Marco Pantani provided Bianchi with plenty of publicity in 1998 but his demise really began around the time shades of pink featured on the famous celeste coloured frames from the Italian brand in 2000…

– Photos: Yuzuru Sunada

Victorious on Mont Ventoux…! After a one-year hiatus the Tour de France champion from 1998 was back in 2000 using an alumimium-framed Bianchi that featured what the company called a ‘sloping’ top tube (above). Compared to what has happened to bike design since then, you may not even notice… but, at the time, it was a significant break from tradition.

Victorious on Mont Ventoux…! After a one-year hiatus the Tour de France champion from 1998 was back in 2000 using an alumimium-framed Bianchi that featured what the company called a ‘sloping’ top tube (above). Compared to what has happened to bike design since then, you may not even notice… but, at the time, it was a significant break from tradition.

– This is an edited online version of a #RetroReview that originally published in RIDE Cycling Review #41 (September 2008) –

Arrival of the ‘compact’ frame

It started with a Taiwanese company that hired a British designer who decided to rethink the fundamentals of a racing bicycle frame.

Mike Burrows was the man behind Chris Boardman’s famous Lotus machine that he used to win pursuit gold at the 1992 Olympics, but the carbon monocoque style of construction would soon be banned by the sport’s governing body. Instead of allowing technology to take over from a rider’s athletic ability, the UCI devised rules that dictated the use of the two-triangle principle.

A bike, according to cycling’s governing body, had to look like a bike.

At the start of 1998, the biggest year of Marco Pantani’s illustrious career, a new sponsorship agreement between the Spanish squad ONCE and Giant Bicycles was taking effect. Burrows was employed to come up with something that would revolutionise the industry.

The ONCE team that Laurent Jalabert (above) raced for in 1998 was the first top-tier team to use the revolutionary TCR – Total Compact Road – frame by the Taiwanese manufacturer, Giant. Until 1998, the top tube of road bikes generally were designed to be parallel with the ground.

The resulting “compact” frame design marked a new era for the bike. This had nothing to do with the rider who would go on to win the Giro d’Italia and the Tour de France that year. But ‘il Pirata’ would become the first to claim cycling’s most prestigious prizes using a frame that adhered to the same concepts that were so widely derided on debut.

Bianchi’s XL EV2 aluminium frame was tweaked a little in the years between Pantani’s victories in the 1998 Giro and Tour de France, and when he used the featured bike during clashes with Lance Armstrong in 2000 but the main elements remained.

Although the slope of the top tube on Pantani’s Bianchi is not as severe as the Burrows-designed Giant ridden by Laurent Jalabert and his ONCE team-mates in 1998, the black, celeste and pink bike is essentially the same as what Pantani used during his most celebrated years with Bianchi.

Cane Creek supplied Bianchi with an integrated headset for Pantani’s bike from 2000. This was the period when 1-and-1/8th inch fork steerers became the norm, and traditional quill stems became largely redundant.

Pantani had become the company’s pin-up rider; catalogues were based on his image and achievements. And it wasn’t Bianchi alone that thrived on the impact this climbing sensation was having.

Campagnolo also plastered promotional material with photos of the rider… At the time Pantani was king.

Before he had his ears pinned back with plastic surgery, and while he wore diamonds in an earring that enhanced the image of his nickname, the pirate of the slopes was a marketing team’s dream.

It wouldn’t last long but, in his heyday Pantani was part of numerous campaigns that generated a want factor for products. It was before ‘Lance-alot’ began to commercialise cycling on a scale that previously had never been thought possible, and the Italian influence helped add authenticity.

Curiously, it also gave credibility to a concept that was widely decreed as “ugly” when first released.

There’s no second-pass welding on this bike! The bead of the weld is neat but chunky. It was common, for aluminium frames in the 1990s, for manufacturers to smooth out the junction by running the welding torch over after the initial join has been made…

The early incarnation of the design Burrows had drafted for Giant was based on making quality bikes more accessible to the masses.

