– Words by Giulia Lacivita.

– Photos: Antonio Bigarini.

The phone rings. A woman answers.

“Idrio, they want to talk to you… Idrio? Hey Idrio…!”

Then, in the background, a voice with a pronounced accent from Tuscany says:

“Tell ’em to call later! I am watching the TV. The races are on…”

When “the races” were over I managed to get in touch with Idrio.

Sinalunga is a small and modest village at the borders of the Chianti area, down in the green valleys. Small houses, churches, bars, fields. Not much more. “I live close to the Coop supermarket, you’ll find my house.”

Coop in Tuscany is the main supermarket to which local food producers and local farms sell the food directly. Not just another supermarket, but the supermarket. I’m directed to a vague description of a location, no exact address. Whatever. When I was “close to the Coop supermarket” I noticed that the houses were small, all but one. I slowed my car down. A woman was looking outside while cleaning the terrace. We looked at each other; she smiled and asked, “Did you get lost? Come over!”

Of course I looked like a stranger. Everyone knows each other in such a small village. I accept the offer and shortly afterwards, Idrio began to talk.

“Mine is a story about men and bicycles. Mine is a beautiful and ancient story. A long story, which began when I was only 15 years old, and I started racing using a women’s bicycle. At that time I couldn’t afford to buy one, bikes were too expensive and my family was not rich at all. The only way for me to race was using my mother’s bike. That’s how everything began. Thanks to her.

“Only one year later, in 1948, with the savings I had I managed to buy my first bike. Every morning I used to go to work to the Poggi Gialli furnace factory. Every early morning cycling 15 miles to work, this was what my father wanted me to do, make money and bring it home. ‘When you have seven sons you have seven mouths to feed,’ he used to tell me. ‘Don’t forget this Idrio.’

“But then, day after day, cycling became a passion and not only a necessity, not only a means to reach my job.

“That’s how I started. Friends started encouraging me to race. I started believing in myself, in my legs and in my dreams. I gained good positions in the early contests too.

“This was the beginning of my career.”

It was 1949 when Idrio Bui began to race. The year of the famous ‘Tour of Wonders’, so it was called, the 32nd Giro d’Italia. And while Idrio Bui was becoming a student, Fausto Coppi was winning the title of the Italian race. In the meantime someone else in Tuscany, close to Florence, was accepting defeat: Gino Bartali had to admit Fausto was becoming the campionissimo.

In those days, post-war Italy was strongly divided in politics and would remain so for more than 40 years.

The longstanding fight between the socialist Fronte Democratico Popolare party and the Catholic, anti-socialist Democrazia Cristiana had just begun. The split was reflected in the sporting world.

While Bartali was known as a man of Catholic beliefs, Coppi was close to the socialist ideals.

This was the melodramatic opera distraction the public needed after a war, a rotten conflict which had destroyed not only cities but also hopes. While the press was already portraying the romance, in the 1949 Tour de France photographers were taking shots of what today is the most iconic moment of Italian cycling: Coppi and Bartali on the steep slopes of the Pyrenees sharing a bottle of water.

But who is passing the bottle to whom?

“There are two different shots, you have to know this. In both of them Coppi is in front,” says Idrio.

“In the first one a tifoso gives Coppi a bottle, probably a Perrier bottle. Coppi, after having been refreshed, passes the bottle to Bartali. In the second and most famous one taken 1952 by Carlo Martini, Bartali is the one who passes the bottle to Coppi! I know this for sure. As a racer Bartali told me this… Coppi had the yellow jersey that year, who would you think would have passed the bottle to whom?”

However, after Coppi’s death, Bartali had never declared anything about that, always laughing and answering journalists ironically and mysteriously. There are even rumours that the 1952 drinking scene was set up. Others argue that the person who gave the two riders water at the feeding point was a woman, which adds even more emphasis to this great and melodramatic opera plot.

Unfortunately no one will ever know how things really went, but that’s not important. What matters is just that romance was there, and so it is still nowadays.

