This year there is a total of 696 roundabouts on the route used for the Tour de France. When added to the tally of speed bumps, level crossings, median strips and road narrowings, it translates to an obstacle every 1.4km!

One of the talking points of the opening stanza of the 2021 Tour de France was safety. In the opening days, crashes created havoc in the peloton and spoiled the hopes of some of cycling’s biggest names. We begin the second phase of the race without some of the key players including last year’s runner-up Primoz Roglic, a victim of a crash in stage three.

Other riders are still in the race, but nursing injuries sustained in accidents. Ben O’Connor, for example, enjoyed a stellar ride in the rain-soaked ninth stage. He won in Tignes after a formidable day-long effort, one that elevated him to second overall after 1,447.2km of racing.

But O’Connor crashed in stage one, cut his arm in the incident, rode to the finish, and was later patched up by the Tour’s medical staff. He’s been racing with 10 stitches in his right arm.

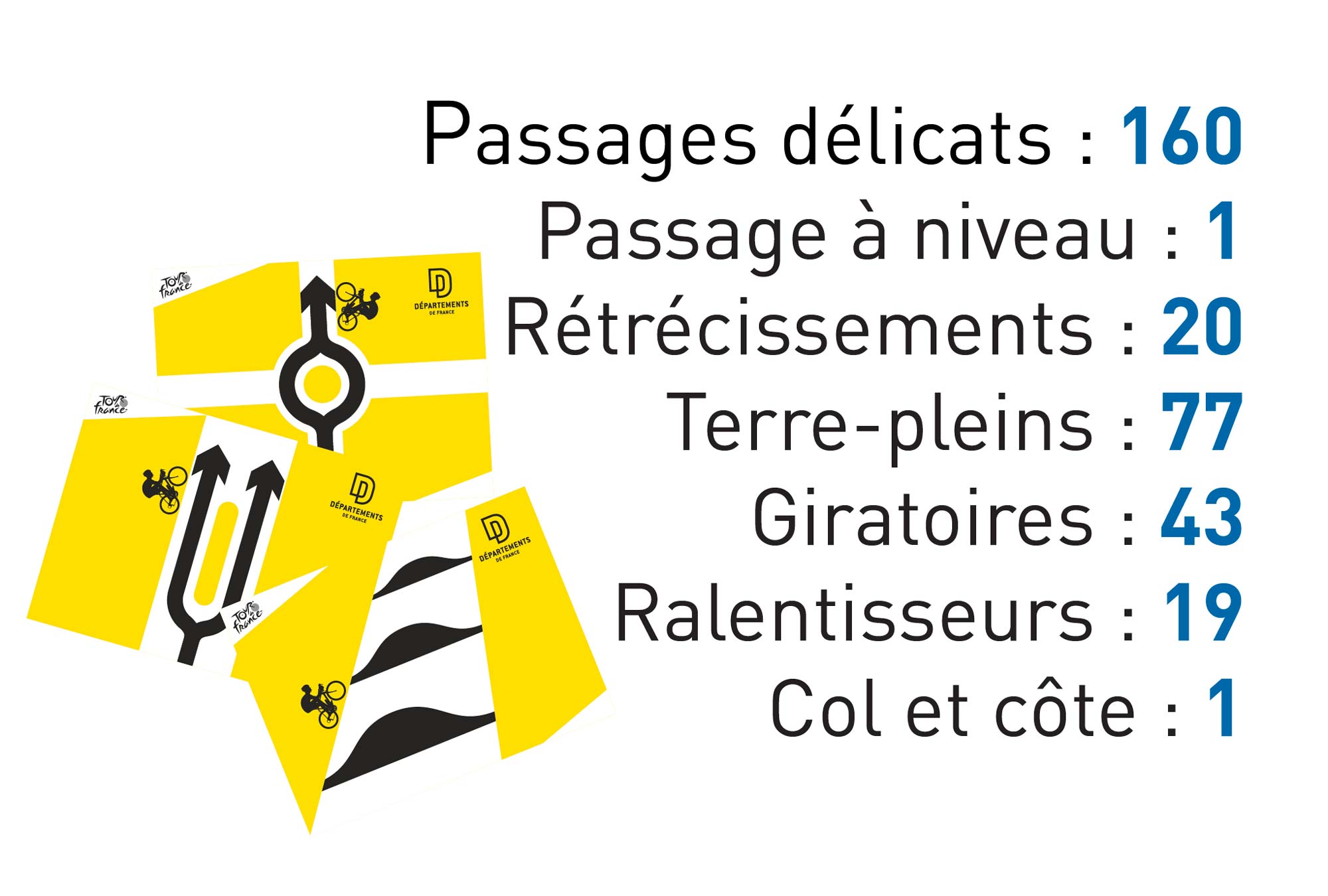

Before each stage, the department of roads provides a summary of the obstacles that are on the route. This is for stage 10 of the 2021 TDF.