The first Total Compact Road (TCR) release had just three size options: adjustments, so the thinking was, could be made via three adjustable stem lengths and a range of seven aero shaped carbon seatposts.

Like many other manufacturers, Bianchi initially wanted no part in this ‘compact revolution’.

The Italian brand had its heritage to protect and a frame with a sloping tube just didn’t suit the aesthetics of a company that had been making bikes for 113 years already. For most of that time its creations featured beautifully crafted steel; it was what Bianchi had built its reputation on.

The first generation 10-speed ensemble from Campagnolo made its appearance in 2000. Pantani used 170mm cranks and a 53/39 chainwheel ratio.

Bianchi began sponsoring the Mercatone-Uno squad in 1998. The Reparto Corsa catalogue that year featured mainly steel frames although aluminium also got a mention.

“New technical solutions are first tested in races then used in mass production,” read the text of Bianchi’s 1998 brochure. It was a reference to “Mega X Pro Al”, tubing developed in conjunction with a Californian-based research centre. It seemed to fit the modern connotations the marketing department sought.

Hyperbole was rife. The new material was said to have been “the vanguard in the application of the most recent bicycle building techniques.”

After years of denial it was time to capitulate. There had been experimentation with titanium when Bianchi supplied bikes to the infamous Gewiss-Ballan team in 1995 and 1996. In 1997 the Russian-registered Roslotto-ZG squad was riding celeste coloured frames built of ever-reliable steel. It would be the last season the company used this material to fulfil its pro team sponsorship arrangements.

Bianchi supplied bikes for the controversial Gewiss teams of the 1995 and 1996 season, including this TT bike for Evgeny Berzin which… ah, took the sloping top tube to an entirely new (thankfully unrepeated) level. (Photo: Graham Watson)

With Pantani on the payroll, the company was given the catalyst to alter its approach.

He had been an ambassador for another Italian brand, Wilier, the previous season when he set the record time for an ascent of L’Alpe d’Huez and such antics had earned him a cult following.

Pantani could help reinvigorate the reputation of a brand that had been losing its market share to aggressive companies from the United States and Asia.

Campagnolo’s brake/shifting levers changed very little in the decade that followed Pantani’s halcyon years. Carbon was introduced in 1999 to replace the aluminium lever originally used.

Thus the Mega Pro concept was unveiled in mid-1998. The frame was “characterised by specific shapes and forms, especially in the down tube, that give the frame the ideal equilibrium between aerodynamics, absorption of forces and transfer of power”. Isn’t that what they all say? Roughly.

These days it’s how the carbon is laid up that prompts the desirable ride qualities. Back in Pantani’s day it was apparently achieved by the teardrop shape that reached its “maximum dimensions at a point 20cm above the bottom bracket. Here it then changes again to arrive at the [BB shell] with a distinctly elliptical form.”

Bianchi wasn’t shy about purporting the benefits that could be gained from the new shape of the 7000-series aluminium tubing. Other developments – such as structural form injection – were also referenced in detail inside the brochures.

Interestingly, only passing reference was made to the other major alteration from their previous designs: the “sloping” top tube.

It was subtle, far less exaggerated than what Giant wanted ONCE to use, but it signalled an acceptance that Burrows’ design had some merit. Bianchi’s top tube was no longer parallel to the ground; it tilted downwards from front to rear with a “light sloping geometry” of just three per cent.

The bike used by Marco Pantani when he won the Tour de France in 1998 (above) was made with aluminium tubing, the last time an alloy frame won the world’s biggest bike race.

There’s still much conjecture about the notion. Are real benefits achieved by reducing the size of the two triangles, thus creating a “compact” frame, or is it just a perception?

Some suggest it’s lighter because less material is needed, others argue that the need for an extended seatpost negates that. Some believe that it creates a more rigid frame. Many now say it’s a better aesthetic while traditionalists scoff at that notion.

