Ugo De Rosa was a craftsman who created beautiful bikes. He passed away this week, aged 89. In memory of the man who built a brand that began in 1953, we look back at a ‘Retro Review’ about Evgeni Berzin’s Giro-winning Titanio from 1994.

– Words by Warren Meade. Photos by Yuzuru Sunada.

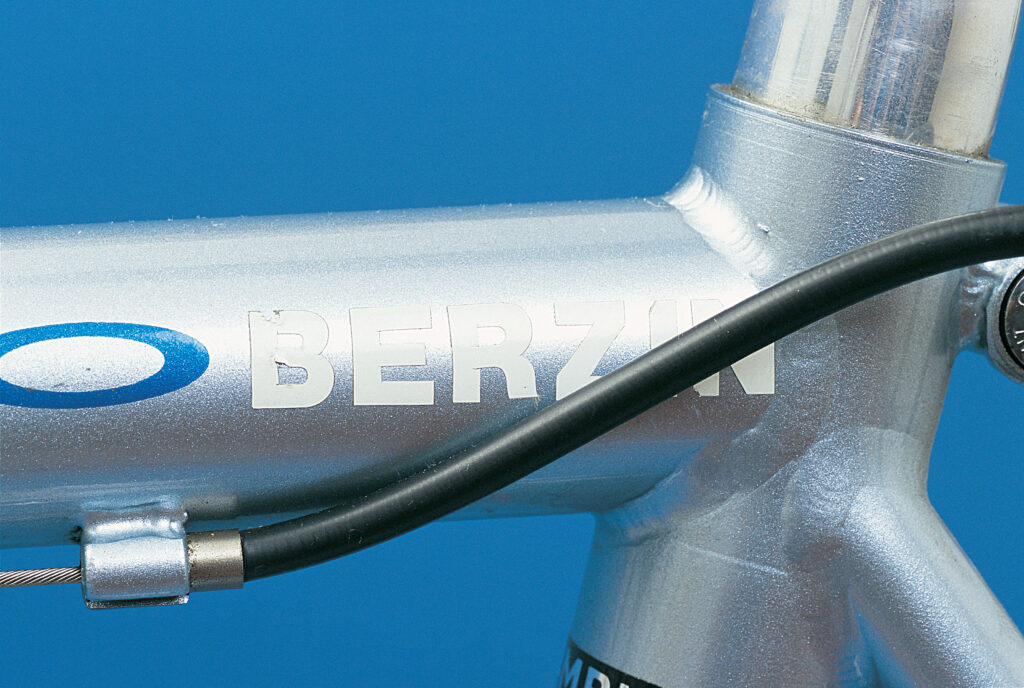

The famous De Rosa heart symbol is proudly displayed on Evgeni Berzin’s Titanio head tube. Also featuring on this bike from 1994 are the revolutionary dual pivot brake callipers, ergonomic bend handlebars and cork tape. The Campagnolo Ergopower levers you see here were introduced for the 1992 season.

– This article was originally published in RIDE Cycling Review #32 (September 2006)

This bike was ridden to victory in the Giro d’Italia of 1994. Evgeni Berzin’s multiple victories that season were achieved on De Rosa frames but his dominance in racing can be credited to other products…

Ah, De Rosa. The very mention of the name is enough to make the serious bicycle enthusiast swoon and the credit card run for cover. You want to be taken seriously by the elder statesmen in your local peloton? Turn up on a De Rosa.

Like many of his contemporaries in post war Italy, Ugo De Rosa started out as a young man simply working in his uncle’s bike shop. But before too long he had established his own business, concentrating on building frames and bikes for racing cyclists.

Ugo De Rosa went on to create and supply equipment for such superstars of European cycling as Raphaël Geminiani, Eddy Merckx, Francesco Moser, Roger De Vlaeminck and Moreno Argentin. That most of these riders approached him to build their bikes, rather than the other way around, is sufficient tribute to his skills as a mechanic par excellence.

De Rosa is widely credited with helping Eddy Merckx set up his own manufacturing facility in 1981. Early incarnations of Merckx frames bear a remarkable similarity to the De Rosa offerings of the same period. No frills, ‘just right’ proportions, sensible angles and not too short in the wheelbase.

Want to go fast down hills and around corners without fearing for your life? Step back in time and get onto one of these classics.

In 1990, De Rosa started researching the possibilities of manufacturing a line of titanium frames. Bikes made from this exotic metal were by no means a new idea at the time; the first titanium frames had been produced in the 1960s by Speedwell of England. Teledyne Titan frames saw small scale production in America in the 1970s, and titanium offerings from market leaders Litespeed were readily available in 1994.