Crashes are part of cycling and in recent years – certainly during the opening days of the Tour de France – they have become far more prevalent. For a sport that uses roads as its ‘stadium’, there are inherent risks.

When there are 184 riders in a peloton and the road narrows, something has to give. Either common sense prevails and riders yield to the conditions, open a gap when required and the race proceeds to the finish with everyone unscathed. The alternative isn’t always pretty: maintain position and cross your fingers in the hope that everyone makes it through the narrow passage unscathed.

You’ve seen the pictures. You know the story. You understand that there are obstacles on the road and that riders need to be vigilant or the ramification can be painful.

Crashes have ruined more than one career over the years and as long as there’s bike racing, there is the risk of falling.

In France in 2021, however, there is something else to consider: the proliferation of ‘road furniture’. The country has an obvious love affair with giratoires – roundabouts. You see them everywhere in France! And when the Tour visits the north you see even more of them… and the giratoire tally in France grows significantly year on year.

This is a story I’ve written before (for the ABC and SBS). In 2019 the choice to go left rather than right at a roundabout cost Thibaut Pinot dearly on the road to Albi. The darling of French cycling effectively went from the front of the peloton to the rear at exactly the same time there was a split in the peloton.

Pinot will never know how different things might have been had he not lost 1:40 to other GC favourites that day.

We return to the theme of road furniture in 2021 because of a number of reasons:

- The opening stanza of the 108th Tour de France was plagued by crashes.

- The race was contested largely in the north of France, where road furniture construction continues at a surprising rate.

- There is more road furniture on the route of the Tour de France than ever before!

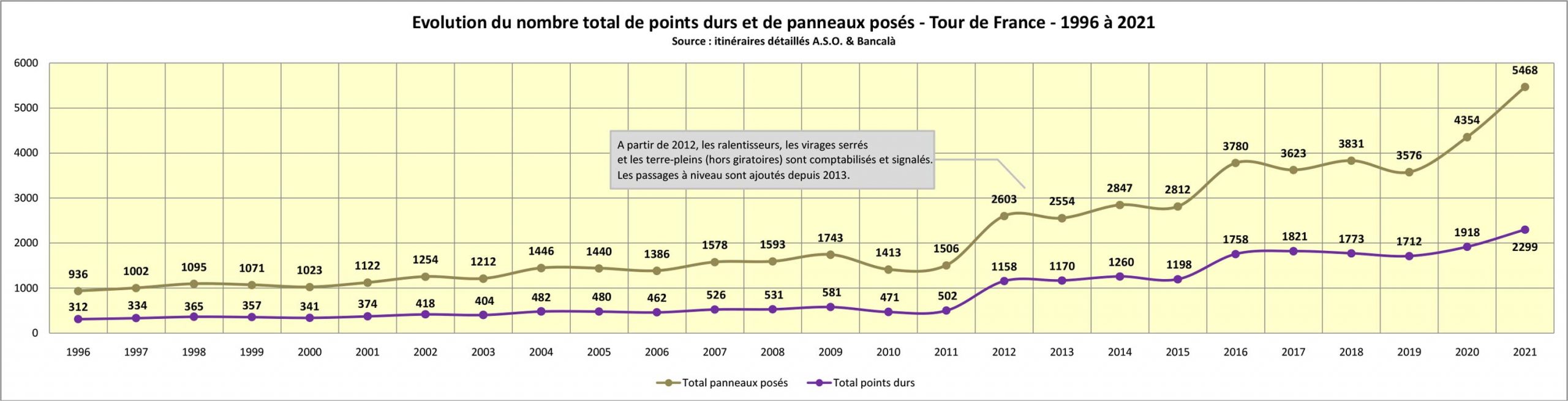

The chart below spells out the details. Over the 3,413km route of the TDF in 2021, there is a total of 2,299 obstacles for riders to negotiate. That’s approximately one item of road furniture ever 1.49km!