One thing is certain: the three-sizes-fit-all approach lasted only a matter of months. Giant recognised that, to get a bike to fit the rider properly, additional options were required. So the Taiwanese continued with the compact concept, only with more sizes in their ever-expanding range.

By the time Marco Pantani returned to the peloton after having been booted out of the 1999 Giro d’Italia on the eve of what seemed would be a certain second victory, Bianchi had taken the compact principle and embraced it. Not only did the company offer alloy frames akin to what Mercatone Uno used, it also sold titanium models with a sloping top tube. The range even included Ti frames with (abbreviated) carbon rearstays!

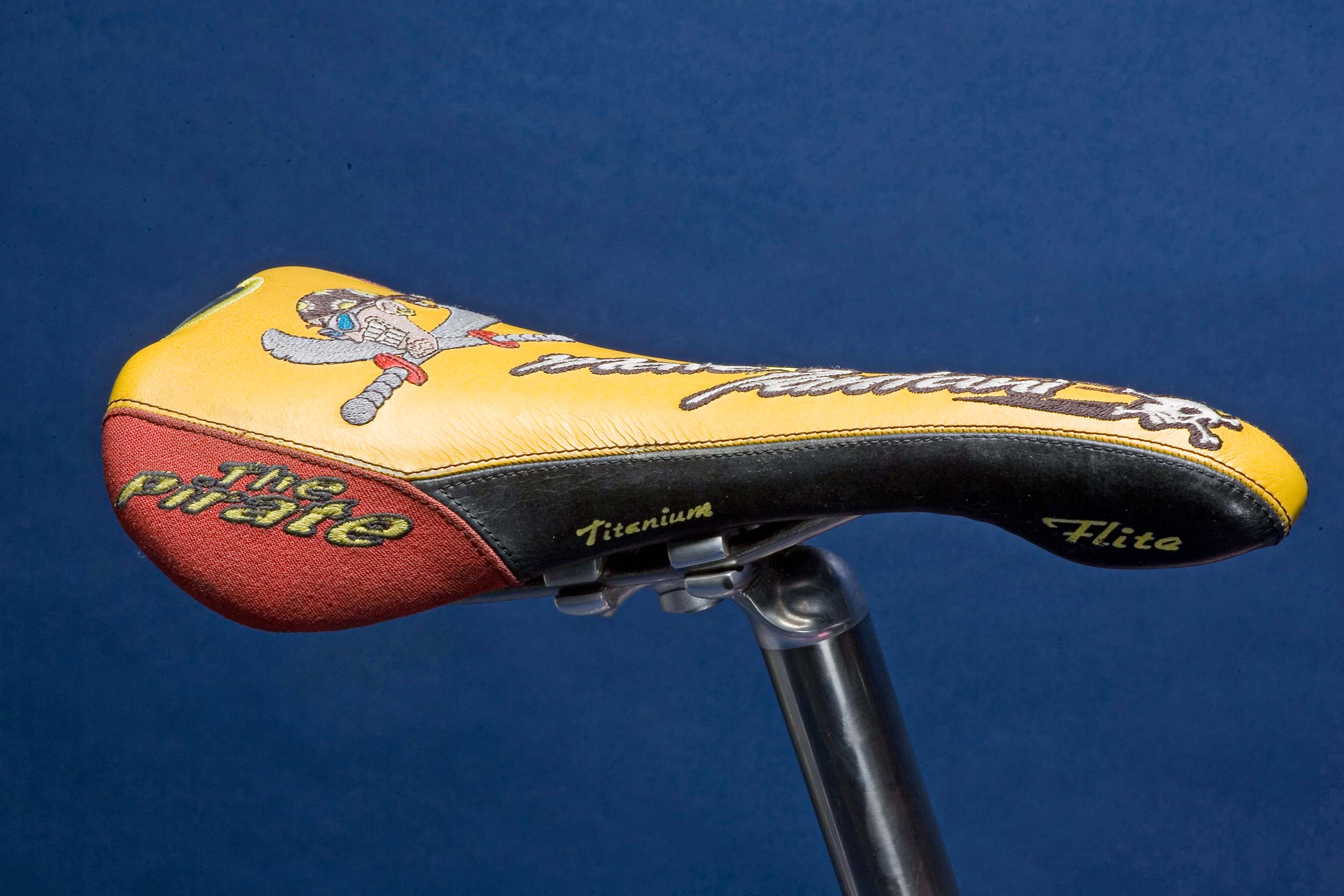

The Flite saddle must have provided plenty of comfort even with all its embroidery. But the stitching would likely have been felt a little more by Marco Pantani than other riders… why? Well, in the later years of his career he often raced without a chamois.

The ugly duckling retained the same aesthetic as when introduced a few years earlier, only by 2000 even the cynical companies that originally mocked it believed the design elegant enough to be part of their high-end releases.