This well-crafted titanium stem by 3T features the once-traditional internal expander bolt retention system. The quill design and threaded headset were about to be replaced by the lighter and simpler Aheadset concept that is universally used on bikes in the market today.

By the 1990s, De Rosa had an enviable reputation in the crafting of traditional steel bicycle frames. One can surmise that the company’s reason for pursuing perfection with a new material was motivated by the desire to stay at the very top of its chosen field.

The weight of a bike was becoming an important marketing issue, taking over from the emphasis on aerodynamics in the 1980s.

With the advent of gear shifters incorporated in the brake levers, clipless pedals, eight-speed drivetrains, deep section alloy rims and clincher tyres, the weight of a top level race bike had actually increased in the previous five years.

The De Rosa Titanio featured on these pages was ridden to victory by Evgeni Berzin in the 1994 edition of the Giro d’Italia. The 23-year-old Berzin had burst onto the scene earlier in the year by winning Liège-Bastogne-Liège, and was a member of the spectacularly successful Gewiss-Ballan team which won over 40 races during that season alone.

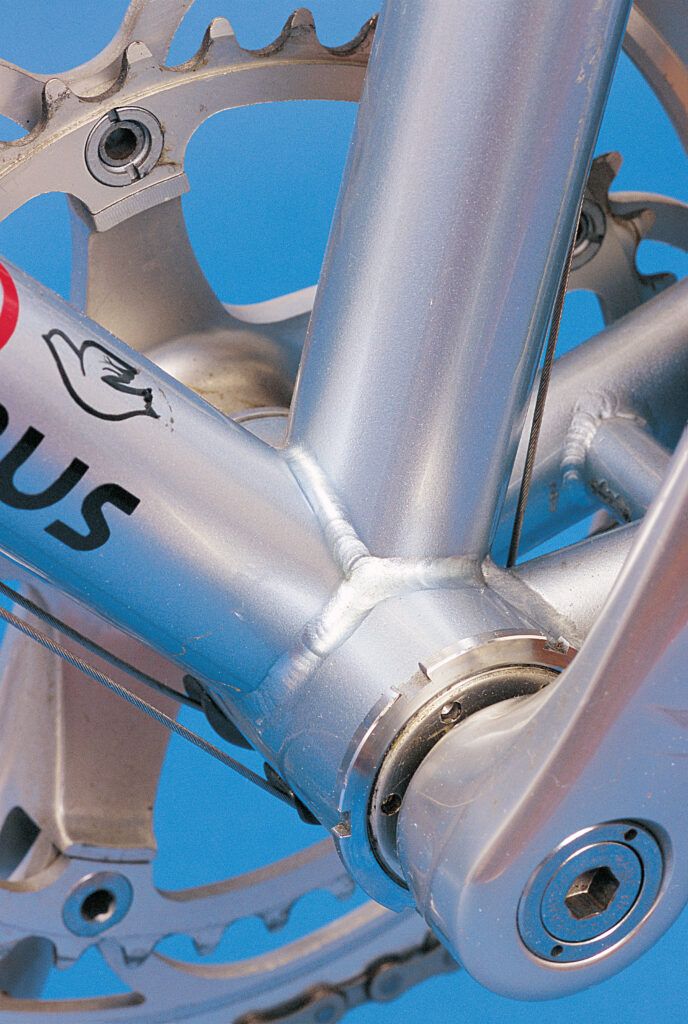

The junctions on the Titanio frame could qualify as industrial art. The welders of titanium are highly skilled and what you see is what you get. These joins cannot be doctored to hide any flaws. The ubiquitous Campagnolo seat binder bolt links this bike to millions of other classic cousins, this simple little part’s reign stretching back over 30 years.

Looking at the bikes of the peloton in 1994, there was a lot more variety in frame materials and construction methods than had been seen in the past, and a completely different scene to what one encounters today.

Some manufacturers had pioneered the use of aluminium and were well represented (Alan, Vitus, Cannondale, Klein et al).

Others had ventured into carbon-fibre (Alan and Vitus again, Kestrel, Look, Time, Trek, Giant, Coppi… etc).

Some were showcasing titanium (including De Rosa, Litespeed and Merlin).

And plenty were persevering with steel. Colnago, Pinarello, Eddy Merckx and many of the above were keeping an iron in all fires.

