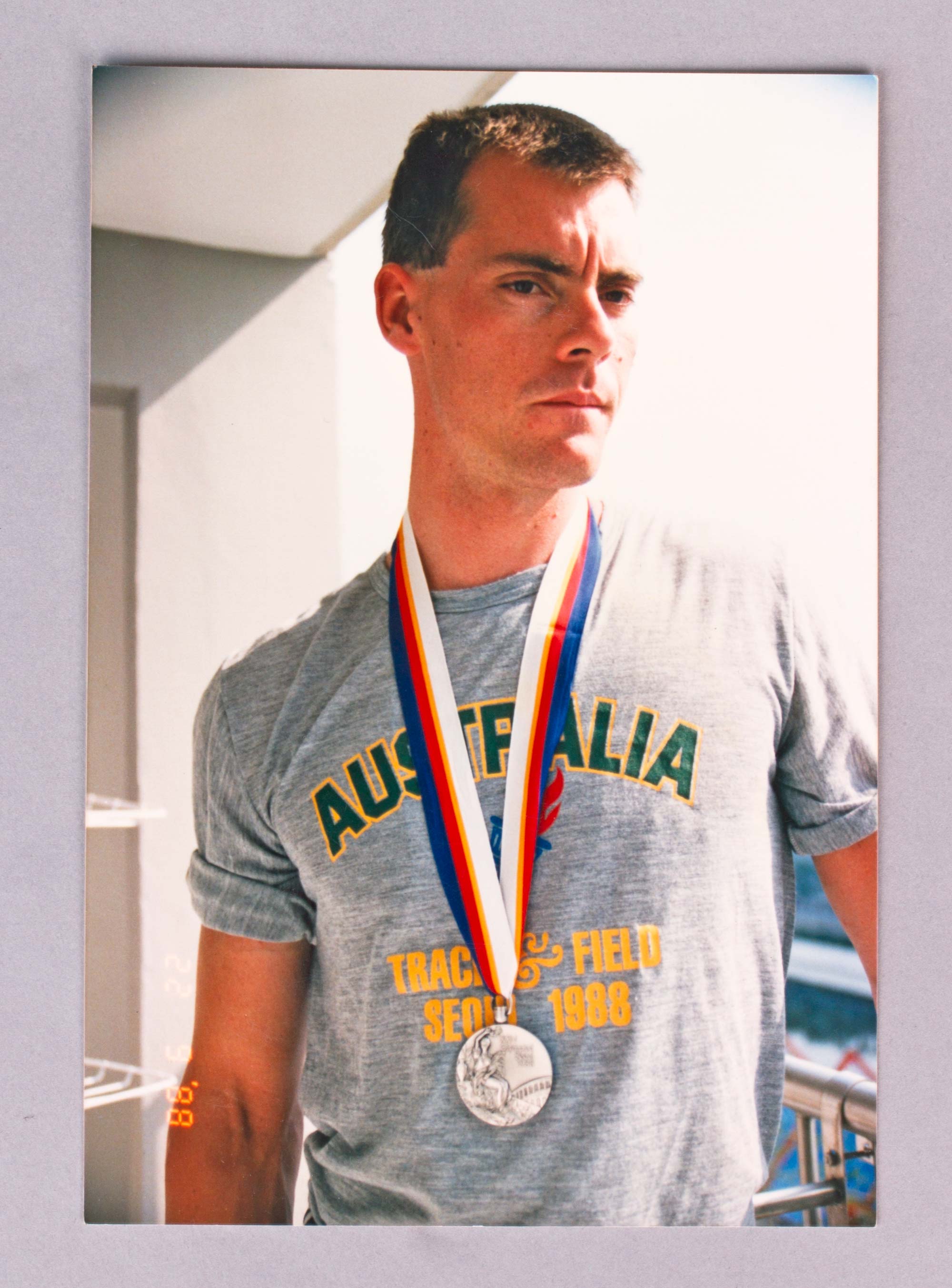

Martin Vinnicombe with his Olympic silver medal in 1988.

Shortly after it was announced that the 2008 Olympics would be in Beijing, Vinnicombe was briefly employed by the Chinese cycling federation to help coach women track sprinters but his time there didn’t last long.