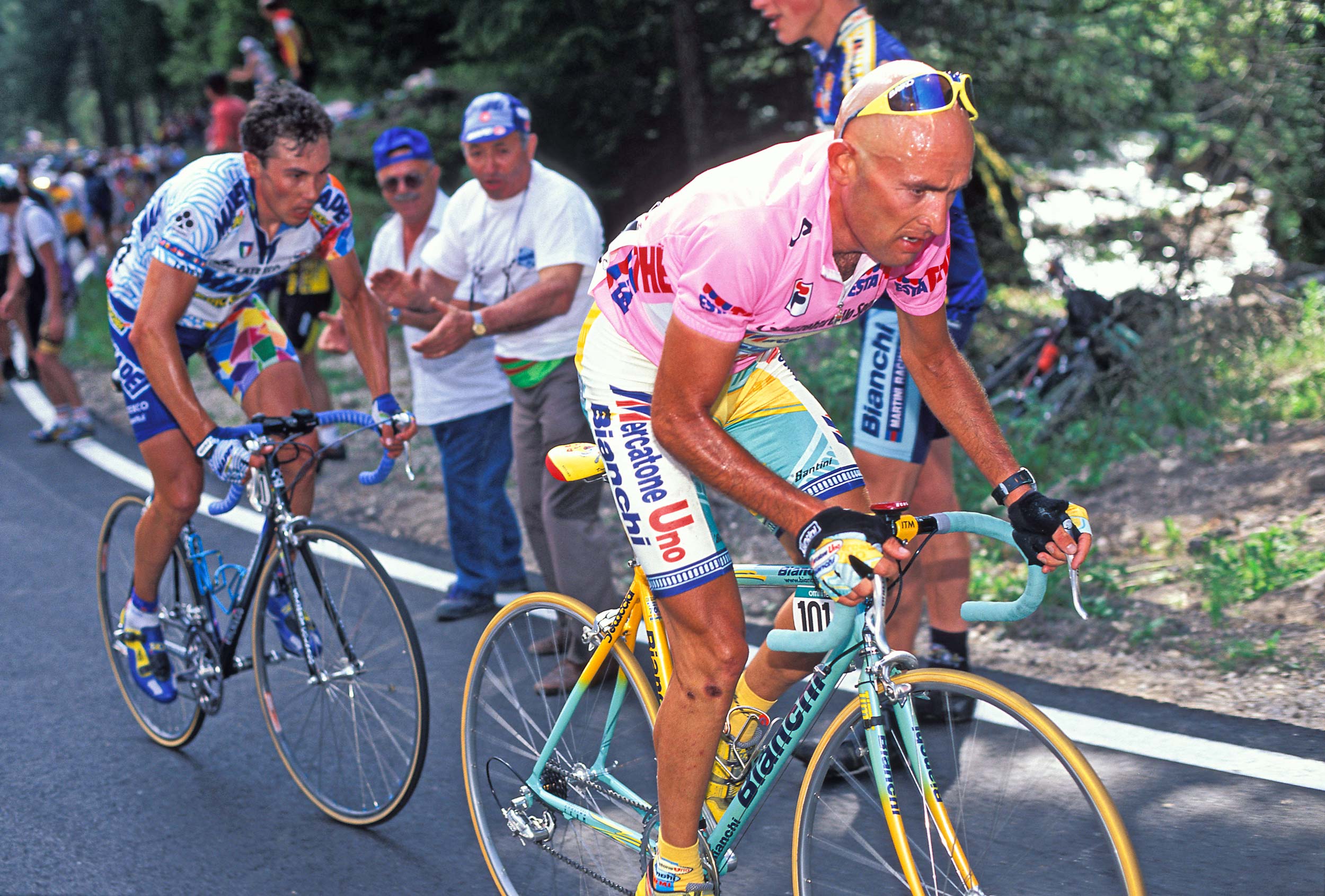

From 1998 to 2000 Pantani’s bikes were refined slightly but the main change during that time was the colour scheme. When he won the Giro he was aboard a celeste frame with hints of yellow.

For Bianchi and Mercatone Uno it was the perfect compromise: the corporate hues of both entities were represented and it transferred well to the cycling scene. Yellow represented the naming-rights sponsor and also held significance for the next race il Pirata was to contest.

When he climbed into the maillot jaune, it all seemed predestined.

Pantani’s bikes are now on display in a museum in Cesenatico, Italy.

Marco Pantani lined up for the 1999 Giro d’Italia as defending champion. His team-mates used bikes painted in the same colours as the year before while their captain was issued one that substituted black where celeste had been.

It was an ominous sign of the dark days that lay ahead even though the race got off to a bright start for the Italian star.

He was beaten into third place by Jalabert in stage five at Monte Sirino. Three days later he covered the 253km eighth stage – over three mountain passes – in just over seven hours, finishing 23 seconds ahead of José Maria Jiminez.

Pantani was back in the maglia rosa but he would soon surrender it, first to Jalabert for a few days and then to the carabinieri who escorted him from his hotel after his haematocrit level surpassed the legal limit.

This positive control effectively marked the beginning of the end of Pantani, even if there were still some moments in the spotlight remaining in his cycling career.

After his Giro expulsion in 1999, the rules stipulated that he had to “rest” for 14 days before competing again.

In theory, he could have gone to the Tour de France to defend his title but it was all too much. He skipped a year and returned to the race, using the featured bike, in 2000.