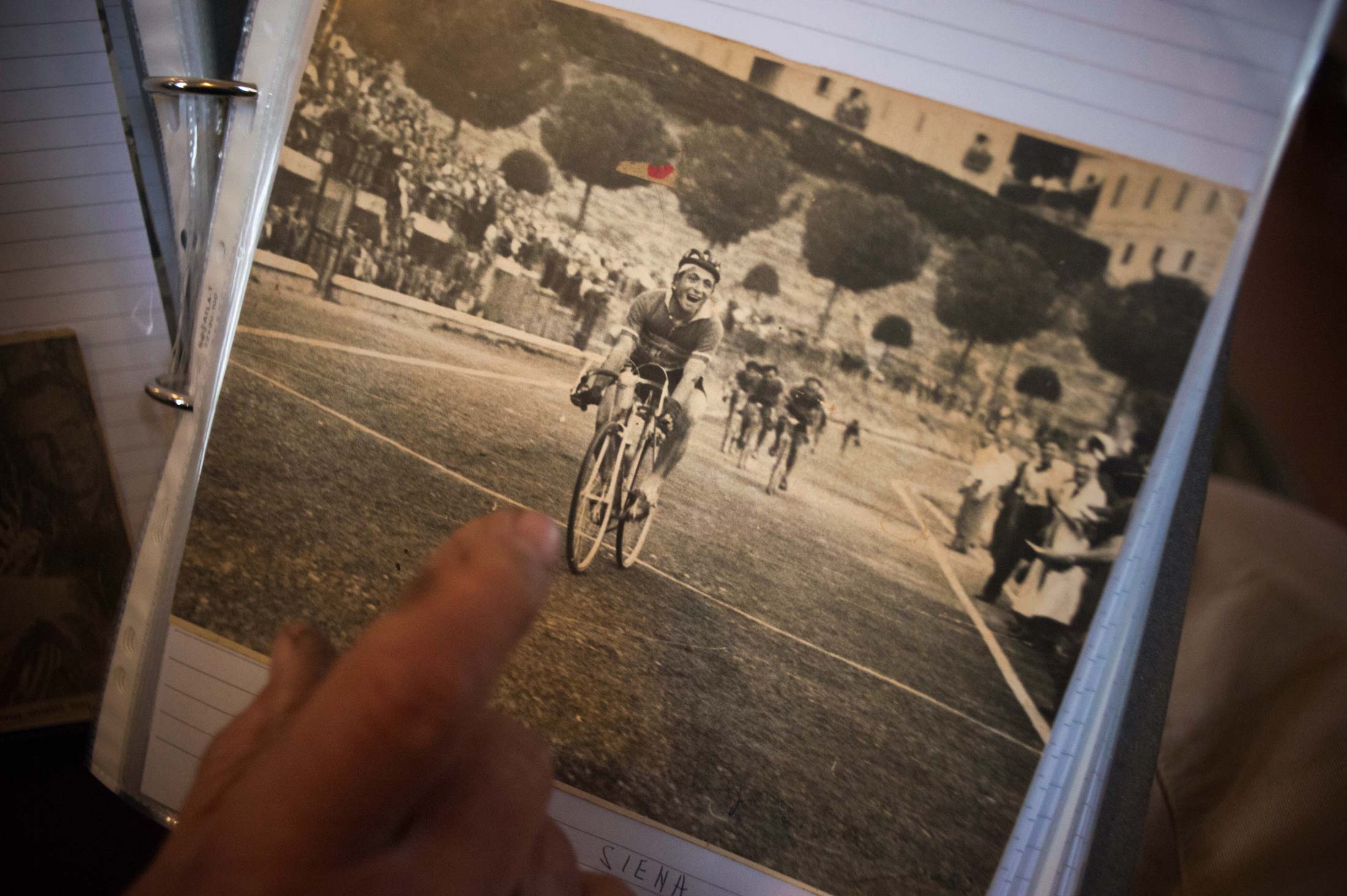

In the meantime, in 1949 Bui earned his first victory in a junior race in Gaiole in Chianti in Tuscany. Laden with awards, Idrio went back to work the next day.