“It was frustrating because of many reasons but one thing I found particularly annoying was them clearly talking about me, but not to me,” he said of the experience.

“That was when I decided to learn Mandarin; but I didn’t tell the federation.”

Within a few months he worked out the basics of the language and understood it well enough to be able to understand what was being said about him. And that heralded the end of his formal coaching career.

He married a Chinese lady, Li, and returned to Australia to settle in Tasmania. The couple have two children, Sebastian Hercules (born in 2006) and Sophia (born in 2009), and they now divide their time between Tassie and China where he does some consulting work for an export company.

Clamont claims that these bikes were made for two prominent Australian riders at the time: Martin Vinnicombe used one and the other is said to have been for Neil Stephens. Both have the smaller front wheels which is what was common at the time to try and help riders beat the wind.

He’s also been designing electric bikes and this project is the latest in an eclectic choice of work that keeps him occupied and satisfied.

Asked if he ever finds the time to ride when he’s down on the farm, he laughs and tells it like it is. “No. It’s too hard. It’s too hilly.”

An inventor… ahead of his time

After his positive test in 1991, Martin Vinnicombe returned to Australia and slowly started to get his life back in order. There was a brief stint as a coach of Malaysian track cyclists, before he started to move away from the sport and take up new hobbies.

One of the first ventures was making swords, “elaborate knives… that sort of thing” but he quickly diversified his interests.

On the stamp of the Cinelli ‘cow horn’ handlebars, you can read 66-40: the first number relates to the shape of the bars and the second is the width (centre to centre). You can tell that these are specifically designed to be used this way, and are not road bars that have been sawn off and turned upside down, because the Cinelli logos are still the right way up. The Cinelli 1A stem was first seen in 1963 but was still the choice of stronger riders as late as 1986. There were two different models in-between but the 1A was made all the way through to the 1990s. If the logo is in an oval and says, ‘Cinelli Milano’ it’s pre-1978 but the design didn’t alter much from 1963 onwards.

When Vinnicombe first heard of the SRM power meters that were coming out of Germany, he read up on the science behind the devices and created a power measuring device of his own, complete with right/left crank differentiation – and it was smaller than the SRM units.

He never completed school, for racing his bike is what took up his time, and he’s had no formal education since. So how did he devise the circuitry for the power meter? “If you want to make something, you have to think about it,” he once told me.

“That’s how it is with me. I thought about it… and did it.”

There were two bikes used for these photos: one had Shimano Dura-Ace track cranks (pictured), the other used SunTour Superbe Pro.

Establishing a life away from cycling

Vinnicombe has an analytical mind and boundless energy. When he bought his 17-acre property near Mount Roland in Tasmania, he noted the presence of oak trees. That inspired him to try his luck; he signed the papers, moved in “got a dog and went to see what they could sniff out”. And lo, he found truffles.

“That was okay for a while but it was too random, you may get them or you may not,” he says. “But it was fun for a while.”

There was a time when he’d turn up to watch a World Cup if he was in the same town, but he admits that his cycling days are long gone – even though he still tunes in to watch when it’s on and the recent world championships offered a good chance to reflect on how things have changed since turning up at the St George cycling club saying he wanted to race.

“Unfortunately my mother was an alcoholic,” he said about his childhood.

“I remember getting home from school when I was around 10 and she’d already be drunk. That went on for years and years, every day and every night.

“It was terrible but that isn’t the reason that I’ve never touched alcohol. There were lots of guys around me who hit the booze, and they still do it now and that’s cool if they want to – I don’t have a problem with it at all. I just don’t think it’s for me.”

His dry stance made one of his many career tangents a little difficult a few years ago; after growing bored with the truffle idea, he decided to make some wine.

“It was a good way to get in with the neighbours,” he says, “because, although I learned how to make the stuff, it was impossible for me to know if it was any good. I didn’t want to drink it, nor could I be sure if it tasted any good… so people in the area did the testing.” These days he’s happy with his lot in life. There have been a few commissions for him to make street furniture for a town near his farm – “just park benches and street lights… that sort of thing” – and he’s happy flitting between Tassie and China, spending time with his kids, “learning how to do oil painting and getting on with it but doing new things all the time”.

