Glasgow hosted the UCI’s first ‘super world championships’ and crammed the crowning of 200 champions – in multiple disciplines and numerous events involving 6,000 competitors – into 11 days. It was bold, but it was bewildering…

Comment by Kenny Pryde

It’s hard to tell, sometimes, if a Glaswegian is drunk or just being friendly. Hell, I’m a Glaswegian and sometimes I struggle. So, when one local rejoiced in the efforts of Scottish Cycling to get ‘weans on bikes’ it wasn’t obvious if he was serious or sarcastic. “They’ve got kids on bikes and when they pedal, they’re mixing up a milkshake that that they get to drink after they’re done.

“Anything that tries to get weans on bikes and taking exercise has to be good; they’re all just on their phones, sat there, wanting entertainment at the end of their arms.”

When ageing and dissolute denizens of Glasgow realise that ‘kids’ need to be taking more exercise, you know the problem of obesity and sedentary lifestyles has escaped from think-tank papers and government departments into the wild. All of which presumably made Glasgow hosting the first ever cycling ‘Super Worlds’ a little bit easier to sell to the natives.

In the end, we’re talking about the ‘L’ word here – yes, we’re talking legacy. Getting more people on bikes, riding bikes – any kind of bikes, even if it’s for a strawberry milk shake – was the name of the game at Glasgow 2023. Laudable as that effort always is, the preoccupation of almost everyone in Glasgow with an eye on the championships was the state of the roads.

The level of disrepair in Scottish roads is a major political issue and news about stretches of roads in Glasgow and Central Scotland made headlines.

Forget kids on bikes, the locals are ragin’ – which is to say angry – about potholes or rather the fact that the potholes have been filled in for a bike race, while the roads on their streets look like they’ve been carpet bombed.

It was a predictable but hopelessly parochial attitude.

Craig Burn was Director of Strategy, Policy and Impacts at the Glasgow championships and his concerns extended far beyond surface treatments and potholes. Burn, appointed in January 2021, was positively evangelical about the potential for these ‘super championships’ to galvanise Scotland’s attitude to cycling. Hitherto it’s fair to say that there were lots of ministries – tourism, transport, health, business – that weren’t talking to each other enough when it came to cycling. Burn hopes the Glasgow championships will change this.

“There’s £8 million that’s been allocated to part fund projects like new pump tracks and specific cycling circuits, like the new one kilometre one at West Lothian,” Burn said. “That was given £600,000 from the fund. It’s a facility that can put on circuit races, or help newcomers develop basic riding skills to get their confidence up.”

Increasingly, host cities are paying a lot more attention to what they are getting for their money. In Glasgow, the initial budget inevitably rose following the global energy crisis and inflation hike, so the final tally is likely to be a few numbers north of £70 million. “When you compare that number to the price of a multi-sport Games like Birmingham Commonwealth Games, there’s no real comparison though,” insists Burn. “This is cheap in comparison.”

The Birmingham budget was £778 million, over 10 times what Glasgow spent, and you have to wonder what the international impact of those Games were, compared to pukka world championships. Does anyone in the USA or Europe care who won the Commonwealth Games road races? Even if you live in a Commonwealth country you can’t even remember, can you?

When it comes to measuring the championships’ economic impact Burn is sanguine.

“There’s no way to accurately measure hotel bed occupancy and correlate it with the championships. If we had had the money to develop and app that people could use to check in and out of events we could have used that data to calculate that sort of thing more accurately, but we couldn’t afford an app. The budget wasn’t there,” adding that independent audits and surveys will be carried out to quantify the economic impact.

Anecdotally, the ‘Spitfire Espresso’ on Ingram Street, insisted that the business had done spectacularly well during the world championships. When pressed to quantify what “really busy” actually meant, the reply was “We’ve done twice as much business and on two days we pretty much sold out of everything,” explained a staffer with a smile. It was also every Australian team’s go-to for a coffee throughout the championships.