“For me it’s all about working and cycling. And I can even win,” he said the next morning to a journalist who was waiting for him next to the big fence in front of the Poggi Gialli factory.

Like many other riders of the time, Idrio started out of necessity. He belonged to the peasants and factory workers side of his country. When the first successes came, pedalling was transforming more and more into passion and hope. For Idrio, the need to ride was about to become a choice.

His great opportunity came in 1950, when Idrio’s sister was fired from the furnace factory. It was enough for Idrio to ask to be sacked instead. This was a real turning point in his life.

His dream became reality with the well-deserved entry into the amateur category. Training sessions were intensified and victories increased.

“In Sinalunga everyone helped me and sent me to win. I remember friends collecting money to pay for my travel expenses when I had to race far away, since money wasn’t there yet.”

The choice is tough when you come from a poor and large family. It is true that one could get by with a bicycle, but it is also true that to do that one has to make a career, increase performances day after day. But furthermore it’s essential to believe in your legs and in yourself.

For Idrio, at the end of the day, it was a matter of an appetite for risk. A real bet for him and for his family. Running with a broken arm, then, was the least that an aspiring professional like Bui could do to reach that goal.

“It was 1951. It was only one year after I had left my job to try and start racing as a professional. My dream began. Early in the season I fell and broke an arm. I thought it was all over. I remember that, the next day, I was on my bike again, training as if nothing had happened. In the following two years, I reached 56 victories as an amateur.”

It was cycling on the white roads of Tuscany.

It was cycling in the Italy of the 1950s.

On these roads, mostly Vespas and bicycles were to be found.

From time to time a Fiat 500 or an Alfa Romeo Giulia was raising dust for the ‘joy’ of cyclists. It was the Italy of Coppi at the age of 33, Bartali around 40, Fiorenzo Magni in a great shape and Nino De Filippis trying to stand out among the big ones.

At that time the Giro was still contested at an average of around 22 miles per hour. The distance of such a race was ±3,000 miles and most roads were still without asphalt. This was the cycling world where Idrio had to emerge. For a young man born and raised in the Chianti Val di Chiana area, an enchanted valley paved with roads that accompany the ridges of hills, the slopes were not a problem at all. Race after race, Idrio Bui drew the attention of experts in the cycling panorama of the time for his aggressive style that made him excel at climbing as well as being formidable on the flats.

The young athlete from Sinalunga became classed among the best amateurs in Tuscany.

Suddenly a radical change took place. The times when only the press followed the Giro were gone. At that time La Gazzetta dello Sport was to be found in the sport press for five lira and was only published three times per week. Until then, the news was tied exclusively to the paper.

On 3 January 1954 public service television in Italy began. It was a revolution for cycling and sport in general. Seven stage finishes were transmitted live; other stages were recorded and aired in the evening.

The austere world of cycling had always been reserved for men.

Now women also started to burst onto the scene.

The heroes of cycling are transformed into stars, feeding the papers with images of enthusiastic fans.

Secret love stories thrilled the media and Jacques Goddet, the Tour de France director, ended up forbidding the presence of women at his race. And then the scandal – something that shocked the whole post-war Italian bigotry. Fausto Coppi and Giulia Occhini, the so-called Dama Bianca. An awkward love, outrageous and, as Bui says, perhaps unfortunate.

“I was 16 years old when I met the girl who now is my wife,” tells Bui.

“In her I found a woman who respected me as a man and as an athlete. Cycling is the sport of sacrifice and you have to train hard every day. It’s not like soccer, you know; in soccer if you’re tired you just pass the ball or ask to be substituted, in cycling you can’t… That’s what it is all about.

“For Coppi, however, it was not like this. I remember the image of his wife, Giulia Occhini, complaining about the delay when Fausto came back home after a workout. Despite my big respect for Fausto I have always been sceptical about their relationship. But at the end of the day even the bigs have to deal with their wives…”

Bartali stopped racing when he was more than 40, becoming a businessman soon after. And while Coppi was having his first son Faustino with Giulia, Idrio’s glory was getting closer. But still, the long-awaited professional contract was something for which Idrio had to fight.

