A recent column by Mikkel Condé on the Inner Ring site has prompted us to revisit a series about gambling in sport that Lisa Jacobs wrote for RIDE in 2012. In this flashback, Jacobs outlines recently introduced regulations that relating to the topic and questioned how cycling might be able to adapt considering the nature of racing and how tactics are played out.

This is part one of the series that was originally published in RIDE #56 (published in May 2012).

Betting: the new doping?

Will recently-introduced anti-corruption laws change the way bike races are ridden?

– By Lisa Jacobs

In the first of a series relating to the law and cycling, Lisa Jacobs considers what the effect of anti-corruption regulations created to limit the chance of match-fixing will have on sport. Gambling has the potential to have greater ramifications than the effect of doping…

For years, the spectre of doping has cast a shadow over pro cycling. Since the 1920s, when anti-doping measures were first introduced into the peloton, drugs have posed the biggest threat to the sport’s integrity. Now – if we believe the UCI – the sport is cleaner. Biological passports and rigorous drug testing have made it harder for professional cyclists to artificially enhance their performances with drugs. But there will always be cheats and if it’s not drugs it will be something else. RIDE looks at a new threat to cycling, one that is predicted to be the biggest challenge facing global sport over the next 20 years: corruption.

A global threat to sport

Corruption in sport is the subject of an intense and growing global focus. The criminal sentencing in the UK in November 2011 of three Pakistani cricketers and their manager for accepting bribes to bowl no-balls at the Lord’s test in August thrust the issue of corruption in professional sport into the spotlight. In the past 10 years, instances of corruption have been detected in almost every major professional sport including – but not limited to – cricket, football, horse racing, snooker, Formula 1 and sumo wrestling.

Former Australian senator Mark Arbib recently summarised the challenges facing elite sport when he resigned from his role as federal sports minister in March. Arbib stated that, while doping had been the ‘great shadow’ cast over sport in the 1980s and 1990s, it is match-fixing which now poses the greatest threat to sport’s integrity.

The role of betting in incentivising corruption

Why is match-fixing in sport so poisonous? Essentially, it is due to the growing popularity of gambling. Globally, the sports betting industry is worth hundreds of billions of dollars. As that value grows, so can the incentive for betting-related corruption. In Australia, betting on professional sports is growing, both in terms of the amount of money gambled, and the range of bets that can be placed. Australia has not yet had the high-profile scandals seen overseas, but the risk of betting-related corruption is growing.

Match-fixing, and the abuse of insider information, distorts betting outcomes and can involve significant fraud. In sports where betting is prevalent, like AFL or cricket, it has the potential to cause significant economic disruption. In all sports, regardless of money, match-fixing undermines the principle of fair play on which sport is based.

A matter of perspective

In most sports, we call match-fixing ‘cheating’. The idea of determining the outcome of a sporting event by anything other than athletic ability is abhorrent. So when a football referee fails to call offside on a match-winning goal, a cricket player is caught out early, or a basketballer misses an easy shot, and we find out that they were offered money to do it, we scream blue murder. It’s a scourge of almost all codes of modern sport… except for cycling.

In cycling, deals are made all the time. Some are blatant, some more clandestine but it is almost an accepted part of the racing culture. And they usually involve money, because pro cyclists race for glory but also financial reward. Riders in a breakaway agree that one will take the intermediate sprints and the other the stage win. Two friends agree that one will win this week in return for helping the other win next week. Alexandre Vinokourov famously (allegedly) offered 100,000 euros to Alexandr Kolobnev in the final kilometres of last year’s Liège-Bastogne-Liège to sit up so that ‘Vino’ could take the victory. A financial exchange mid-race is nothing new and it happens on many levels – from the oldest of the Monuments, to the Australian road race championships, to the local club race… all under different circumstances but all very real.