These days he’s happy with his lot in life. There have been a few commissions for him to make street furniture for a town near his farm – “just park benches and street lights… that sort of thing” – and he’s happy flitting between Tassie and China, spending time with his kids, “learning how to do oil painting and getting on with it but doing new things all the time”.

When track cycling was thriving…

For a few years at the end of the 1980s, however, there was nothing else in his life besides cycling.

He was from the last generation of track riders who raced without the advantages of aerobars but that’s not to say that other methods of beating the wind weren’t considered.

“When you look at what’s going on now and you consider what we used to ride, it’s really quite ridiculous that we thought we could go fast,” he says of the two Clamont track bikes he once competed on.

“We had our arms and shoulders poking out all over the place and, back then, we were riding with power alone. Yes, we had very tight skinsuits and there was some engineering involved but it’s nothing like what it is today.

“So much thought and science has gone into the products we see on the track now that it’s not surprising at all that we see world records fall as often as we do.

“Cycling is still very much evolving and better products help riders post faster times.

“The frontal area of a rider that pushes the wind has been reduced significantly and there are other big advantages like the rigidity of the frame, handlebars and stem.

“When I practised my starts, I’d have handlebars made by 3TTT set up so that they were pointing down but by the end of the session the position was nothing like how it started. It didn’t matter how much force you put on the clamp, they moved around during the course of a few hours.

“There was nothing that was good enough for big, powerful riders and still provide any kind of weight saving. Having all the new materials has done a fantastic service to the riders.” The fastest ‘kilo’ he rode on the Clamont bike was a 1:02.8 on Launceston’s Silverdome velodrome. (The photo at the top of this post shows him at the start of a race, held by a stalwart of Australian cycling, John Trevorrow.)

The fastest ‘kilo’ he rode on the Clamont bike was a 1:02.8 on Launceston’s Silverdome velodrome. (The photo at the top of this post shows him at the start of a race, held by a stalwart of Australian cycling, John Trevorrow.)

At the time, with the technology he had on offer, it was an impressive achievement.

“A skinny little frame like that wasted a lot of the power,” he says, sniggering at the thought of what equipment he had to work with.

His typical gear for a kilo was 45×13, “nowhere near as big as what they use now,” he recognises, but a lot of that has to do with what the bike could cope with.

For all the thought that went in to making the Clamont frames as stiff as possible, he admits it was far from ideal.

“It was like riding a rubber band sometimes. Frames could be sloppy and they’d move around a lot.

“People would tell me how to ride a kilo and remind me to keep down low on the track. If you have a bike that’s stiff enough, you can point it to where you want it to go. But until you get a bike that’s good enough to actually do that, you’re at the mercy of the machine.”

According to Vinnicombe, for all the flex of Geoff Scott’s Clamont frame, this was a good bike – especially when compared with what he used when he won the world title in Vienna. Handling issues were part of his concern but wasted energy from frame flex was a big problem. “We’re not talking about someone who is putting out 500 watts. These bikes had to cope with efforts of up to 2,000 watts or more! Of course the frame is going to move around,” he explains of the power output required for a kilo time trial.

“We’re not talking about someone who is putting out 500 watts. These bikes had to cope with efforts of up to 2,000 watts or more! Of course the frame is going to move around,” he explains of the power output required for a kilo time trial.

“The wall thickness of those Columbus tubes was down around 0.6mm. It’s created to hold together and propel a rider forward when he’s putting out around 2,000 watts – but it was crazy.

“There were alternatives back when I was riding but it involved riding a bike that would have weighed close to 15kg. There are compromises that you have to make.”

Racing on something that moved around as much as frames of the time meant that riders adapted their tactics to suit.

“We couldn’t get the power to stay in the bike because it moved around so much.

The crossover stays — as these were generically called — were used in Australia during the 1930s by Barb, a premium bike brand made by the Findlay brothers in Melbourne. The design has been around for a long time but Vinnicombe believes that this particular bike was modelled on a Cinelli frame from the 1980s.