It’s fair to think that, all these years later, we could expect the argument over the ultimate frame material to be settled. But while carbon-fibre seems to have won the battle for supremacy, it may only be on top for a short time. Most mainstream manufacturers are continuing to develop aluminium frames, others are fine-tuning their titanium offerings, and some are spending time and money perfecting that born again wonder material, steel.

Titanium is still held in high regard for all the right reasons but has been stifled in the marketplace for the last three decades due to its price. Now that many of the better quality carbon-framed bikes cost well over $7,000, I can’t help wondering whether a titanium version of the same machine would cause any more wallet trauma.

In 1994 a titanium frame was more than double the price of a top-of-the-line steel version, while now a titanium frame is about the same price as a genuine team-issue carbon one.

The use of titanium extended to the rails of the Selle Italia Flite saddle.

This version of the Campagnolo Record seatpost sends shivers down the spine as there are numerous horror stories of injuries inflicted on hapless riders if (or when) it snapped at the slightly too finely-crafted section near the top.

We’ll get back to Evgeni Berzin’s machine in a minute, but while we’re on the subject of titanium it does have some important attributes. It doesn’t rust, it won’t work harden (get brittle), it rarely breaks if you crash, it looks fantastic either raw or polished, it doesn’t falter in extreme heat or sunlight, it doesn’t fail without warning and, last but not least, it’s very light. No other frame material has all of these virtues.

Now, back to Mr Berzin’s bike. Riding for a team that won 40 races in a year, and personally winning a major Classic and a Grand Tour, you’d think that the press reports from the day would be full of details about these revolutionary titanium bikes. I found no shortage of material about the exploits of Berzin and his Gewiss-Ballan team, but there was a notable shortage of mentions of the bikes these ‘supermen’ rode.

Was not a victory in the Giro d’Italia by an almost unknown 23-year-old worthy of a headline like: ‘Neo pro wins Giro on a revolutionary titanium bike’? No. Unfortunately the team’s exploits were credited to another kind of modern technology, and the wonder metal was hardly mentioned in despatches at all.

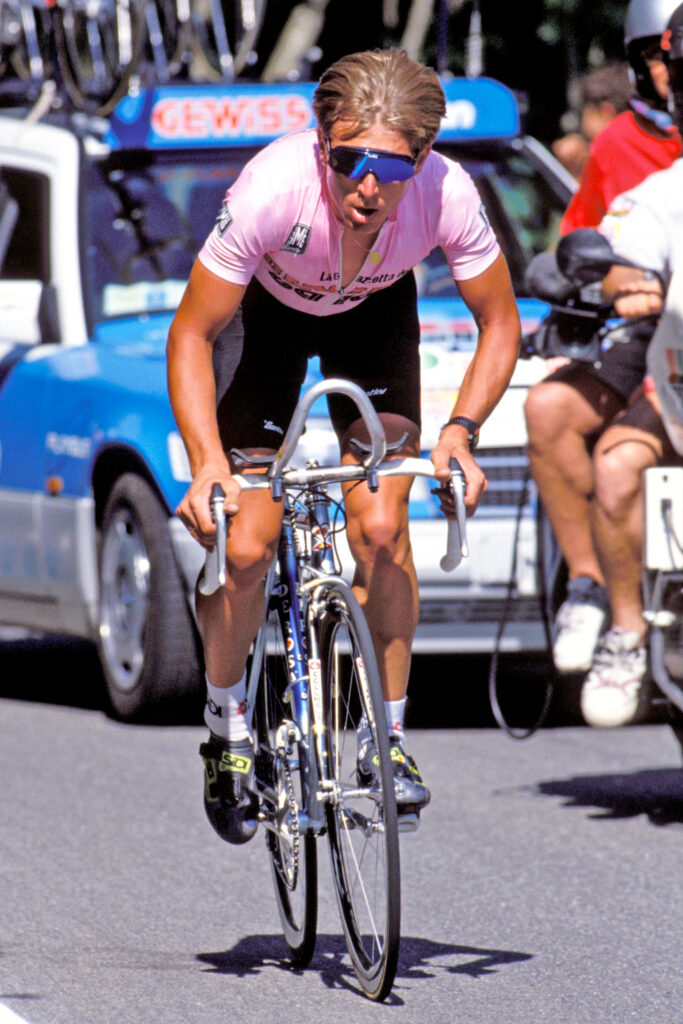

Riders from the Gewiss-Ballan team were dominant throughout the 1994 season… [it was a] team that employed the services of Dr Michele Ferrari. In the Giro d’Italia, Berzin finished second in the first time trial, before winning the fourth stage and claiming the maglia rosa. He won the next time trial by over a minute and used the Titanio (with clip-on aerobars, pictured) to beat Miguel Indurain in the 35km TT on the Passo del Bocco mountain.