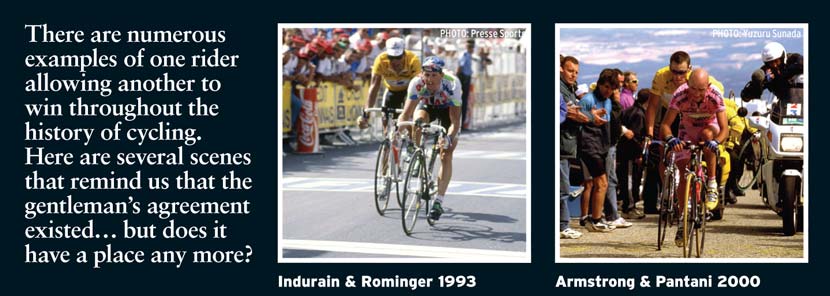

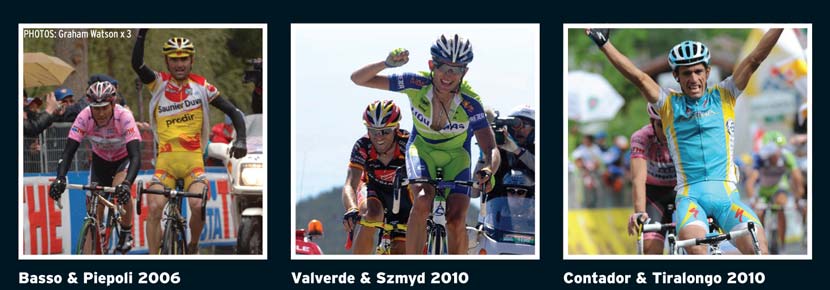

There are many other simple examples of deals – attempted or real – being done on the bike midway through a race. Collusion is banned by the UCI but it’s rife in all levels of the sport – sometimes it’s obvious to even the casual observer, other times the arrangement is done in such a way that it’s impossible for even the commissaires to realise it’s happening.

There are also instances of an agreement being carried out because of the ability of the riders involved. Often it’s considered a gentleman’s arrangement and rarely does it attract any scorn; in fact, praise is often heaped on someone for a display of ‘honourable’ work. Consider Paolo Tiralongo’s win in stage 19 of the 2011 Giro d’Italia ahead of that race’s ‘Patron’, Alberto Contador. The Spaniard could easily have beaten his Italian rival but it was a payback for an earlier favour and it was obvious.

Other incidents have been so blatant that riders can be seen braking to allow another to reach the line first. In the fifth stage of the Critérium du Dauphiné in 2009, Sylwester Szmyd teamed up with Alejandro Valverde early on the slopes of Mont Ventoux; together the pair built an advantage of almost two minutes on the pack that included the leader of general classification at the time, Cadel Evans. In an obvious display of a ‘gentleman’s agreement’ the Polish rider swapped off with the Spaniard all the way to the summit.

When the moment came for Szmyd to dart ahead for the agreed stage win, he lost his senses. “I can’t hide that having done all my career as a domestique,” he said. “I was in trouble when it came time to win. I was stressed out.”

Even so, Valverde had built up such a sufficient buffer from their collective toil that he was going to claim the yellow jersey. But Szmyd suffered cramp and lost contact with his former companion. On the final turn the new race leader feigned a problem with his gears, he stopped pedalling for significant stretches and, eventually, his rival worked his way into the lead. Valverde honoured his part in the obvious arrangement… but it looked absurd. The new leader of GC virtually had to stop so that he could allow his ally to reach the finish ahead of him.

This kind of fixing is not seen as wrong because it’s part of the strategy that earns cycling its reputation as a “game of chess on wheels”. It doesn’t involve an entire team or field. It may not work due to other variables in the race. And, largely, it affects few beyond those people directly involved.

The agreements are made between riders on the spot, not premeditated. The objective of the rider offering the fix is to get a better result, not to distort a betting outcome. For these reasons, it’s difficult to categorise this behaviour as corrupt. But it does affect the outcome of competition. So why do we not mind it in cycling, when we are willing at the same time to throw cricketers in jail?