“I had to concentrate on getting out as hard as but not so fast that the frame flopped around too much. Once the bike settled down, that’s when the power was applied. So much energy was lost at the start because of frame flex and there was no point trying go fast then – the emphasis had to be on remaining smooth and being efficient. Once it was time to sit, that’s when the gains could really be made.”

‘Kilo’ and ‘hour record’ bikes… one and the same

When Clarence Street Cyclery loaned us these bikes, the claim was that one was Vinnicombe’s and the other had been ridden by Neil Stephens who had set the outdoor hour record on it in the 1980s.

Remember, this was a time when there was a strong distinction between professional and amateur cycling, their indoor and outdoor records, elite track races – including the Olympic Games – were contested on concrete velodromes, and there weren’t the restrictions with design that exist now.

Some photos were sent to Stephens for him to comment on and he replied with a brief note: “Bloody hell! Where are those bikes? Geoff Scott built them but it was my idea and design.” Vinnicombe isn’t convinced that Stephens’ recollection is all it should be on this topic.

Vinnicombe isn’t convinced that Stephens’ recollection is all it should be on this topic.

“The design was originally done by Cinelli in Italy. Bikes of a very similar aesthetic were created for Hans-Henrik Ørsted who won the professional 5,000m individual pursuit three times (1984, 1985 and 1987).

“This design was borrowed from Cinelli and built by Geoff Scott, the man behind the Clamont brand. It was financed by Tony Cook who owns Clarence Street Cyclery, but it was Geoff who did the welding and the painting. He was a real craftsman.

“Stevo might have seen it in a book and thought he came up with the idea, but he didn’t. Cinelli first released a bike with this frame design in 1984. The Clamont bikes are from the 1986 and 1987 seasons.”

But Vinnicombe wouldn’t ride one of these when he won the world championship in Vienna.

“The bike I rode to win the kilo in 1987 was absolute crap. It was some rubbish that Brian Hayes and Charlie Walsh put together and the geometry was totally terrible. But that’s what I had, and if I dared to complain or comment about it then I’m not sure I’d have had the chance to race.

“The bike I rode in Vienna was shit and it took weeks for me to settle into it and start to feel even remotely comfortable on it. I had to make so many adjustments to make it right but it all worked out well. I got the gold medal,” recalls Vinnicombe.

“For some reason, Hayes decided that he wanted to change the geometry and the shape of our bikes and it just didn’t work! The angles were all wrong… the seat had to be too far forward to be useful and it stuffed up my balance completely.

“Track racing is a very precise sport; you set your bike up and you want to know that you turn into a bend and the thing is going to turn when you want it.

“The bike that I used for the world championships seemed to drift off in any direction… I hated that bike! I rode it for the championship and, in 1988, I went back to my old bike. It was because of that experience that I asked Geoff Scott to make more frames for me.”

Without today’s design limitations like the ones imposed by the UCI, frame builders had more freedom and although the advent of aerobars was yet to happen there were features that helped the rider get lower.

A smaller front wheel was common at the time and these were no different: 700c at the back and 26-inch at the front.

What was it like to ride? “It wasn’t really that good for handling,” says Vinnicombe.

“Wheels of the same diameter are naturally better to ride if you want control. But we were looking for advantages against the wind. Riding a small front wheel makes the bike feel twitchy. It also meant that we had to use different tyres from the front to the back.

“We were sponsored by Continental but I had to have a Vittoria on the front because the other option was too wavy in the bends. With the set-up that I did use, it hung on nicely.”

The biggest improvement from this design was that it made the frame triangles smaller and, so the theory went, made the frame a little more rigid.

“Small riders had a great advantage because guys like Jens Glücklich and Aleksandre Kiritchenko could use smaller bikes and they had much stiffer frames. They were little muscly guys but big bastards like me had to use larger frames and the bike wouldn’t settle in. This is deceptive because the triangles were made to be as small as. You can see where the top tube bends up and the back seatstay goes across the seat tube and onto the top tube – that effectively makes it into a smaller frame. It’s a clever design.”

– Interview by Rob Arnold