Pantani leads Pavel Tonkov in the Giro d’Italia of 1998.

Throughout the trauma and protestations of innocence, Bianchi stood by the rider who had helped reignite interest in the brand with a few years during the prime of his racing career.

When he did return to the Tour in 2000 he was still on a Bianchi and riding for Mercatone Uno. At the request of the race organisers, the team swapped its usual yellow kit for pink to avoid the risk of confusing it with the leader’s jersey. And so the colours of the squad leader’s bike also changed again.

Places that were yellow on the 1999 Giro frame were repainted pink.

The carbon Time forks used in 1998 were replaced by a Bianchi-branded option but the base remained the same. By this time other changes to bikes used by the professionals were more common. Lance Armstrong had replaced the quill stem he used in 1999 with one using the Aheadset arrangement, thus relegating the old method to history. Quill stems have never been seen again at that level of competition.

Campagnolo introduced carbon into its component line-up during Pantani’s Bianchi years. The Ergolevers switched from aluminium to composite at the start of 1999 and before long the beautiful titanium post would also be retired in favour of the material that now dominates cycling products. The Italian parts manufacturer used the rider to launch its 10-speed Record ensemble essentially to stay on par with Shimano.

A lot has transpired since his years at the top. The champion died a lonely death in February 2004 with the autopsy report citing acute cocaine poisoning. He still had a pro contract but his association with Bianchi ended after 2001 and the true desire to compete had long since faded.

– By Rob Arnold