To find out, let’s look back to the challenges that Mark Arbib identified: match-fixing and doping. It is clear which has posed the bigger problem for cycling. Historically, doping has been the method of choice by which cyclists distort competition outcomes. The economic rationalists of the peloton can see that it’s easier to make one rider go faster than anyone else than it is to fix agreements with every single cyclist in a large bunch. So the importance of an agreement between two riders on whether or not to sprint fades into insignificance when compared with the fundamental, inarguable wrong of doping.

But sport evolves, and people’s perceptions of what constitutes acceptable race tactics change over time. Doping, for example, hasn’t always been considered wrong.

Up until the 1920s, it was thought to be a normal part of racing. There are reports of cyclists dying from performance-related doping as early as 1886. But it was only as late as 1968 that drug testing had been introduced into the Tour de France – and even then it was largely because of the death of a rider in the previous edition… and still there were protests.

By the 1980s, the USA had banned blood doping. Behaviour that was once deemed normal came to be seen as detrimental to the integrity of the sport. Are the ‘gentlemen’s agreements’, which today are an acceptable part of racing, destined to go down the same path?

New laws and their impact on cycling

In June 2011, Australian state and territory governments signed up to a national policy on match-fixing in sport. The framework is designed to protect the integrity of sport, and targets inappropriate and fraudulent sports betting and match-fixing behaviour. The cornerstones of the framework are:

• Nationally consistent legislation criminalising match-fixing in sport

• Mandatory information-sharing agreements between sports governing bodies, betting operators and law enforcers, designed to detect and investigate suspicious betting conduct (similar to those which exist in Victoria under the Sports Betting Act)

• Nationally consistent codes of conduct for sports

• Support for the development of an international anti-corruption body similar to WADA

The NSW government has been the first to act on legislation, and is currently considering an amendment to the Crimes Act to impose criminal penalties on conduct that corrupts the betting outcome of an event. Under the proposed law, conduct would be illegal if: (a) it is undertaken to obtain a financial advantage as a result of betting, and (b) is contrary to the standards of integrity of the sport. There is an additional offence of using insider information about an event for the purpose of betting on that event. The maximum penalty under the proposed legislation is 10 years’ imprisonment.

If this legislation is introduced, athletes, management and officials will risk jail if they do anything to corrupt the outcome of a sporting event for the purpose of betting. If other states follow suit, similar legislation will apply throughout Australia.

The proposed legislation is aimed at catching not only people who corrupt the competition outcome for the purpose of distorting a betting outcome, but also those who corrupt competition by “being reckless” as to whether that act distorts a betting outcome or not. This means that if we saw something like Vino and his Liège-Bastogne-Liège win occur in Australia, the cyclists concerned could be committing a criminal offence, even if they do not stand to benefit from any related betting outcome. And – an extreme example – if people start betting on club races in Australia, your mate who lets you win because it’s your birthday could go to jail.

It’s important to remember that this legislation, as it is currently drafted, would only apply to behaviour that is “contrary to the standards of integrity of the sport”. So long as the examples of race fixing that we have discussed here remain a normal part of racing, no law would be broken. But, as we saw in doping, what is deemed “normal” in racing can change over time. The growing pressure on sports to stamp out corrupt behaviour may cause people to re-examine what is acceptable behaviour in bike racing.

Where to from here?

The Australian government’s new national anti-corruption framework is designed to detect and prevent corruption that is betting-related. Cycling does not yet attract big betting like cricket or football, but when it does – and it is a matter of when, not if – then we can expect the instances of betting-related corruption to increase.

In the meantime, cycling faces being an unwitting casualty in the fight against corruption that is being waged by team-based sports. The regulators are drafting laws with team sports in mind – cricket, football, AFL, rugby and the like – but those laws, once enacted, will apply to all sports including bike racing. Cycling stands to be affected in a unique way because match-fixing is a normal part of race tactics. Anti-corruption legislation that is designed to restore sport to its purest form could in fact change the way our sport is raced.

Corruption is emerging as the biggest threat to the integrity of professional sport since doping. How the UCI responds to this emerging challenge will shape how cycling is raced, perceived and regulated. One thing is certain: the full extent of its impact has yet to be seen.

– By Lisa Jacobs, @LJridehappy