Evgeni Berzin’s De Rosa Titanio was about as nice a bike as you could spend your hard earned dollars on in 1994. The eight-speed Campagnolo Record Ergopower groupset was introduced in 1992, with an upgrade to carbon housing released in 1994 (while composite levers came later in 1999).

These levers used an improved rubber hood compound, and featured the clever and simple quick-release pin that was positioned near the top of the handle. This still makes more sense than the cam type quick-release down on the calliper that other brands have persevered with, and the pin is an important feature of the Campagnolo system.

It’s interesting that the company moved away from the cam style quick-release, as they had introduced it with their Record brakes way back in 1967. They weren’t the first to appear with the pin in the lever idea though, this being used by both GB and Weinmann back in the 1960s.

Carrying on from the C Record group of 1986, the crankset retains the ‘hidden’ fifth spider arm which is incorporated in the crank itself. This feature saved weight, increased rigidity and made for arguably the most aesthetically pleasing crankset of the modern era.

The pedals were branded Campagnolo but had a system that was a replica of Look’s. By 1994 the last of the ‘toeclips and straps’ brigade had disappeared from the peloton. The last exponent of the old system, the legendary Sean Kelly, retired at the end of 1994. He continued, however, to use the 100-year-old foot retention system throughout his career and only tried clipless pedals in his final year as a pro.

The De Rosa’s titanium frame is complemented by the titanium stem made by 3T. It was a quill style design which fit snugly inside the steering tube rather than clamping around it as we see today. Although this 3T version would have been the ultimate incarnation of the old expander bolt system, it was still heavy and complex compared to the Aheadset system used on virtually all high-end bikes today.

The De Rosa is equipped with Campagnolo Shamal wheels which deserve a special mention. They caused a stir when first introduced and gave all those with an obsession for exotic equipment a serious bout of the ‘wants’. They were so different to the traditional designs that wheelbuilders thought they were seeing the beginning of the end for their craft.

Lacing spokes to hubs and rims had been the black art of skilled mechanics for over 100 years. Abilities in this aspect of the trade separated the celebrity bike mechanics from the bike washers and puncture menders. Get a reputation for building good, reliable wheels for serious riders and you could set yourself up with a lifetime of interesting, well paid work.

Shamals were expensive, seemed to have hardly any spokes and came from the factory as a complete unit. They were built by a faceless factory hand with no reputation for wheel wizardry. Would they be up to the task? Well, their durability proved to be just fine but the price, weight and the harsh ride qualities meant that these deep section alloy rims and their relatives never really took over the wheel world.

Look around the bunch today and you will still see all sorts of choices being made for wheels and tyres, with clinchers and tubulars, aero and traditional rim sections, carbon and aluminium, and anywhere between 12 and 36 spokes per wheel. But except for flat time trials and triathlons, deep section aluminium rims seem to have all but disappeared.

Even though they were made until 2001, Shamal wheels have been relegated to collector’s item status, their main use being on exotic ‘caffeine culture’ bikes where the combination of an Italian steel frame (with a dash of chrome), Shamal wheels, eight-speed Campagnolo Record and maybe even some Record Delta brakes will instantly identify you as a bicycle connoisseur or ‘true believer’.

While some aspects of the 1994 season have faded from memory or been proven less than notable, others have retained their importance and are fondly remembered.

In 1994, a 20-year-old first year pro named George Hincapie was one of a mere handful of courageous finishers in a Paris-Roubaix classic held in atrocious conditions. George’s friend and slightly older mentor Lance Armstrong, the 22-year-old reigning world champion, finished second to the victorious 23-year-old Berzin at Liège-Bastogne-Liège.

Berzin rode his titanium De Rosa, Armstrong rode his steel Eddy Merckx with its De Rosa heritage. The tradition and the big names weaving a web that stretched decades back in time and forward to the present. And had you asked a sample of 100 people in 1994, who out of Armstrong and Berzin was more likely to be a future Tour de France winner, 100 of them would have said Berzin.

While Berzin’s star may have faded over the last 12 years, if you’d had the good fortune or good judgment to purchase a De Rosa Titanio in 1994 you would still have a perfectly serviceable and reliable racing bike worth as much, if not more, than what you’d paid for it. Swap those Shamal wheels for a set of the industry’s latest lightweight offerings and the bike would be race ready. A timeless De Rosa with the oh-so sweet aura, hewn of titanium, a best friend that cannot grow old.

– By Warren Meade