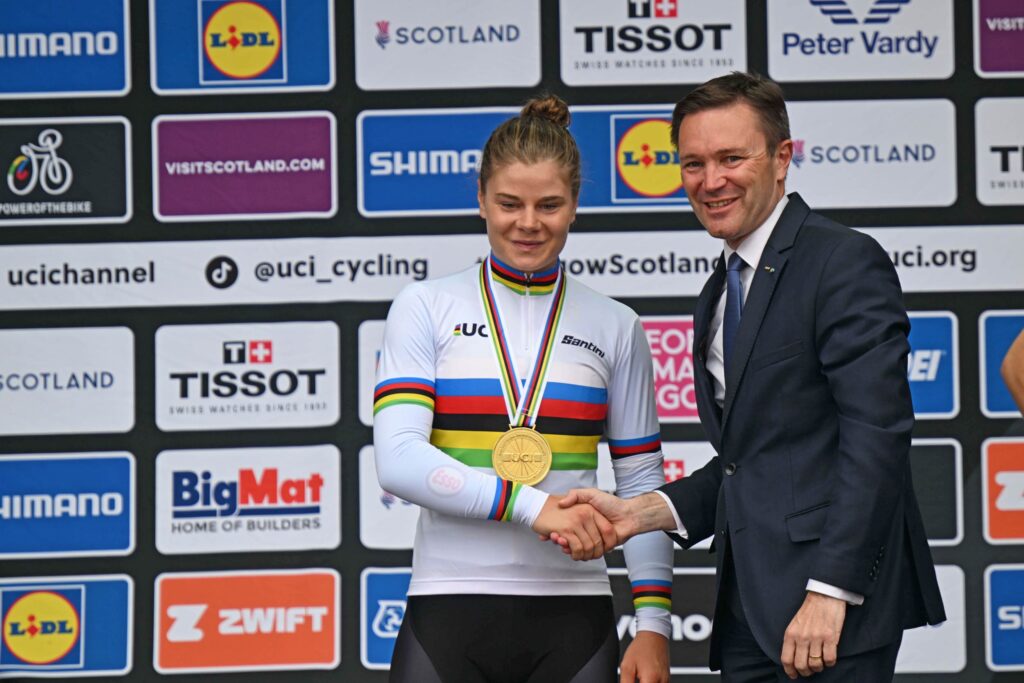

Lotte Kopecky, a triple world champion from #Glasgow2023, looks thrilled to be sharing the podium with UCI president David Lappartient.

From a media perspective, the super worlds were impossible to cover or even follow.

David Lappartient’s hope that a ‘multiplier’ effect would result in greater media coverage for fringe cycle sport proved forlorn. Thomas Turner, media lead at British Cycling, reckoned that these weren’t so much cycling world championships, but rather needed to be seen, from a media perspective, as “a multi-sport event, like the Commonwealth Games or Olympics. If a media platform wanted to cover these championships properly, they needed to treat it like an Olympics”.

Turner was absolutely right that a ‘normal’ journalistic staff and budget allocation would simply not be enough to cope with the 600 medals and thousands of competitors.

Scotland is a small place, but competitions were spread from the Borders (XC mountain biking) to Glasgow (road races, BMX events and the velodrome), Stirling (time trials) to Fort William in the Highlands for downhill mountain biking. And that’s ignoring the para-cycling racing in Dumfries, the world Sunday club run championships (aka. Grand Fondo championships) in Perth.

There were cycle-ball and artistic cycling championships too but, honestly, who knows where they were being held, there’s only so much useful info a human brain can deal with.

While Scotland could fit into any Aussie state with room to spare – even Tasmania – it’s still big enough to need more than a couple of journalists to cover it, especially when the events are spread as far and wide as they were.

Which media company was going to spend an Olympic-sized budget on covering cycling’s super world championships though? It’s still “just cycling”, not the Olympic Games.

Lappartient’s was a nice idea, but the UCI president completely disregarded the reality of modern media and shrinking newsroom budgets.

National Federations were struggling with human resource too. Smaller nations shared mechanics, soigneurs, drivers and ancillary staff across lots of disciplines, but with the super champs overlapping and spread over hundreds of miles, they had no chance of doing them or their riders justice. That assumed they brought a full complement of riders for all disciplines in the first place.

On the plus side, fears about widespread indifference among locals proved to be groundless, as the Scottish public actually did take the championships to heart.

There were masses of volunteers in and around venues and routes as well as spectators from all over the UK, not just Scotland, who turned up to cheer competitors and blag bidons. True, some of the velodrome sessions had empty seats (at £30-£70 a ticket per session, they certainly weren’t giving away entry to the Sir Chris Hoy velodrome), but the main finals were raucously supported and the GB riders gave them plenty to shout about.

Overall then? As a spectacle and a logistics exercise, the UCI’s all-in-one super champonships in Glasgow worked. From a Scottish perspective, the crowds (eg. an estimated 190,000 people on the roads of Glasgow for the men’s elite road race) and the racing as well as the television coverage from the BBC was exemplary.

As a concept intended to stimulate wider cycling participation, it’s too early to say.

From a UCI point of view there’s plenty for Lappartient and his cohort to think about. And make no mistake these super championships were his: he was very clear that this idea first came to him (he didn’t say “in a vision”, to be fair) when he was only president of European cycling in 2017. The ‘Super Worlds’ was, in fact, part of his successful UCI presidential bid in 2018, so they are his ‘baby’ and it had teething problems.

The Chris Hoy velodrome centre was packed and stressy with able bodied and para-cycling competitions running back-to-back, the medal ceremonies were held off site and the plans to include the junior world track championships at the next super championships seem wildly optimistic – or utterly foolhardy.

The Glasgow organising committee’s decision to close the championships with the women’s race was intended as a statement to promote women’s cycling, yet arguably cost some spectators. There’s a hardcore of road race fans who travel to the world championships uniquely for the road races. So, the theory has been, they can turn up on Thursday and leave on Sunday night having seen junior men, women, under-23 as well as the elite men’s and women’s races.

Spreading the road racing over a whole week meant some turned up for the men’s elite and drove their camper vans home.

It’s vital to be open to change and challenge orthodoxy, but there are times when you have to accept that there’s a reason why things have been organised as they have been.

The local organisers, volunteers and logistics teams deserve a lot of credit for being able to stage Lappartient’s bold vision, but it looks like overreach. From a Scottish perspective, the circus has already left town and what ‘north Britain’ needs now is a Scottish government minister to make sure that the agencies and national government departments involved – tourism, active transport, sport, Scottish Cycling, Business, Health, ScotRail – will get together and come up with a policy that truly will exploit the legacy of Lappartient’s grandiose cycling festival. Otherwise, all Glasgow will have as legacy is photos, a Highland cow mascot and a bidon nicked from a bike.

– By Kenny Pryde