| Total panels installed (total panneaux posés) | 5,468 |

| Total hard points (total points durs) | 2,299 |

| Roundabouts (giratoires) | 696 |

| Narrowing (rétrécissements) | 462 |

| Tight turns (virages serrés) | 38 |

| Median strips (terre-pleins) | 627 |

| Speed bumps (ralentisseurs) | 437 |

| Level crossings (passages niveau) | 39 |

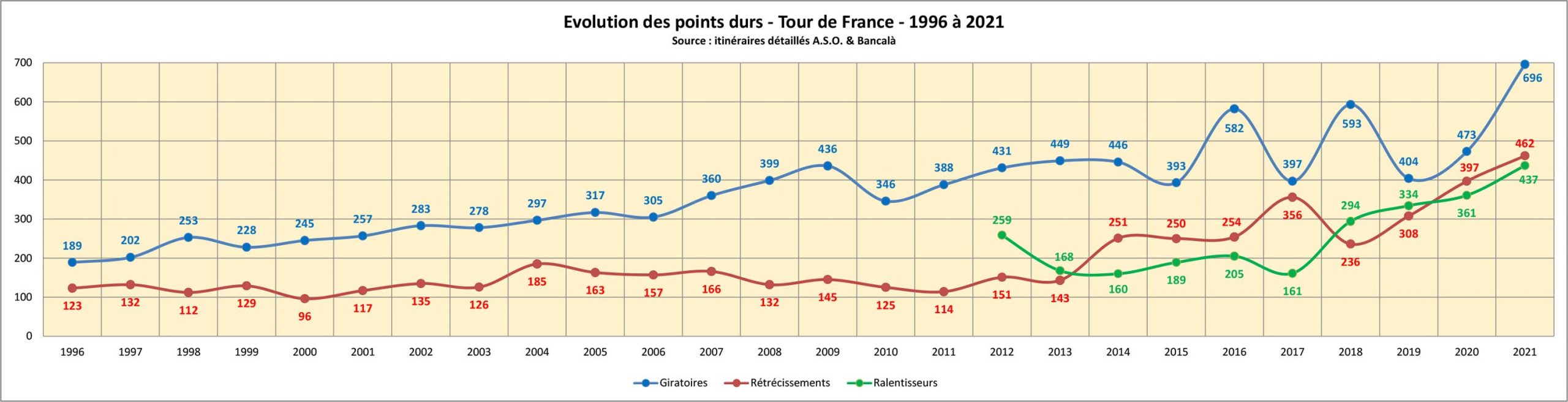

The roundabout count alone shows a dramatic increase since the last time a Tour de France was contested in front of a “full stadium” (ie. without crowd limitations imposed because of a pandemic).

In 2019, when the Tour began in Belgium and bypassed the north-west of France, there were ‘only’ 404 roundabouts on the route. (Compared with 2018, with the Grand Départ in the Vendée, when it was considerably more: 593.)

This year, there is a record tally of roundabouts; between Brest and Paris, there are 696 giratoires. It’s enough to make you dizzy.

Break it down and you realise that the peloton is passing a roundabout, on average, every 4.9km.

The organisers plan the route well in advance and yet, even between the announcement of where the race will go (in October each year) and the beginning of the Tour, there is usually an increase in the roundabout count… some estimates suggest there is one roundabout built every week in France, but it’s difficult to get accurate figures.

A count prompted by Castartelli’s death

The French department of roads works closely with ASO, organisers of the Tour de France, to limit the risk of accidents during the race. Numerous safety measures are implemented to ensure riders know what is on the road ahead; it’s no easy task and it won’t ensure there aren’t crashes but it is done with purpose – and at considerable expense.

Digital signs were introduced in 2019 to illustrate what direction riders can take when, for example, negotiating a roundabout: left side, right side, or both sides (it varies depending on the circumstance). Furthermore, corflute signs – which have long been used – also explain what road furniture obstacles are in the way.

And all these innovations have come to the Tour in the past 25 years, with the catalyst for change being the death of the 1992 Olympic road race champion Fabio Casartelli in the 1995 Tour de France.

“In 1995, Fabio Casartelli lost his life after crashing into one of the disastrous concrete parapets that ran along the side of the road on the descent of the Portet d’Aspet,” explains André Bancalà from the department of roads. “After that, there was an imperative to improve the safety of the Tour, to make it easier to negotiate the course.”

In 1996, beginning with the Grand Départ in s’Hertogenbosch in the Netherlands, the partnership between the Société du Tour de France and the Ministère de l’Equipement (Ministry of Equipment) was formalised and considerable effort was made to minimise the risks to the riders (and others travelling on the roads used for the Tour de France, including the publicity caravan).

“Protections such as wrapped straw bales were used,” explained Bancalà.

“Signs were erected for each type of roundabout and arrows highlighting the race route were installed on a daily basis in advance of the peloton’s arrival.”

The increase in 25 years has been prolific. In 1996, the first Tour since Casartelli’s death, there were only 189 roundabouts and 123 ‘narrowings’. In 2021, it’s 696 and 462!

In 1995, France had already 12,000 items of road furniture, designed to calm motoring speeds and reduce “serious accidents at intersections”. Today, their number is estimated to be between 30,000-40,000.

Bancalà recognises that this is extreme, but he also tries to joke about the French penchant for these traffic calming devises, saying how it effectively means France is the “world champion for these kinds of roads”.

It impacts the safety of the Tour, but the race only passes through sporadically. For the rest of the year the traffic calming devices serve a purpose and the dramatic drop in road accident-related deaths and injuries in France reminds us that they do work.

Crashes can spoil the festive vibe of the Tour de France and often road furniture contributes to the accidents but these have been constructed for a reason, to ensure the roads of France are safe and functional in everyday life. That’s happening… and that’s a good thing.

– By Rob Arnold