The disappointment and anger exploded in 1956 when the athlete found himself unjustly excluded from the team representing Tuscany. Idrio was expelled and forced to continue as ‘independent’: this was the price he had to pay after a strong argument with the leadership of the team.

“I don’t remember much of that day,” he confesses.

“I remember I was furious… I mean, I deserved to be on the team and God only knows how many sacrifices me and my family had made for that. I could feel the responsibility towards my father for having chosen this career and not being successful in it. I only remember a great room, a long table, me on one side, the Tuscany team director and its staff on the other, me swearing and shouting. But the straw that broke the camel’s back was when I told ’em, ‘Everyone thinks the Mafia is in Sicily, but it’s not. The Mafia is here my friends. The Mafia is in this organisation.’ Within two minutes I was outside the room.

“As an independent I had to pay all the expenses myself. Starting everything from the beginning; it was something I could not accept. It was 1957 and I was 25. I decided to quit. I announced to my family that my last race would be the upcoming Giro dell’Appennino in Tuscany, where at least I did not have to pay much to travel to.”

Italy grew and the “economic miracle” was near. Cycling was the sport, Fausto Coppi the man. Though his legs were not as invincible as in the good old days, the campionissimo was still deciding the sport’s fortune or failure. And, with that, the other cyclists’ lives too.

“I could not imagine my future was in his hands… I could only see myself working again at the furnaces. I was exhausted.”

After only 20km of Giro dell’Appennino, close to Passo Giovi, Idrio was in the lead when his chain came off the front derailleur. Separated from the group, he managed to cross the finish line in 30th position. Another disappointment.

“After the race I was washing at the fountain and I remember I saw a guy coming towards me. It was Ettore Milano, the most faithful gregario the campionissimo had. He invited me to the Hotel Excelsior, because ‘His Majesty’ Fausto Coppi wanted to talk to me. I climbed back on the bike and raced towards the hotel. I found him lying while he was having a massage. Not too many words. He explained to me he was looking for riders for the coming year’s new team. He proposed a monthly 40,000 lire contract. I signed immediately. I couldn’t believe it!”

On one side, Coppi, the undisputed campionissimo at the end of his career. On the other, the young Idrio Bui who was about to realise his dream. It was the chance to become a “class A gregario”, the gregario for a champion.

“I raced as a professional from 1957 to 1964. Three years with Coppi and his team, then I had the honour of working for many other champions like Baldini, Nencini, Poblet. As a professional my job was to help the champions to win. I was always close to them, gave them supplies and, if necessary, even pushed their bikes. I never spared myself.”

Idrio had made the right choice. During those years he always raced at his best, doing more than a good job and also collecting some victories for himself. He never became a great champion, not one of those haunted by photographers, but he had more than he had hoped for, racing as a professional next to the most respected Italian cycling champion of all time, Fausto Coppi.

One might argue that the life of a gregario is far from easy. Always in the shadow of the great champions, always ready to give everything, always a few steps from the finish line and from the victory but paradoxically more distant than before. Because being a gregario means never being able to emerge against the wishes of the captain. It means sweating, pedalling like crazy, but after having finished this task, it means stepping aside and disappearing into the group. I have always imagined the life of a gregario like that.

Listening to Idrio, it seems I have missed something. What Bui has told me and what he speaks about is the poetry of the gregario. Sweat and toil for which they do not need an award to be commended. Generosity and altruism in the uphills, indeed, especially there. Perhaps people in the first place and then athletes. Devotion, lots of devotion.

“I remember how much I was suffering when trying to help Fausto. In those moments my only friend was the Virgin Mary icon in the gold chain I had around my neck. I used to bite it asking her for the strength.”

On the other hand, if you think about it, spotlight and flashes are only at the end but for most of the race, the champion is just in the shadow of his gregario.

“Day after day, race after race, I felt I owed Fausto something. I had to help him in any single race. I had to make him win as much as possible, I had to give him a reward: he had already made me win my most important race, the race of my life.”

– By Giulia Lacivita